Many years back when I visited Allahabad, home to both the Nehrus and Feroze himself, I was struck by the contrast. Tourists made a beeline for Anand Bhawan, Moti Lal Nehru’s mansion, which has been gifted to the nation, but almost no one, including family members, bothered to pay their respects at the neglected Parsi cemetery where Feroze’s grave lies. His brothers and sister erected a gravestone over the ground in which an urn containing some of his ashes is buried. But Feroze’s funeral was conducted with full Hindu rites and his two sons, Rajiv and Sanjay, lit the funeral pyre. The only concession to his Parsi roots was that a Zoroastrian priest was first permitted to read the Gatha prayers over the body with only members of the community and his sons present.

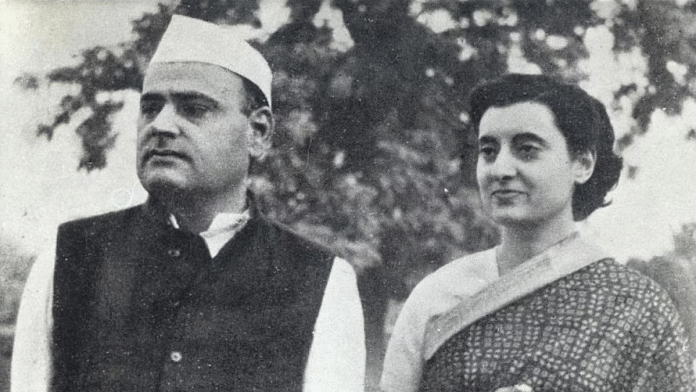

The marriage of Indira and Feroze seemed to be a mismatch from the start. Indira was shy, reserved, secretive, dignifed and discreet, with a sense of the importance of her family’s place in history. Feroze was gregarious, good-hearted, loud, fun-loving and slightly feckless. When he was courting Indira, he was totally in awe of the Nehrus. Feroze had been adopted by his mother’s sister, Shirin Commissariat—one of the first women surgeons in the country—at Lady Dufferin Hospital in Allahabad. Feroze was the son of Jehangir Gandhi, a marine engineer, and his wife Ratti. Both were from middle-class families in Gujarat who settled in Bombay. Feroze was the couple’s fifth child and the unmarried Shirin asked to be allowed to take charge of her nephew’s upbringing and education. After Jehangir’s untimely death, Ratti and her children spent a large part of their time in Allahabad. (A rumour that Feroze was the love child of Shirin and a prominent Punjabi lawyer based in Allahabad is not backed by any evidence other than small-town gossip.)

As a schoolboy, Feroze came in contact with Indira’s ailing mother Kamala Nehru, to whom he was devoted. Kamala in turn was fond of the helpful youth who was always ready to offer his services and give company to the lonely invalid. Partly because of his fascination with the Nehrus, Feroze took part enthusiastically in the freedom movement, much to the dismay of his Parsi family. They complained both to Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru that Feroze was ruining his future. Shirin even threatened that she would not fund his education in England if he continued to chase after the Nehrus.

Feroze was smitten by Indira from the time she was sixteen, but she had many admirers and suitors and did not give him any hint that she favoured him over the others.23 Both were students in England together, Indira at Oxford and Feroze at the London School of Economics. It was evident to a few close friends that in London their friendship had slowly blossomed into a passionate romance, but Indira did not breathe a word of it to her father. When the self-willed Indira, on her return to India, informed her father that she intended to marry Feroze, Pandit Nehru was shocked and displeased. In an attempt to prevaricate, he asked her to meet with the Mahatma. Seeing that Indira was determined, Gandhiji gave his blessing. The wedding took place amidst the upheaval of the Second World War, sandwiched between important Congress party meetings.24 Even as wedding preparations were underway, Nehru got cold feet because of the violent indignation among some people that the bride and groom were of different religions. (In north India, few even knew what a Parsi was; to them, the name ‘Feroze’ sounded Muslim.) Indira Gandhi’s biographer, Katherine Frank, wrote that the prospect of the marriage upset Nehru because Feroze lacked the pedigree and the connections that Nehru valued. He would not have been so

opposed had Feroze come from one of the patrician Parsi families of Bombay. Feroze had not completed his university education, had no professional qualifications and no prospect of a steady income. Eventually, they married in a Vedic ceremony. The only Zoroastrian touch was that Feroze’s mother, Ratti, persuaded him to wear his kusti under his khadi sherwani.

