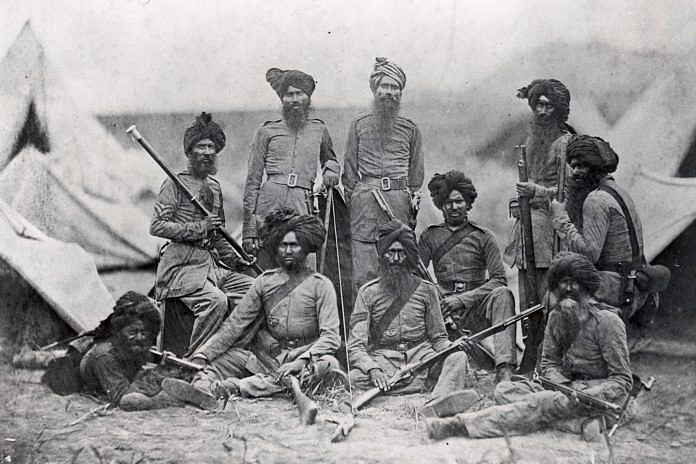

In the early twentieth century many Britons believed that Sikh men were the living embodiment of perfect soldiers. Major A. E. Barstow of the 2nd Battalion, 11th Sikh Regiment wrote in the 1920s that each Sikh was inherently “a fighting man” who could be counted as “the bravest and steadiest of soldiers.” They were, in his view, “more faithful, more trustworthy” than other widely recruited communities known to the British as “martial races.” Another British soldier remembered that “the Sikhs were better than the others” because they were “more loyal.” British perceptions of inherent Sikh loyalty and superiority influenced wider debates about recruitment and martial prowess across religious communities in India. Creating the image of the loyal Sikh soldier idealized—and set up unrealistic expectations for—all soldiers. Both Sikhs and non-Sikhs struggled to live up to this effusive praise. Instead, British efforts to define Sikhs as both a religious community and a naturally loyal band of warriors inspired anti-colonial soldiers and civilians to challenge such paternalistic definitions of Sikh identity. Sikh soldiers’ experiences of service, meanwhile, suggest that there were several unintended consequences of exalting a single community as inherently martial. In many ways, the imperial exaltation of Sikhs was the keystone of conflict in the twentieth-century Indian Army.

Twentieth-century British soldiers and officers had great confidence in Sikh soldiers because they believed that Sikhs had served in the Indian Army consistently and loyally since the days of the 1857 uprising. This rebellion had started as a mutiny in the East India Company’s Bengal Army and broke out into a wide-scale revolt across northern India. Its brutal suppression by British and Company forces resulted in the transfer of Indian territories to the British crown in 1858. Britain’s victory would have been impossible without the contributions of soldiers from Punjab, Nepal, and the northwestern borders—including many Sikhs—who joined the British in putting down the rebellion. Twentieth-century military pamphlets claimed that devotion to the British made “the Sikhs as a

body . . . loyal” in 1857.

These accounts of unwavering loyalty encouraged Sikhs to become the most disproportionately recruited soldiers in British imperial service. They made up 20% of soldiers despite being less than 1% of the population of India. As a result, they became the most paradigmatic “martial race” that British officials exalted as naturally loyal and “racially” fit to fight.

Sikhs’ disproportionate recruitment reveals larger tensions within imperial employment. Scholars have rightly pointed out that exalting Sikhs was part of a grander imperial effort to “divide and conquer” India by fomenting dissent internally. Praising a minority community like Sikhs, according to this view, created both bitterness and aspirational jealousy among those not recruited as “martial races.” Yet imperial rule was rarely stable or unquestioned, even by those exalted as the most loyal. This was no more evident than in the twentieth century, when anticolonial rebellion and reformist activism rose sharply within and outside the army. British attempts to define and promote the image of the loyal Sikh reflected colonial fears of losing control of soldiers. In many ways, Sikhs’ service in the Indian Army gave them the weapons to rebel.

Defining Sikhs, creating rebels

Despite some British soldiers’ assertions, there was no single definition of what Sikhs looked like, how they behaved, or what they believed. Regional and familial ties, alongside differences in class and employment, resulted in a plurality of Sikh identities. Even Indian Army recruiting manuals acknowledged initially that not all Sikhs made ideal soldiers. The Army Handbook for Sikhs, published in 1899, identified class, caste, and regional differences that affected a soldier’s martial potential. It maintained that agricultural Sikh Jats from northwestern India had the physical strength and indifference to Brahman dietary custom to be perfect soldiers. By contrast, it portrayed urban Sikh Khatris as reluctant farmers and Sikh Mazbhis as low-caste criminals. The army attempted to overcome these differences by encouraging strict definitions of Sikh identity to transcend regional and caste differences and create the perfect soldier. Civil servant Max Macauliffe, an “orientalist” scholar, greatly influenced army praxis through translations of Sikh texts and lectures to civil and military authorities. He claimed in 1903 that Sikh beliefs were a “comprehensive ethical code” that were valuable to the army because they inculcated “loyalty, gratitude for all favors received, philanthropy, justice, impartiality, truth, honesty, and all the moral and

domestic virtues known to the holiest Christians.” Commander-inChief of the Indian Army, Lord Kitchener (1902–9), wanted Macauliffe’s work translated into the “the ordinary Punjabi of the day” so that it could be disseminated “through every Sikh household in the country.” Although Kitchener and Macauliffe believed that Sikhs were naturally loyal, it was important to spread imperial interpretations of Sikh belief and practice to keep them that way. Kitchener was confident that Macauliffe’s pro-empire accounts of Sikh heritage would stimulate Sikh recruitment by making Sikh men feel proud about military careers. He also praised the army’s so-called class regiment system for isolating Sikhs from other communities in their own companies and battalions. This policy, in his view, allowed Sikhs to “keep up the purity of their religion” as was done in the nominally independent Sikh princely states of Nabha and Patiala. This really meant that soldiers had to police their own behavior and identities—and that of their fellow soldiers—to gain a position and remain in the army. This military-sanctioned view of Sikh “purity” was an attempt to codify “Sikhism” as compatible with military service.

Controlling narratives of precolonial Sikh heritage was an important element of defining Sikh identity for the army. Many South Asian soldiers and cantonment workers emphasized lineages of military participation that predated 1857. For example, in 1919, Jam-Hat Singh knew that his family’s military heritage preceded his grandfather’s participation in the siege of Delhi in 1857. He bragged to a British soldier that in 1750 his ancestors joined the Khalsa (elect) Sikh warrior fraternity, originally founded in 1699 by Guru Gobind Singh. Emphasizing both 1857 and the Khalsa allowed Jam-Hat Singh to honor his family’s precolonial and colonial military heritage simultaneously. Few Sikh soldiers understood their service to Britain as a clear choice between remaining “loyal” or “disloyal” to an unbroken history of imperial devotion. The Sikh Khalsa predated British presence in Punjab. It had gained political cohesiveness under Ranjit Singh and grew into an independent empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries before falling to the East India Company in 1849.11 Many soldiers joined British service in 1857 due to limited post-conquest financial opportunities, rather than inherent loyalty. Sikh heritage, therefore, both served and combatted British power. As anticolonial activism took new forms in the twentieth century, Sikhs had to make choices about which loyalties to honor. Some Sikhs emphasized their devotion to the British after 1857 to gain greater concessions from the imperial state. Others hoped to revive Khalsa rule and the memory of the Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845–46; 1848–49) to campaign against colonialism.

This excerpt from Kate Imy’s Faithful Fighters has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from Kate Imy’s Faithful Fighters has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.