Mohinderjit’s peripatetic early life is evident in the plurality of linguistic, cultural and religious influences in her poetry. Roughly a quarter of her songs reflect the Sufi tradition of ishq (love) in which the poet expresses a longing to be united with the divine or a lover. In describing the divine, she borrows heavily from the Islamic faith, using the terms Allah and Rabba. She also seems equally comfortable imagining devotional worship in mandirs (Hindu temples) as in the Darbar Sahib.

The four main preoccupations in Mohinderjit’s songs concern (i) her imagined youth in Punjab, even though she largely grew up in Burma and Iran; (ii) romantic love, especially the pain of separation from her husband; (iii) excitement about moving to America; and (iv) the loneliness of her later life in the United States.

The first predominant theme in Mohinderjit’s songs is an imagined nostalgia for a childhood in Punjab that she never experienced, shuttling from Burma to Punjab to Iran to Punjab to the US. Her songs about Punjab contain many of the stock tropes from the barahmasa folk song, including the stereotypical images associated with nature (for example, the arrival of the black rain clouds).

‘The Cold, Cold Wind Blows’ is an evocative song about a theeyan (women’s festival), a favourite subject of Punjabi women’s folk songs. The theeyan festivals occur during the arrival of the rainy season in Punjab; it is a time when women return to their home village where they traditionally gathered together to sing and dance. In this setting, it is socially acceptable for women to voice their complaints about topics that would otherwise be taboo, such as vexing mothers-in-law, sorrows and hardships in their lives, and difficulties with husbands.

Ṭhandi thandi vagdi hava vich bulle vagde

The cold, cold wind blows, filled with fierce winds

Saun da mahina ghatan charh aian

The rainy season has arrived and dark rain clouds have

gathered…

Arsha ton aian parian, rang-birange gihne pa ke,

nange pairi, pairi jhanjaran

Angels came from the sky wearing colourful necklaces and

anklets on their bare feet

Nach-nach pavan dhamalan dharti te

They forcefully dance on the earth…

Chal sajna mele chalie, mele aian theeyan da

My friend, let’s go to the fair. The women’s festival has come.

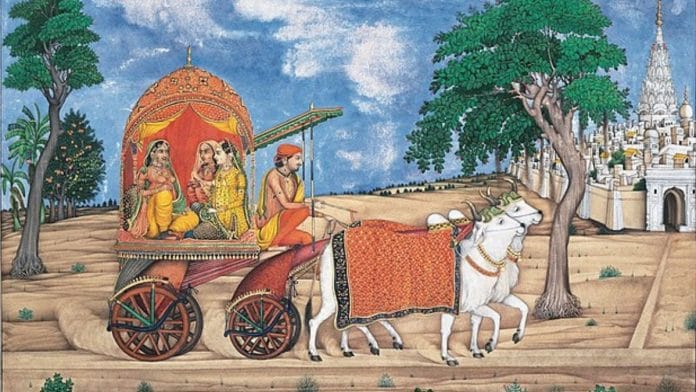

This song closely resembles a traditional Punjabi women’s folk song. There is an emphasis on natural elements that represent metaphors for intense feelings of foreboding and excitement. The language is informal, in the style of an ordinary village girl caught up in the anticipation of joining the fair. The imagery conveys women embracing their power, in the forcefulness of their joy in dancing, taking charge of the bullock carts, and the fierce winds signalling the arrival of their special festival.

The second dominant theme in Mohinderjit’s poetry is her longing for her lover, which presumably was her husband living abroad in the United States. However, her lover’s identity is ambiguous in the song. Her love poems invoke the concept of ishq, or an intense longing for a lover or God, which is borrowed in Punjabi music from the Perso-Arabic cultural influence in South Asia.

It appears that her songs were influenced by Bollywood films. According to Rachel Dwyer, Hindi film music is one of the most popular forms of poetry in India with ‘a rich idiom of love’ that ‘draws on a whole range of Indian lyric traditions, including the folksong and the Hindu devotional lyric, but is most closely connected with the Urdu lyric’. For Mohinderjit, ‘songs allow things to be said which cannot be said elsewhere, often to admit love to the beloved, to reveal inner feelings, and to make the hero/heroine realise that he/she is in love’ (Dwyer 2006: 292).

Mohinderjit’s love songs fashion herself and her lover in the immensely popular ballads of the doomed Punjabi lovers, Hir and Ranjha (Deol 2002; Malhotra 2017; Mir 2006, 2010; Singh 2016). This narrative tells the story of the tragic love between an intelligent, beautiful woman named Hir, who defies her powerful family who oppose her relationship with her lover, Ranjha.

Many of the popular songs about Hir and Ranjha concern their painful separation after the heroine is forcibly married to another man. This legend often ends with both lovers taking their lives by consuming poison rather than living apart. Mohinderjit makes her identification with Hir explicit by asserting in her songs: ‘Hir should exist with the name, Mohinderjit Kaur.’

The two songs that Mohinderjit spontaneously sang for me expressed her longing for her husband during the difficult years of separation after marriage (Image 3.3). Again, Mohinderjit casts herself and her husband as the most popular romantic figures in Punjab, Hir and Ranjha.

In the song ‘Hir cries out’, she describes the distress she felt after the train took her Rānjha away to a foreign land. She is left behind crying at the charkha (spinning

wheel), making clothes in Punjab. She pleads with the Ranjhas (the husbands) not to forget their wives back home ‘[as] our blossoming youth fades’.

Mohinderjit sang the second song, ‘Deson pardes’, at her husband’s funeral. She negotiated this final loss of her husband through her memory of her earlier painful separation after marriage when he left for California and she remained in Punjab. The song is a dialogue between herself and her husband, imagined as the tragic romantic legends, Hir and Ranjha.

Deson pardes ae te, main tur chalia

[Ranjha] I’m going far away, leaving home for a foreign land

Dikhin kite bhul na javin mere pichle piar

[Hir] Don’t forget your first love

Hir merie ni bhul javin mere pahile vale piar

[Ranjha] My Hīr, forget your first love

Jan valia das ja apna than te tikana

[Hir] Tell me the address where you’re going

Jithe likh likh rudna dian chithian main tainun pavan

[Hir] Where can I send my love letters to you?

Sajna, main tainun pavan

[Hir] Darling, [tell me your address] so I can send them to

you.

Na mera than te na hi mera tikana

[Ranjha] I don’t know where I’m going. I have no address or

place

Ni dil apna main tere dil vich rakh jana e Hire merie

[Ranjha] I’ll keep my heart in yours, my Hīr

Ni dil apna main tere dil vich rakh jana

[Ranjha] I’m going to keep my heart in yours

Jane valia, ajj teri Hir kukan mardi

[Hir] Departing lover, your Hīr calls out to you.

Chadd ke na javin Ranjha rondi apni Hir nun

[Hir] Don’t leave me crying, Ranjha, your Hir is crying

Hir kukan mardi

[Hir] Your Hir calls out to you.

Chadd ke na javin Ranjha rondi apni Hir nun

[Hir] Don’t leave me crying, Ranjha, your Hir is crying.

Mohinderjit’s song is a powerful testament to the collective experience of the thousands of wives who were left behind in Punjab after their husbands migrated all over the world beginning in the late nineteenth century. This source material is valuable given the paucity of research on the transformations in women’s lives in Punjab as British colonialism took hold of the region in the late 1800s and their husbands dispersed throughout the world.

This excerpt from ‘Punjabi Centuries: Tracing Histories of Punjab’ edited by Anshu Malhotra has been published with permission from Orient Blackswan.