Wazir Khan marvelled that such a young stranger, just recently arrived in the city, could swear obedience (as this was the meaning of the gesture) with such ease and certainty. Since the emperor was receiving visitors that morning, Wazir Khan invited Manucci to follow him to the palace, telling him that he should repeat the same rite he had just performed in the presence of the emperor. In the royal hall, they found Shah Jahan seated on the Peacock Throne, the famous solid gold chair studded with precious stones and diamonds, one of which, on the head of one of the peacocks adorning the throne, was probably the famous Koh-i-Noor:

When we got to the palace the king had already taken his seat on the throne. The secretary directed two men to present me to the king, while he (the secretary) should be talking to him. Accordingly, they did present me, ordering me to appear in front of the king at a distance of fifty paces, waiting until he should take notice of me before I made my obeisance. I had noticed that when the secretary reached the place where is the railing, he made one bow, such as I had done in his house, then, when close to the throne, he made three bows, and approaching still nearer, he began to speak to the king. After a few words he raised his eyes towards me, then the courtiers with me told me to make my obeisance, which I did (. . .). All those who were present before the king were standing: only one man was seated at the side of the throne, but his seat was lower, and this was the prince Dara, the king’s son.

After the audience was over, the secretary invited Manucci home and, in front of his son, suggested that he should stay with them, enumerating the many advantages this had for him. Manucci, who sensed an ill-concealed interest in the invitation, said he was honoured but politely declined. He justified his refusal by saying that he belonged to the Christian religion. In truth, his (more than understandable) intention was to return to the enclave in Surat because, he writes, ‘I wanted to find myself among Europeans’. However, Claude Maillé, the Frenchman with whom he stayed in the meantime, argued that refusing an introduction to the Mughal court would be the waste of an opportunity. So Manucci decided to stay on in Delhi:

As I was a youth, carried away by curiosity, but still more by the friendship shown to me by Clodio, and reflecting that I had already in him one friend who could do me some good in this kingdom, and be of help to me in some affair, I determined to remain where I was.

He was not wrong. Within a few days, his friend who had good contacts at court told him that Prince Dara Shikoh (1615–1659)— the person he had seen sitting next to the emperor—a generous man and well disposed towards Europeans, had heard about the young firangi’s arrival and was interested in meeting him.

Also read: Mughal history’s biggest puzzle solved by municipal engineer — where is Dara Shikoh buried?

Beside the fact that the prince was the designated heir to the throne, Manucci did not have the faintest idea about the person he was about to meet. He certainly did not imagine that, unlike Shah Jahan’s other sons, all men who were fundamentally devoted to warfare and hunting, Dara was a man of sophisticated culture and intellect and a spiritual person, who in some ways replicated his great-grandfather Akbar’s enlightened ways. Rather than to weapons and new conquests, the prince—a forty-one-year-old mystic, an eclectic philosopher and great visionary—had devoted a large part of his life to what he called the ‘mingling of two oceans’, his plan to bring Hinduism and Islam closer to each other by demonstrating the substantial correspondence between the principles of the two traditions.

This extraordinary prince was born in Rajasthan at Ajmer, in 1615; he was the firstborn son (in the male line) of Emperor Shah Jahan and Princess Mumtaz Mahal (the one for whose love her consort would build the Taj Mahal), and as well as the great-grandson of the great Emperor Akbar, the most illustrious among Mughal emperors. Dara had shown a precocious mystical inclination, which had led him, very young, to become affiliated to the Qādiriyya, one of the most ancient Sufi confraternities and to follow the teachings of the famous saint from Lahore, Mian Mir, whose eulogy he had read in 1635. His interest in the more ecstatic aspects of Sufism had led to frequent disagreements with the official Sunnite clergy of the courts in Delhi and Agra. Just like his great-grandfather Akbar, he enjoyed discussing religious matters with the Jesuit fathers, and encouraged them to exchange views with Muslim or Jewish wise men. Dara, who united in himself the figures of the Sufi mystic and of a Mughal prince, would pay for his scarce determination, if not his incompetence, in military matters, and lose his life in the impending struggle for the succession to the Mughal throne; he would be killed by his brother Aurangzeb, a champion of Islamic orthodoxy and a valorous warrior.

Of course, when he was admitted to the prince’s presence, an event that would mark a turning point in his life, Manucci knew nothing of how things would unfold. What counted for him was to make the best of the opportunity he was presented with. He took great care not to waste it because ‘the resolves of the great were like birds: if the bird-lime stuck to them, they were easily caught; but if they once flew away, it was very hard to lay hold of them a second time’.

When I reached his presence, and made the usual obeisance, he asked me if I could speak Persian (. . .). He was delighted at seeing a youth of not more than eighteen years and a foreigner, with such quick-wittedness that he had learned to make the proper obeisance without any shyness. Then I answered the questions, showing myself acquainted with Turkey and Persia and other important matters. The whole of my replies were in Persian, by which I proved to the prince that I could speak sufficiently well the language about which he had asked me.

Also read: Dara Shikoh had a dream. And it was about Ram

An eighteen-year-old European travelling in seventeenth-century India without a patron was, by itself, a peculiar occurrence; but even stranger was the fact that the youth demonstrated such confidence in the complex court protocol and exhibited a linguistic proficiency allowing him to communicate freely in Turkish, Persian and, with the officer who was assisting him, in French. Manucci was quick to understand that multilingualism was an asset.

At the end of their conversation, Dara asked Manucci if he wished to stay long in the Mughal territory. When he answered positively, the prince asked him to enter his service.

I replied that I should have put to very good use the weariness and fatigues of my journey if I had the good fortune to serve under so famous a prince.

The prince’s offer to enter his service as courtier and mercenary (quite a common role for Europeans in India at the time) provided for a monthly pay of eighty rupees (two point six rupees per day), a sarapa—‘which is a long strip of cloth, worn wound around one’s head in the shape of a turban, like the one donned by the Armenians in Europe’—a 300 rupees gratuity and a horse. Furthermore, Dara arranged for the faithful eunuch Khoja Miskin to stay by Manucci’s side, to watch over him.

The Mughals, one of the great dynasties in world history, dominated the Indian subcontinent for a period of around 350 years, from 1526 to 1858, although their decline had already begun in the eighteenth century. They were, from the beginning, a line of warriors who ‘ruled by the drawn sward’. Although they were great patrons in artistic, architectural, scientific and literary fields, their main characteristic was always their imperial ambition, as testified by the progressive expansion of their dominion. At its apogee, this covered an immense territory, from Afghanistan to Bangladesh and from Kashmir to Tamil Nadu. Their army’s excellence, therefore, was always decisive in determining their destiny. It became famous for its size. However, at the same time as it acquired size it also lost out in energy. In any case, in the seventeenth century, the Mughal army was one of the most powerful in the world, perhaps the most powerful.

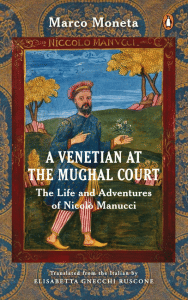

Marco Moneta holds a PhD in philosophy from Florence University. Elisabetta Gnecchi Ruscone is a social anthropologist.

This excerpt from ‘Venetian In Court: The Life and Adventures of Nicolò Manucci’ by Marco Moneta, translated from Italian by Elisabetta Gnecchi Ruscone, has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘Venetian In Court: The Life and Adventures of Nicolò Manucci’ by Marco Moneta, translated from Italian by Elisabetta Gnecchi Ruscone, has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.