But this was only a token assertion of Feroze’s Parsi roots and suitably clandestine. He neither mixed in Parsi society nor followed any Zoroastrian customs. Unlike most Parsis, his upbringing in Allahabad meant that he spoke flawless Hindi and was even known to recite passages from the Gita with some expertise. The couple had two children: Rajiv, who became prime minister, and Sanjay, who was his mother’s key adviser during the Emergency and remained her trusted sounding board till his death in an air crash in 1980 at the age of just thirty-three.

Feroze and Indira drifted apart a few years into their marriage. One reason was that Nehru was possessive of his daughter and he insisted that she move to Delhi to serve as his official hostess when he was made prime minister of India. Feroze, whose easygoing nature concealed surprising reserves of pride, remained in Lucknow where he was the director of the National Herald newspaper. Some in the Congress viewed Feroze as a lightweight. He was fond of gossiping in coffee houses and had a reputation as a womaniser. He was adept with his hands and had a knack for gadgets. It was a skill that both his sons inherited and perhaps manifested itself in Sanjay’s enormous enthusiasm for setting up the Maruti factory to manufacture a small Indian car. Despite the generally cool relationship between Nehru and his son-in-law, the former helped Feroze get jobs, first at the National Herald newspaper in Lucknow and then as the general manager of the Indian Express in Delhi.

Feroze was elected for three terms as a member of Parliament from Rai Bareilly and was also a member of the constituent assembly. At the start of his parliamentary career, he was a backbencher who listened rather than participated. He came into his own gradually, making a famous maiden speech on 6 December 1955. He took aim at the Bharat Insurance Company, run by industrialist Ramkrishna Dalmia, and exposed the widespread misuse of funds. As a result of Feroze’s findings, Dalmia, then the richest man in India, was sentenced to two years in prison. The insurance industry was nationalised. Feroze’s greatest scalp as a crusader against corruption was that of the powerful Finance Minister T.T. Krishnamachari (TTK). In one of the first financial scandals of independent India, Krishnamachari was a casualty of the decision by the nationalized Life Insurance Corporation of India, at the behest of Haridas Mundhra, a shady businessman, to invest a huge sum of money in six ailing companies in which Mundhra owned a significant number of shares. Feroze established that the finance minister was not being strictly truthful when he said that the investments, made by sidestepping normal LIC procedure, were made to prop up the stock market. The LIC investments, Feroze revealed, were made on a day when the stock exchanges were closed and that it had every appearance of a bailout for Mundhra.26 Feroze’s accusations were confirmed by a commission of enquiry headed by the retired Bombay High Court Justice, M.C. Chagla. TTK, a good friend of Nehru’s, had perforce to resign. The prime minister was livid. (TTK was made finance minister again six years after his resignation.)

But his ‘feckless’ son-in-law had shown a reporter’s nose for a story and the instinct and zeal to execute an investigation. He was willing to undertake long hours of research to make sure he was on firm footing and was also willing to take on his own party in the interests of the truth, not least his own father-in-law. Feroze was not just muckraker-in-chief; he was responsible for getting the Protection of Publication bill passed by the Lok Sabha. The bill sought to protect journalists covering parliamentary proceedings from prosecution. Ironically, nineteen years later, during the Emergency, Indira Gandhi quashed her own husband’s law protecting press freedoms.

Even when Feroze moved to Delhi from Lucknow, he continued to live separately from his wife in his MP’s quarters, though he did eat breakfast every morning at the prime minister’s residence and was close to his sons. The estrangement with his wife, though, was so total that at one stage Feroze wanted to formally divorce Indira so that he could marry a beautiful young woman from a prominent Muslim family in Lucknow. Nehru put his foot down as he did not want the family name to be besmirched by scandal. He asked his friend Ramnath Goenka to find Feroze a job at the Indian Express in Delhi. Incidentally, after Feroze broke the Mundhra scandal in Parliament, he was relieved of his job and office car almost overnight.

This excerpt from The Tatas, Freddie Mercury & Other Bawas by Coomi Kapoor has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.

This excerpt from The Tatas, Freddie Mercury & Other Bawas by Coomi Kapoor has been published with permission from Penguin Random House.