In this excerpt from My Country My Life, Advani recounts meeting Vajpayee in 1952, and the next 50 years of their unprecedented political partnership.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee: A statesman with a poetic soul

A Tribute to Atal Bihari Vajpayee

‘Haar nahin manoonga, Raar nayi thanoonga, Kaal ke kapaal par likhata-mitaata hoon, Geet naya gaata hoon.’

(I shall never accept defeat; Ever shall I get ready for a new battle; I am he who erases old things and writes new things on the forehead of Time; I sing a new song)

—ATAL BIHARI VAJPAYEE

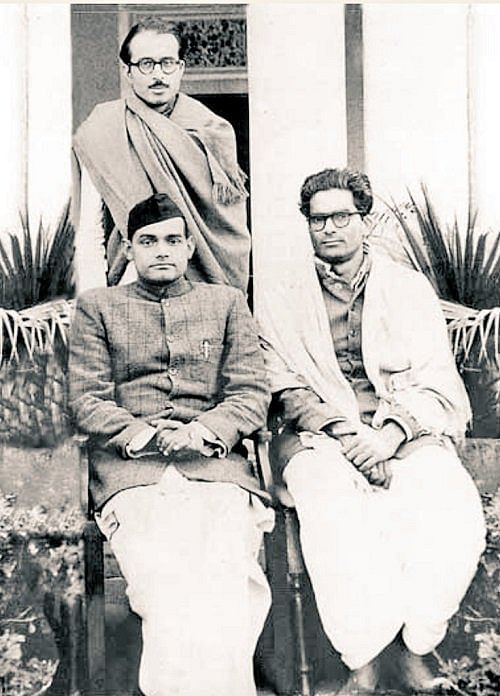

If I have to single out one person who has been an integral part of my political life almost from its inception till now, one who has remained my close ally in the party for well over fifty years, and whose leadership I have always unhesitatingly accepted, it would be Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Many political observers have noted that it is not only rare but, indeed, unparalleled in independent India’s political history for two political personalities to have worked together in the same organisation for so long and with such a strong spirit of partnership. In the Prologue to this book, I have referred to a photograph of Atalji, Bhairon Singh Shekhawat and myself, taken in Rajasthan in 1952. It was reproduced by a Hindi daily, along with a similar-looking photograph of the three of us in 2003, with a common caption: ‘Working Together, For Over A Half-Century’. I regard this long comradeship with Atalji a proud and invaluable treasure of my political life.

First impression, last impression

I first met Atalji in late 1952. As a young activist of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, he was passing through Kota in Rajasthan, where I was a pracharak of the RSS. He was accompanying Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee on a train journey to popularise the newly formed party. Atalji was Dr Mookerjee’s Political Secretary those days. Looking back, the image I recall most vividly is that of a young and intense-looking political activist, nearly as lean as myself, although I looked leaner because I was taller. I could easily tell that he was imbued with youthful idealism and carried around him the aura of a poet who had drifted into politics. Something was smouldering within him, and the fire in his belly produced an unmistakable glow on his face. He was twenty-seven or twenty-eight years old then. At the end of this first tour, I said to myself that here was an extraordinary young man, and I must get to know him.

Atalji became the Founder-Editor of Panchajanya, a nationalist weekly in 1948, and as its regular reader, I was already familiar with his name. Indeed, I had been much influenced by his powerful editorials and some of his poems that the journal published from time to time. The journal was also my introduction to the thoughts of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya, who had launched it in Lucknow under the auspices of Rashtradharma Prakashan, a publisher of nationalist literature. I later learnt that, along with Atalji, he used to perform multiple roles in the weekly: a regular contributor who wrote under many pseudonyms, proofreader, compositor, binder and manager. For someone like me, who had recently learnt Hindi, Panchajanya was a useful introduction to the innate beauty and purity of the language, as also to its immense capacity to convey patriotic inspiration.

