R. came in this morning. He brought some luscious mangoes. I fretted to find that you were not here to share them.

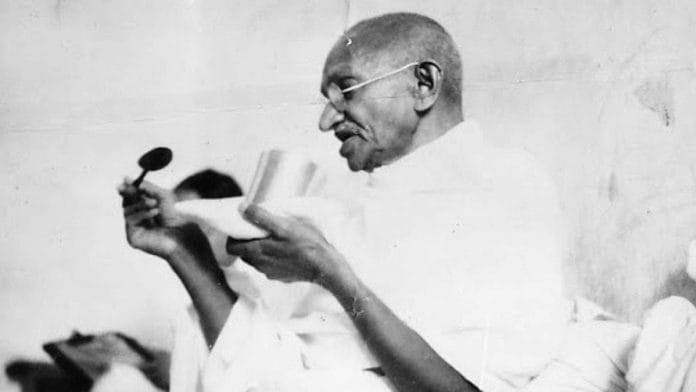

Gandhi, 1920

On a warm May morning in the spring of 1920, Gandhi looked at a box of mangoes and yearned to share. His response to those “luscious mangoes” reveals his diet at its most human. His delight for the simple pleasures of the fruit merged with the joy of sharing. Twenty years later, another box of mangoes arrived as “medicine” for a group of patients he was helping to treat. The sweet aroma of the fruit led him to eat a few himself. It is unclear how many he devoured, but his response was ferocious. “Mango is a cursed fruit,” he declared. “We must get used to not treating it with so much affection.”

In 1920, Gandhi delighted in mangoes; twenty years later, he cursed them. What accounts for this dramatic shift? As a young man, he radically changed his relationship to food: what was once a treat for his palate became sustenance for his soul. But that evolution occurred well before the earlier box of mangoes arrived. By 1920, he had rejected sweets, experimented with a saltless diet, and vowed to eat only five food items per day. Yet he remained eager to share those mangoes. The fact that the second batch arrived as medicine helps to explain his anguish at having eaten them. Yet Gandhi often rejected food even when it was not meant for others—vowing to treat ginger as “forbidden,” for instance, and criticizing chocolate. Conversely, the possibility of sharing did not automatically lead him to delight in flavorful treats. On the contrary, he condemned the routine giving of sweets as a harmful habit that should be abolished.

The ambivalence in Gandhi’s relationship to mangoes reveals a larger tension at the center of his diet, a tension between seeing food as an instrument of service and celebrating food for its own sake. The author E. B. White once wrote, “I arise in the morning torn between a desire to improve (or save) the world and a desire to enjoy (or savor) the world. This makes it hard to plan the day.” Gandhi too struggled with that balance, as his mango travails make clear. At stake was his ability to live a life that was passionate but not selfish, joyful but not lustful. The difficulty of discerning healthy desire from unhealthy lust is revealed by the most important detail in Gandhi’s encounter with the mangoes he yearned to share: their intended recipient.

Also read: Why Gandhi and Ambedkar never engaged with Hedgewar, the founder of RSS

Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, a dynamic anticolonial activist, was the founder of one of India’s oldest women’s organizations. When Gandhi saw her for the first time, she was conducting an orchestra as it performed a piece she had written in honor of the Indian National Congress. In 1919, Gandhi met Chaudhurani in Lahore and reported “bathing in her deep affection.” He was fifty. She was forty-seven. Both were married. Over the next year, the two exchanged a series of increasingly intimate letters. Their relationship became sufficiently close that Gandhi deemed it a “spiritual marriage.” What that relationship entailed has galvanized rumor-mongers, but no evidence suggests a physical dimension. Nevertheless, their relationship was sufficiently improper that Gandhi’s son asked him to end it.

In December 1920, some seven months after Gandhi wrote Chaudhurani about those luscious mangoes, he sent her a detailed note explaining why their relationship could not continue as it was. “Spiritual partners can never be physically wedded,” he explained. “Have we that exquisite purity, that perfect coincidence, that perfect merging, that identity of ideals, that self-forgetfulness, that fixity of purpose, that trustfulness? For me I can answer plainly that it is only an aspiration. I am unworthy to have that companionship with you.” With deep regret, Gandhi concluded, “I am too physically attached to you to be worthy of enjoying that sacred association with you.” He had tried to transcend the physical but, as with those “cursed” mangoes, he had failed.

Gandhi strove to avoid temptations that pulled him away from his purpose and into the desires of the body, but his goal was not to transcend the body entirely. He could walk away from Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, reject chocolate, and perhaps even avoid mangoes, but completely escaping food was not his goal. He recognized the limitations of his embodied being, but also believed that his diet could empower his spiritual growth. The link between his food, his body, and his soul led him to declare, “A perfectly moral person alone can achieve perfect health.”

