Sardar Patel was far more direct and clear than Mahatma Gandhi when it came to assuring prosperity to the industrial class, says a new book about India’s ‘Iron Man’.

Along with the mills, the number of people working for them in Ahmedabad also grew rapidly — in the first half of the 20th century, the number of mill workers grew from 16,000 to 1.3 lakh.

This didn’t necessarily make the city any better. “In 1916 the mortality rate of the city population was still 39.22 per thousand or double that of Surat. To the existing mud were now added smoke and soot.”

The city’s fortunes changed with the end of the First World War: “Before the war, Ahmedabad was an unknown, parochial place lightly ruled by the British [but after the war it became] a financial and political base for the Indian National Congress and a leader and prototype of New India.”

The First World War also transformed the face of the textile businesses of Ahmedabad. “The war converted the mills and their agents into powerful industrialists. Still, in keeping with traditional policy [of saving rather than over-capitalisation], this success was achieved so quietly that even competent observers failed to notice that Ahmedabad was destined to play a very important role in the near future.” One man, however, caught on early: Mahatma Gandhi.

Gandhi could do no better than settle in a modern place that had preserved some ancient structure, so that from there he would travel and study what he later came to call the “four sins [economic, political, social and cultural] of an Indian identity”.

When the plague came in the monsoon of 1917, mill owners offered workers bonuses of up to 70-80 per cent of their salary to stay on in Ahmedabad — instead of running away as any sensible person confronted with plague would do.

When the disease receded, the bonus was withdrawn. But for mill workers earning a bare minimum salary, taking money away was unacceptable. The workers demanded a minimum of 50 per cent raise in their salary but were offered a 20 per cent raise instead. The threat of a lockout grew.

As 1918 rolled in, the dispute reached a flashpoint. By February, Gandhi was asked to intervene. There were two reasons for asking Gandhi to come in and his subsequent success in resolving the dispute:

[A]part from the great pressure he could bring through his prestige [. . .] Ahmedabad’s business leaders seem never to have forgotten that Gandhi was by caste a bania [trader caste] like themselves. During negotiations with Gandhi who was representing the labour union, the president of the Mill Owners Association remarked that he and Gandhi could find a compromise since both were banias.

This conflict led to Gandhi declaring that he would fast — neither eating food nor using a car — until the mill owners and workers came to a negotiated settlement. The talks settled at around a 35 per cent pay hike. The mill owners told Gandhi that they would do whatever it took to break his fast but Gandhi was resolute: It had to be a genuine compromise which worked for both sides. He said, “You must not give anything for my sake; do so out of the respect for the pledge of the labourers, and in order to do justice.” By this time popular opinion was also starting to swing towards Gandhi, who had emerged as a national leader.

Finally, an arbitrator was appointed and the mill workers agreed to accept a 27.5 per cent rise in wages and await the arbitrator decision on a higher final settlement. This movement also paved the way, partly due to sympathies among many mill owners for Gandhi’s cause of “maintaining harmony between capital and labour”, for the creation of the Textile Labour Association or Majoor Mahajan in 1920.

This was also one of the starting points of Gandhi and Patel’s relationship with capitalists and labour, and their being the interface between the two. As we will see later in this book, both Gandhi and Patel had a far more accommodating and tolerant attitude towards Indian businesses and businessmen compared to other prominent leaders like Bose or Nehru. (Nehru also subscribed to the Marxist idea that capitalism is, in a sense, a stepping stone towards fascism, and considered business as inherently exploitative and reactionary; it certainly didn’t help matters that the British had entered India through what became one of the world’s first multinational corporations, the East India Company).

Gandhi’s Theory of Trusteeship where he imagined evolved business leaders holding their wealth ‘in trust’ for the benefit of society and not consuming more than their needs was considered utopian and a cop-out by many Congress socialists. But Indian industrialists had supported the Congress with funds and in kind for years, and the mass growth of the Congress had come with the financial assistance of the homegrown business community.

While Gandhi couched his support for indigenous businesses and industrialists in lofty rhetoric, Patel was far more direct and clear that having taken consistent assistance from industrialists through the freedom struggle, it was the job of the Congress to ensure that the Indian business community thrived after Independence, which he believed would naturally bring the added and much-needed benefits of jobs and wealth creation in an impoverished country.

G.D. Birla, one of the industrialists both Patel and Gandhi had close association with, said about Patel:

Sardar Patel was not a revolutionary. He was essentially a man of constructive ideas. Many a time he utilised my help and money. I would get a telegram, sometimes just two words — “Come immediately” — and when I arrived he would tell me what I had to do. Inevitably the question of collection [of money] would come up. Once I told Patel what Gandhi said to me, “I do not like the Sardar collecting money from businessmen.” His reply was characteristic: “This is not his concern. Gandhi is a Mahatma, I am not. I have to do the job.”

It was Sardar Patel who perhaps first realised, long before Sarojini Naidu would joke about it, that it cost a fortune to keep Gandhi in poverty. As Patel’s biographer D.V. Tahmankar wrote, “It is claimed, not without reason, that Mahatma Gandhi’s triumph over the British Raj was due very largely to Patel’s extraordinary powers of organisation — powers that included the ability to raise vast sums of money needed for the freedom movement.”

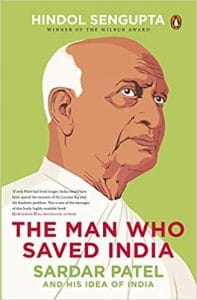

This excerpt from the 2018 book The Man Who Saved India by Hindol Sengupta has been taken with due permission from the book’s publishers, Penguin Viking.

This excerpt from the 2018 book The Man Who Saved India by Hindol Sengupta has been taken with due permission from the book’s publishers, Penguin Viking.