Also read: Atal Bihari Vajpayee: Poet-politician and one of India’s most charismatic leaders

Sometime later, Atalji came alone on a political tour of Rajasthan and I accompanied him throughout his journey. It was during this trip that I got to know him better, my second impression about him reinforcing the first. His remarkable personality, his outstanding oratory whereby he could hold tens of thousands of people literally spellbound, his inimitable command over Hindi, and his ability to effectively articulate even serious political issues with wit and humour — all these traits made a deep impact on me. At the end of this second tour, I felt that he was a man of destiny, a leader who deserved to lead India some day.

Fellow-travellers on the long political journey

That was a time when, after Dr Mookerjee, the person who mattered the most in the Jana Sangh was Deendayalji. He too thought highly of Atalji and gave him greater responsibility in the party and Parliament after Dr Mookerjee’s tragic demise in May 1953. Within a short time, Atalji established himself as the most charismatic leader of the party. Although the Jana Sangh was only a young sapling before a giant tree called the Congress, people thronged to listen to Atalji’s speeches, even in places where the party had no roots. Besides his oratory, they were also impressed by the alternative perspective he provided on national issues that distinguished our party from the Congress and the Communists. He thus showed, at a very young age, all signs of emerging as a mass leader with a nationwide appeal.

After Atalji was elected to Parliament in 1957, Deendayalji made another move — one concerning me. Deendayalji asked me to relocate from Rajasthan to Delhi and assist Atalji in his parliamentary work. Ever since then, Atalji and I have worked together in every phase of the evolution of the Jana Sangh and, later, the BJP. Soon after entering the Lok Sabha, he became the voice of the party in Parliament, commanding a reputation far in excess of its numerical presence. A decade later, after the tragic death of Deendayalji in February 1968, he also had to carry the responsibility of party Presidentship. It was an extremely difficult period in the party’s history, but Atalji soon emerged as a capable leader, steering the Jana Sangh out of the deep morass. That was when the slogan Andhere mein ek chingaari Atal Bihari Atal Bihari (Atal Bihari is the ray of hope in this pervasive darkness) became widely popular with the workers and supporters of our party.

Five years later, in 1973, he entrusted the party’s organisational responsibility to me. The camaraderie that I enjoyed with Atalji, Nanaji Deshmukh, Kushabhau Thakre, Sundar Singh Bhandari and others while building the party together remains a deeply cherished part of my political journey. By the time Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency in June 1975, the Jana Sangh had already earned the reputation of the strongest and most organised Opposition party. No wonder, it also earned the trust and confidence of Jayaprakash Narayan, and became the most spirited contingent of the phalanx of pro-democracy fighters that he mobilised on a common platform. Once again, Atalji and I fought together, went to prison together and, after the Emergency was lifted, worked together towards the formation of the Janata Party. Indeed, after JP’s health started to deteriorate (he passed away on 8 October 1979), no two persons worked harder and with greater conviction than Atalji and I for the cohesion of the Janata Party and the stability of its government.

Paradoxically, the price we paid for our effort to preserve the Janata Party’s unity was that we were expelled from the party on the specious ‘dual-member issue’. Once again, along with other colleagues, I worked with Atalji in founding the BJP in 1980. True, the party’s debut performance in the 1984 Lok Sabha elections was dismal — we won only two seats. Even Atalji was defeated in Gwalior. However, this was entirely due to the extraordinary situation created by the assassination of Indira Gandhi. It wasn’t really a Lok Sabha poll; it was rather a ‘Shok Sabha’ (condolence) poll, where the sympathies were bound to be with the bereaved.

The BJP’s subsequent trajectory of meteoric growth was due to the Ayodhya movement. It was the time when Atalji chose to remain relatively inactive. However, I have never had any doubt — that the party’s journey from failure to form a stable government at the Centre in 1996 (when Atalji was Prime Minister for only thirteen days) to the success of doing so again in 1998, was mainly due to his personal popularity that transcended the party’s support base. Once again, we both worked closely together to forge the NDA, breaking the shackles of political ‘untouchability’ that the Congress and the Communists had tried to create.

