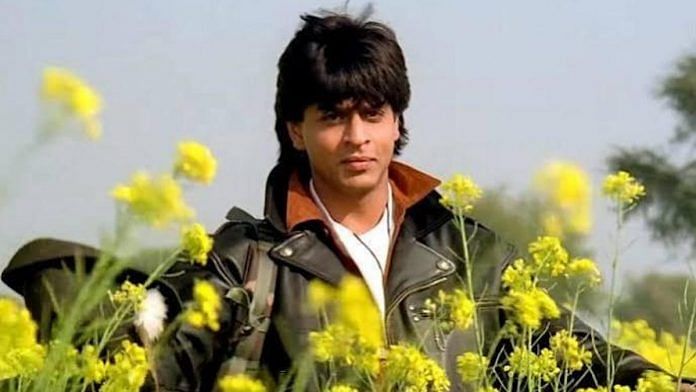

I started with the ladies I knew best, those born in the early 1980s into socio-economic privilege, those just like me. This was an easy place to begin. I typed up a survey questionnaire seeking anonymous interviews. It sought basic demographic information and willingness to participate in follow-up conversations. Through coffee runs and catch-up sessions between 2013 and 2017, I discovered that the fandom of elite thirty-something women took a similar shape. We were very different people, but we saw Shah Rukh with the same pair of eyes. Ours was the last generation of Indians to navigate adolescence and early adulthood without a smartphone. Prannoy Roy relayed the news of the world to us. We could never stalk our high school crushes on Instagram. In the 1990s, we discovered Shah Rukh. We were his first set of fans, the first generation of women to claim him. We made him a superstar.

As fangirls grew up to become fan-women, many stopped following Shah Rukh’s movies but continued to obsess over his interviews. One fan explained: ‘Recently, he said something like how he can dignify a woman so much that she will fall in love with him. Which other star talks like that about women in India?’

In 2018, a charming story about a young Bengali fangirl did the rounds of Indian news media. The woman complained that the romance in Khan’s films had ‘ruined her life’. She accused the actor of making her a hopeless romantic, forever expecting the ‘perfect proposal’ from a man, one where he would emulate her hero’s on-screen routines. Eventually, she upended gender roles by proposing marriage to her boyfriend with music and poetry. Abandoning all expectations of the man behaving like Shah Rukh’s romantic avatar, she took on the role of Khan in the proposal.

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan was India. And then India changed

The women who responded to my call for interviews felt romantically ruined by Shah Rukh as well. Most were approaching their mid-thirties. Each woman was thoughtful about her fandom. Marital status was an organizing principle of selfhood— it was often the first thing fangirls mentioned about themselves. Half of the eighty upper-class fans I was able to follow and interview repeatedly were married.

Love of Shah Rukh wasn’t the only common trait shared by married fan-women—a majority of them did not work outside the home. Several women dropped out of the workforce during the four years we knew each other. These choices were always deemed ‘natural’, typically triggered by pregnancy. Nearly everyone I interviewed struggled to piece together a coherent timeline or narrative of how they became full-time housewives. It just happened. I heard that phrase a lot. A sense of social persecution, confusion and guilt loomed large when we talked about employment decisions. After four years of difficult conversations, I traced three distinct groups within the married pool of fan-women. Each felt judged by the other.

The first group comprised women who had never cultivated a career-minded sense of self. Much like their own mothers, this group felt that motherhood and family were their calling, a core source of meaning and purpose. A thirty-six-year-old fan said, ‘There was no point in doing something you did not care about or enjoy, or would not do well in, especially when I do not need to work to survive. My husband loves me and makes good money. He gives me all I ever need. None of my close friends work either and we spend a lot of time with each other. I have a good life. But I do feel judgement from working women and society towards housewives. Nowadays, among the higher strata of society, a career has become a status symbol for women. I know women who ask their husbands to help them set up some small business, not because they care about the work but because they want the label of being a career woman. I don’t care and don’t really need to impress anyone other than my family.’

A second group of women felt their professional identities were vital to their personhood. However, they gradually gave up careerist ambitions after childbirth. While some experienced social pressure, the decision to leave paid work was rarely framed as having been coerced. Most women claimed they were happy to have left ‘soul-sucking jobs’ and ‘male chauvinist pig office environments’. They felt great pride at being good mothers. But I sensed some regret. One woman reflected, ‘My husband is soft and funny, like Shah Rukh. He never told me to stop working, but it felt like the sensible thing to do. A child needs his mother. I did not want to miss out on spending time with my baby boy. My husband was doing very well in his job and we could afford to be a single-earner home. I hope I’ll return to work after my son is older, but it seems tougher each year. I’m not an artist or a businesswoman, I can’t work for myself. I did well in the office environment, but I know that the kinds of jobs I enjoyed need dedication and I need flexibility. Those are incompatible.’

Also read: Shah Rukh Khan is playing most difficult role – a good parent and impeccable public figure

The ability of upper-class homes to secure domestic workers does not seem to alter how motherhood tends to push women out of the workforce. As per data from CMIE for 2019, only ten per cent of mothers from the wealthiest segment of urban India held a paid job. Even with expanded maternity leave, employers offer little flexibility to handle jobs and childcare. Women often feel discouraged to resume employment as their husbands make significantly more money than them. The workplace feels exhausting – with its boys-clubs and their covert unfairness. Weighing the pros and cons of returning to paid work, many women find greater love, social recognition and self-worth in being caregivers, thereby steadily withdrawing from the world of paid employment.

A third group comprised a minority of married fans who attempted to be superwomen. They continued to work outside the home after motherhood. Overworked and stressed, these women were annoyed by the amount of housework they were still organizing and doing. Despite employing cooks and nannies, they felt disproportionately responsible for keeping track of groceries, children and elders. These women were lonely in their endeavours, as their husbands were rarely trained or socially configured to perform household duties. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 2018, an urban Indian woman spends five hours on household chores every day, while an urban man spends twenty-nine minutes on housework. India ranks in the bottom five countries of the world when it comes to the share of men helping in housework, alongside Pakistan, Mali, Cambodia and South Korea. It is hardly surprising that women admired how Shah Rukh would often be filmed in a kitchen—peeling carrots in DDLJ to cooking dinner for David Letterman.

As our conversations progressed, a few women confessed that quitting their jobs had left them feeling resentful. They felt betrayed by their husband’s lack of interest in their careers. A fan once told me, ‘I had always believed that marrying a good man would mean that my husband would always support my goals. But after I was pregnant, I realized that even the best men prefer it if women stay home. My daughter is five now, and my in-laws are keen that we try for a son. I have refused, but my husband doesn’t draw the line with his parents.’

For these married women, Shah Rukh had become a symbol of their youth, a time of optimism, a time when they believed it was possible to find a man who would love them as they were and always stand up for their choices. Real life required far more bargaining. A man could love you, he could be persuaded to marry you, he could be a terrific father, but he wouldn’t necessarily champion your freedom. ‘Sometimes, I watch those romance films of Shah Rukh’s with my teenage daughter and warn her,’ a woman said to me. ‘I tell her that there are no men like that in real life, no man will fight for you. You’ll have to fight for yourself. She laughs at me and can’t believe that I like such soppy films. She is far more sensible than I was at her age.’

Shrayana Bhattacharya trained in development economics at Delhi University and Harvard University. Since 2014, in her role as an economist at a multilateral development bank, she has focused on issues related to social policy and jobs.

Shrayana Bhattacharya trained in development economics at Delhi University and Harvard University. Since 2014, in her role as an economist at a multilateral development bank, she has focused on issues related to social policy and jobs.

This edited extract from Shrayana Bhattacharya’s Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.