One thing, however, was clear from the very start of the tour—the Indians weren’t in the best space mentally when they landed at JFK Airport in New York on their way to Jamaica [in 1971]. While on the one hand, they were expected to do well against a relatively young and inexperienced West Indies side, on the other, they were being picked on for reasons that had little to do with their cricket. To compound problems, Sunil Gavaskar had been nursing a painful ‘whitlow’ in his finger as the team boarded the aircraft in Bombay and was in extreme duress by the time the flight touched down in New York. Gavaskar recounted, ‘Soon after we reached the hotel, the manager, Keki Tarapore, took me to the hospital to get the finger checked. In the course of the flight, the swelling had increased considerably and the finger had turned so bad that the nurse who was assisting the doctor actually turned her face away on seeing the pus. However, the operation was eventually a minor one, and within ten minutes, I felt better. All I needed to do, I was told, was rest, and I would be good to go in about a week or so.’

With Gavaskar and Viswanath out with injuries, the Indians needed to use every resource in the two tour games leading up to the first Test in Jamaica, starting on 18 February 1971. After reaching the West Indies on 2 February, all the team had were two four-day games to fine-tune the final XI, with the first warm-up match slated to begin on 5 February in Kingston. This meant that the two days heading into the first practice game, 3–4 February 1971, were of utmost importance as far as acclimatization was concerned. However, calamity struck soon after the team landed in Kingston, with news coming in that the kit of almost the entire sixteen-member squad had not reached Jamaica. The Indians, it should be mentioned, had missed their scheduled connecting flight in New York, allegedly because of a mix-up by the airline staff—the team’s luggage had to be offloaded at JFK Airport and could only be sent via the next available flight. It seemed incomprehensible to many that the kit hadn’t been properly loaded the next day considering there was a near-twenty-four-hour gap between the two flights.

Seriously concerned over the non-availability of the kit, Tarapore, the manager, made multiple phone calls to the BCCI and the team’s travel agents who were responsible for ensuring smooth passage between New York and Jamaica. Things turned dire when the travel agents informed the BCCI that the team’s kit hadn’t been found at the airport and that they had documents to prove it wasn’t in New York. They circulated memos to show that the kit bags of all the players had left JFK Airport and had travelled to Jamaica on the same aircraft as the team. This sent the whole issue into a tailspin. With the team left to fend for themselves, Tarapore had no other option but to go back to the airport in Jamaica and ask the officials to check one final time if the kit had arrived from the US. To his amazement, he discovered that all the bags had been lying in the unclaimed baggage area at the Kingston airport for two days and, according to the officials, would have been removed had there been no claimant in the next day or so. The officials in Jamaica, it appeared, had goofed up, but were unwilling to own up to the mistake. It was just hours before the first game on 5 February that the Indians got their kit, making things that much more difficult for them to start with.

Also read: How Sunil Gavaskar took on West Indies 50 yrs ago & became India’s 1st sports superstar

While a section of the Indian press blamed the BCCI for the ‘mystery of the missing kit’, as the incident came to be labelled, others suggested that the board should have been more proactive, learning from its 1961–62 experience. That tour of the West Indies nine years earlier had been disastrous, culminating in a 5–0 series defeat. Things had started to go south when, even then, the Indian team’s kit did not reach Jamaica in time, leaving the players stranded in the city for the first two days without practice.

Prabhu, travelling with the team in the same aircraft in 1971, expressed surprise at how the entire team’s kit could have gone missing. In his characteristic lyrical prose, he wrote, ‘The night stopover at the Sherlock Holmes Hotel in Baker Street was interesting but of little use. On our onward journey, there was no trace of the cricketers’ baggage for two days. This was certainly one where Dr Moriarty scored. One felt that James Bond would certainly have delivered the goods in more than one sense, pinning it down to one of Doctor No’s henchmen in Kingston Town.’

Another issue, which affected some players more than others, was the growing political turmoil back home in states like West Bengal at the time of the tour. While the mounting unrest in Bangladesh, which finally resulted in the liberation of the country in December 1971, is formally documented to have started that year on 25 March, rising tensions in areas of Calcutta could be felt from January of that year. Rusi Jeejeebhoy, who was from Bengal and travelling with the team for the first time, was the hardest hit, with no communication from home adding to his growing anxiety. The following was reported in the Times of India on 23 February 1971: ‘Indian cricketers have been distressed by the lack of news from home. This is particularly true of Rusi Jeejeebhoy as items on disturbances in Calcutta have appeared in the local press (in Kingston).’

The report went on to state that the BCCI, which had arranged for all correspondence to be directed through the West Indies cricket headquarters in Guyana, should think of a change in its stance, as the existing arrangement had been found unsatisfactory. None of the players had received any letters from home in their three weeks in the Caribbean—an issue that was considered unfathomable. The report quoted the players as saying it would be best if all mail was sent to the principal cricketing centres at the Queen’s Park Cricket Club in Trinidad, the Kensington Oval in Barbados or the Bourda Oval in Guyana, calculating a margin of seven days from the designated arrival of the team in each of these venues.

Also read: Ajit Wadekar, the ‘commoner’ who dethroned the Nawab and took Indian cricket to glory

It was against this backdrop of mounting pressure that Wadekar led his team into the first practice game against the West Indies Board President’s XI in Kingston.

Unlike today, where practice games are hardly ever well-attended, the first two tour games in 1971 witnessed thousands of spectators coming to the stadium to watch the Indian team in action. The West Indians love their cricket, and, as Gavaskar has often said, ‘These fans and the local media were an extension of the home side, making it that much more difficult for the touring team.’ If the reports of the games are an index, the media did all it possibly could to add to the pressure on the Indians and push them on the back foot even before the first Test match had started. In a piece for Sportsweek titled ‘No calypso ring in Wadekar’s capers’, one John Foster wrote, ‘Ajit Wadekar and his boys might become unpopular with the enthusiastic crowds here. The Indians’ scoring rate in the second innings nosedived to such an extent that the crowd which expects entertaining cricket from the Indians throughout the tour was sorely disappointed.’

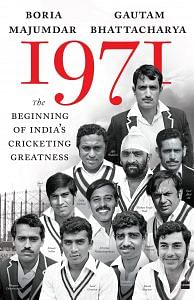

This excerpt from ‘1971: The Beginning of India’s Cricketing Greatness’ by Boria Majumdar and Gautam Bhattacharya has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from ‘1971: The Beginning of India’s Cricketing Greatness’ by Boria Majumdar and Gautam Bhattacharya has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.