For a long time after I launched the Ram Rath Yatra in 1990, to mobilise support for the Ayodhya movement, a peculiar asymmetry arose in the media’s projection of Atalji and me. Whereas Atalji was seen as a liberal, I was labelled as a ‘Hindu hardliner’. It hurt me initially, as I knew that the reality was entirely contrary to the image that I had come to acquire. Conveying this feeling to friends in the media was an uphill task and it was then that some colleagues in my party, who were well aware of my sensitivity to my portrayal, advised me not to battle the image problem. They said, “Advaniji, in fact, it helps the BJP to have one leader who is projected as a liberal and another leader projected as a hardliner.”

Also read: A lesson from the Vajpayee school of large-hearted leadership

In the wake of being falsely charged in the ‘hawala case’, I had announced that I would not re-enter the Lok Sabha until I was exonerated by the judiciary. Therefore, I had not offered myself as a candidate in the 1996 parliamentary elections. It was Atalji who contested from Gandhinagar in Gujarat, in addition to contesting from his own traditional constituency of Lucknow. I was deeply touched by his public display of trust and solidarity towards me. Expectedly, he won with a huge margin from both constituencies, and although he later resigned from Gandhinagar to keep his membership in Lucknow, his gesture energised the party and gave to the people, at large, an unmistakable message about unity at the top in the BJP. It was the same message that had gone out from the party’s Maha Adhiveshan in Mumbai in 1995, when I, as party president, announced his name as the BJP’s Prime Ministerial candidate in the parliamentary elections in the following year.

Why did I make that announcement? There was much idle speculation on this point at the time, and some of it, sadly, continues even today. Some people in the party and the Sangh had chided me then for making the announcement. “In our estimation,” they said, “you would be a better person to lead the government if the party wins the people’s mandate.” I replied, and did so with all the sincerity and conviction at my command, that I disagreed with their opinion. “In the perspective of the people, I am more of an ideologue than a mass leader. It is true that the Ayodhya movement has changed my profile in Indian politics. But Atalji is our leader. He has a far higher stature and much greater acceptability among the masses. He has an appeal that transcends the BJP’s traditional ideological support base. He would be acceptable not only to the allies of the BJP, but, far more importantly, to the people of India.” Some of them insisted that I had made a big sacrifice by this announcement. However, I was steadfast. “What I have done is not an act of sacrifice. It is the outcome of a rational assessment of what is right and what is in the best interest of the party and the nation.”

Along with all our other colleagues, the two of us worked together to bring the BJP to power in 1998. I served as his deputy in the government. This relationship was formalised when I was appointed Deputy Prime Minister on 29 June 2002. I said to the media that day: “It is a matter of honour for me and I wish to thank the Prime Minister and all our partners in the NDA.” I added, however, that this did not signify any change in my job profile. “The Prime Minister used to consult me even earlier and I have been doing similar kind of work before. Yes, in the eyes of the public and my cabinet colleagues, my responsibilities have increased.” I also hastened to scotch rumours, which were being spread by some hostile elements in media and political circles, that my formal elevation as Deputy Prime Minister would lead to the creation of a parallel power centre.

The 2002 presidential election

In early 2002, discussions had begun within the BJP and the NDA about who should be our candidate in the election for the new President of India as Dr K.R. Narayanan’s term was coming to an end in July. Our internal deliberations were guided by two overriding criteria. Firstly, the new President should be a person of high stature, and suitable in all respects to occupy the august office. Secondly, we wanted the person to be preferably outside the ranks of the BJP because of our keen desire to convey a message to the nation that our party believed in inclusivity.

Surprisingly, our choice promptly zeroed in on a candidate who had nothing whatsoever to do with our party. Rather, he was closely associated with two former Prime Ministers, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, of the Congress. It was Dr P.C. Alexander, who was then serving as the Governor of Maharashtra. It was I who first proposed Dr Alexander’s name to Atalji and to other key leaders in the NDA. I had been highly impressed by his performance as Governor, and so was Atalji, who readily agreed with my suggestion. His name found ready and enthusiastic acceptance from among other leaders of the constituent parties of the NDA. However, due to opposition from the Congress for the candidature of Dr P.C. Alexander, the NDA chose another eminently worthy candidate, Dr A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, to succeed Dr Narayanan.