It would be easy to dismiss Gandhi’s efforts to control his body as the self-centered obsessions of a Victorian prude. But as the philosopher Aakash Singh Rathore has written, “The discovery of oneself requires inwardness, turning away (pratyahara).” The ultimate goal of Gandhi’s inwardness was not control of his body; he wanted to change the world. As a young man in South Africa, he prepared a series of articles on diet and health in the midst of an epic confrontation with South Africa’s racist government. In the fall of 1942, imprisoned by the British, he took the opportunity to author another text on diet. Although separated by more than three decades, these writings are remarkably similar. The basic principles of his diet remained constant throughout his adult life. Equally consistent was the fact that his dietary concerns would not wait for politics, even dramatic conflicts like his struggle against South African racism and his final battle against British imperialism. Gandhi’s diet did not replace more political concerns. His diet was political.

He opposed the salt tax while exploring how to cut salt from his diet. He championed the rights of Indian indentured laborers forced to harvest sugar in terrible conditions, and he rejected sugar itself. As his food came to reflect his purpose, he learned to eat better and to live better—to eat and to live in the service of others. At least, that was his goal.

Also read: Gandhi never celebrated his birthdays, but made an exception on his 75th. For Kasturba

As his relationship with Sarala Devi Chaudhurani and those “cursed” mangoes makes clear, Gandhi’s conflicted relationship to the body defied the distinction between self and society by linking gender, sexuality, and diet. He strove to empower women as leaders, and saw culinary reform (and particularly raw food) as a way to free women from labor in the kitchen. His embodied politics subverted the colonial practice of equating women with the body and men with the mind—although his aversion to bodily pleasure could also reinforce such a gendered divide. “In much of philosophy, religion, and literature,” writes the political scientist Janet Flammang, “food is associated with body, animal, female, and appetite— things civilized men have sought to overcome with knowledge and reason.” For Gandhi, appetite was decidedly male. He lumped together the desire for flavor and the desire for sex in ways that could position women as seductive objects to be avoided, like chocolate. His praise of female purity was patronizing, and his patriarchal instincts led him to force many of his dietary practices on his wife and their children.

Later in life, one of Gandhi’s sons, Harilal, wrote him an angry letter. “Not to take salt, not to take ghee,” the letter declared, “not to take milk has no bearing on character. You say this is necessary in pursuit of self- control. But my view is that even before one cultivates self-control, there are other even more desirable qualities that need to be stressed—such as being unselfish.” Harilal had a point. His diet became a form of control.

Given that controlling his body at times overlapped with controlling his wife and children, Gandhi’s obsession with diet might be criticized as a masculinist fixation.

Gandhi’s rejection of certain norms of masculinity coincided with his rejection of sex and his efforts to “conquer” his palate. Was he replacing one form of control with another? In confronting the messiness of gender, sex, and food, he transgressed certain social lines while strengthening others. The note he sent Sarala Devi Chaudhurani concerning those “luscious mangoes” brims with longing and desire. After describing the newly arrived fruit, Gandhi yearned for Chaudhurani’s presence and noted that he awoke “at our usual time but turned in again. I did not watch the sunrise. Had you been here I know you would have dragged me to watch His Majesty coming in.” Pining to share a sunrise and a case of mangoes, Gandhi revealed the absence at the heart of desire, but also the way in which attending to absence can become a kind of presence. “To take pleasure in an activity is to engage in that activity while being absorbed in it,” writes the philosopher Talbot Brewer. Elaborating an old Aristotelian conception of pleasure as wholehearted attention, Brewer points to a tension inherent in Gandhi’s struggle with desire. By attending to his longing, Gandhi found pleasure in desire itself.

Gandhi did not want to enjoy his desire for sensual pleasure. He wanted to transcend it. His approach to other forms of desire was more complicated, however. Even at his most austere, he never rejected the pleasure of good company. It would be tempting to distinguish between the flavor of those mangoes and the joy Gandhi found in his relationship with Chaudhurani. Whereas one pleasure risked the slavery of the senses, the other freed him to enjoy even the absence of the object of his desire.

This excerpt from Gandhi’s Search for the Perfect Diet: Eating with the World in Mind by Nico Slate has been published with permission from Orient Blackswan.

This excerpt from Gandhi’s Search for the Perfect Diet: Eating with the World in Mind by Nico Slate has been published with permission from Orient Blackswan.

The Arabs swear by dates …