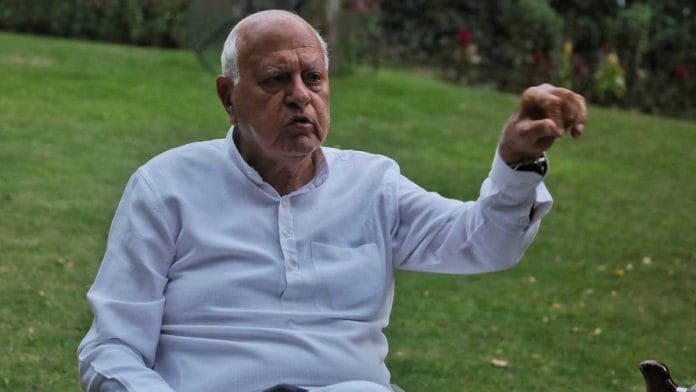

As early as 1990, Farooq had said that Kashmir needed to be on the right side of Delhi. This was a repetition of his first political statement, made in 1981, where he had said that he wanted to be a bridge between Srinagar and Delhi.

What happened in 1983, now that we think back on it, was that Farooq turned down Mrs Gandhi’s offer of an alliance. It is often said that Farooq acted imperiously in this

case, but we would do well to remember the context in which this refusal took place. After all, Farooq was the Sheikh’s son, and he had seen a whole flood of people who had come for his father’s funeral. He needed no further evidence of the Sheikh’s popularity. In his own mind, he admits that he was naïve in trying to improve upon his father’s image during his first chief ministership. But in Delhi, the real tragedy began with Mrs Gandhi’s dismissal of Farooq.

Farooq never got over that betrayal. It was politics, sure, but it was also personal. After the Emergency, she had come to Kashmir and met with Sheikh Sahib, and told him that she was seriously considering quitting politics.

‘How can you think that?’ he had demanded. ‘You are Pandit Nehru’s daughter. How can you quit?’

She stayed in Kashmir for a few days thereafter, being escorted to temples across the state by Farooq himself. She returned to Delhi a different woman. I’m only mentioning this because in Farooq’s mind, Indira’s dismissal of him was not just sad, but stunning, given that she was the one who pushed and prodded the old Sheikh to decide on his successor, to choose Farooq. To her, he seemed to be the more trustworthy option. Perhaps she was swayed by Farooq’s modern outlook, his foreign exposure, and his ease with English as well as with Kashmiri and Urdu. We’ll never know for sure, but for her to have dismissed him after this deep personal context was a betrayal he would always carry in his heart.

To be sure, her treatment of him has often been repeated thereafter. It was the problem with Narasimha Rao, as much as it was with Vajpayee. The latter was far too smart as a politician. He would never show that he didn’t want Farooq. But Narasimha Rao had planned the whole business of separatists joining the elections in 1996. Each politician was different in his method of handling Farooq, but the ultimate outcome only proved the same thing: Delhi never understood Farooq. There was something about him that was simply beyond the capital’s comprehension. He was always the more difficult option because even when Delhi had other preferences, because of its limitations, Farooq would become the fallback option. But he was a difficult option because he could not be pushed around, neither could he be controlled.

Also read: Indian govt doesn’t trust Jammu & Kashmir police—neither do Kashmiri Muslims

So when, in June 2000, the assembly in Kashmir convened for a week-long special session to discuss the Autonomy Committee’s report and pass a resolution to accept it, Delhi was suspicious. It had its reasons. In its report, the committee recommended the restoration of the 1952 Delhi Agreement, in which the only areas that the Union government would be in charge of would be defence, external affairs and communication. It also recommended that Article 370 of the Constitution, which grants special status to the state, be made a ‘special provision’ in the Constitution instead of ‘temporary provision’. This was the last thing the BJP and its allies wanted. The party has always stood for the abrogation of Article 370 and for putting Jammu and Kashmir firmly at par with other states in the Union. Similarly, the NC has always walked this tightrope. Notwithstanding his popularity, Farooq needed Delhi’s understanding, if not support, in fighting the elections. Looking ahead to the 2002 assembly election, Farooq knew he had to deliver on his promises well on time.

I had heard from our man in Srinagar, K.M. Singh, that Farooq had told him that he had contested the 1996 elections because the Government of India wanted him to contest, and at that time he had told the government that he needed a plank to fight the elections. Autonomy had been that plank.

I think there was no better plank for the NC to fight the 2002 elections. Farooq said to me very honestly one day, ‘What is this whole hullabaloo about? All we wanted from Delhi was a statement that the resolution was being examined. The problem is that Delhi never understands us.’

Delhi wasn’t pleased.

‘What is your friend up to?’ Brajesh Mishra asked me. I was at this point heading the R&AW.

When I rang Farooq to speak with him, and to let him know that Delhi was concerned, he told me that he had been pleading with New Delhi to also appoint a committee, which could have a couple of cabinet ministers on it. However, there was no response to his suggestion from the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), and left with no choice, Farooq was forced to move this resolution in his assembly.

‘Why are you worried?’ Farooq asked. ‘Everybody has to be kept happy. Tell them not to worry, the resolution won’t get passed. Kuch nahi hoga.’ (Nothing will happen.)

But when the resolution was passed by the Jammu and Kashmir assembly, Farooq merely sent it on to the Union home ministry. He knew that the home ministry was headed by L.K. Advani, and he knew that with Advani in charge, nothing would happen. It gave him, he figured, some time to breathe as well as an election plank. But the thing was that Delhi was supremely unhappy. Members of the NDA government were upset, and a cabinet meeting was immediately called. It summarily threw out the resolution, saying it was not acceptable.

Farooq was infuriated.

Yet again, it was, in his eyes, a question of Delhi not understanding him or the games he needed to play to keep the NC in the political running in Jammu and Kashmir. Delhi, he felt, was being far more hardline than was necessary. Kashmiris were once again being shut out, with not even a chance at dialogue. The thing is – you cannot push Farooq around.

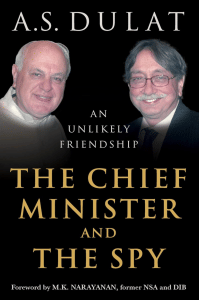

This excerpt from A.S. Dulat’s ‘The Chief Minister and the Spy: An Unlikely Friendship’ has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.

This excerpt from A.S. Dulat’s ‘The Chief Minister and the Spy: An Unlikely Friendship’ has been published with permission from Juggernaut Books.