I would like to mention here a significant development that took place at the time. One day I received a call from Prof. Rajju Bhaiyya, who was then Sarsanghchalak of the RSS, saying that he wanted to discuss something important with me. I invited him over the following morning and, over breakfast, he narrated to me the details of a meeting he had had with Atalji the previous evening. “I had gone to the Prime Minister’s residence to discuss the issue of the Presidential election. I suggested to him, ‘Aap hi kyon nahin Rashtrapati bante?’ (Why don’t you become the President?) I gave my reasons for making this suggestion — principally that, in view of his knee trouble, it would be less taxing for him to shoulder the responsibility of Rashtrapati Bhavan. Besides, the people would consider him to be the ideal choice in view of his stature and experience.”

I asked him what Atalji’s response had been. Rajju Bhaiyya said that Atalji had been hesitant. “He said neither yes nor no. I therefore think that he has not rejected my suggestion.” I then mentioned to Rajju Bhaiyya that the NDA leaders had formally met only three days earlier to discuss the issue of the Presidential election and unanimously resolved to authorise the Prime Minister to finalise a suitable, nationally acceptable candidate. In the end, everybody unanimously accepted Atalji’s decision in the matter.

A relationship moored in mutual trust and respect

Experience has taught me that long-lasting and fulfilling relationships in politics are possible only on the basis of mutual trust, respect and commitment to certain shared lofty goals. Politics driven by power play is, by its very nature, competitive and conflict-ridden. But politics driven by a common ideology and nurtured by common ideals and samskaras is a different matter altogether. When a higher purpose brings a set of people together, they learn to overlook and sideline small matters and personality-related issues. Many people have asked me, “How did your partnership with Atalji endure for over fifty years? Did you never have any differences or problems with him?”

I can well understand the puzzlement in this question. But I can also say, in all honesty that, contrary to what some people have been speculating since decades now, the relationship between Atalji and me was never competitive, much less combative. I do not imply that we never had any difference of opinion. Yes, we have sometimes had divergent views. Our personalities are different and, naturally, our judgements on individuals, events and issues have differed on many occasions. This is natural in any organisation that values internal democracy. However, what lent depth to our relationship were three factors. We both were strongly moored in the ideology, ideals and ethos of the Jana Sangh and the BJP, which commanded all its members to put nation first, party next, and self last. We never allowed differences to undermine mutual trust and respect. But there was also a third and very important factor: I always implicitly and unquestioningly accepted Atalji to be my senior and my leader.

From the very early stages of our association, I always used to submit to whatever Atalji decided with regard to organisational and political matters. I would put forth my views but once I sensed what Atalji wanted, I would invariably go along with his viewpoint or preference. My responses were so predictable that sometimes my colleagues in the party, or leaders in the RSS, would express their displeasure over what they perceived as my inability or unwillingness to disagree with Atalji’s decisions. This, however, made no difference to my conviction that Atalji’s must be the last word in all party-related — and, later, in government-related — matters. Dual or collective leadership is a poor substitute to unity in command. I used to tell my colleagues, “No family can stay together without a mukhiya (head), whose authority is unquestionably accepted by all its members. After Deendayalji, Atalji is the mukhiya of our family.”

Here I must also add that Atalji had an accommodative approach towards me. If he knew what my thinking was on a certain issue, and if he did not have serious disagreements over it, he would readily say, “Jo Advaniji kehte hain, voh theek hai.” (What Advani says is right.) Thereafter, the matter under discussion would be immediately clinched.

Throughout the six years of the NDA government, speculation about the non-existent ‘Atal-Advani conflict’ was a favourite pastime for few in the media and political circles. Atalji refuted this speculation on numerous occasions, both within Parliament and outside. In an interview given to India Today, he was asked: “How are your relations with Home Minister L.K. Advani? Is the BJP pulling in different directions?” His reply was forthright: “I talk to Advaniji each day. We consult each other daily. Yet you people speculate. Like a record stuck in a groove. One more time, let me say there is no problem. When there is, I’ll let you know.”

Excerpted with permission from Rupa & Co.