At some point during his intense study of Indic thought, Dara Shukoh had a dream. We do not know the date or precise year, but we know that it happened during or before 1066 AH (1655/6). It was not a common sort of dream, because it was significant enough to be recorded. The prince had witnessed special visions before, ones that involved his spiritual guide Miyan Mir. Here, too, Dara’s dream evoked a longer history of Muslim rulers who had visionary dreams and Muslim authors whose dreams legitimized their literary projects.

Dreams of the Prophet Muhammad abound, like the vision that famously cured the blind poet Busiri of his blindness and led him to compose his celebrated Arabic ode on the mantle of the Prophet, the Qasidat-ul-burda, still recited today in countless commemorations of the Prophet’s birth. Learned men, too, could legitimize rulers through their appearances in dreams, like Aristotle, who materialized before the Abbasid caliph Mamun, as a rationale for the translation movement in Iraq. But Dara saw neither the Prophet nor an ancient Greek philosopher. He saw the Hindu sage Vasishtha along with the legendary prince Rama, believed to be the Hindu deity Vishnu descended on earth.

This dream was prompted by something the prince had recently read—a slim work of only a few handwritten pages. Its author was Dara’s contemporary Shaikh Sufi, who, as we remember, was a mystic and erstwhile Mughal official whom the Sufi writer Abd-ur-Rahman Chishti knew well and held in high regard. Shaikh Sufi claims that his book was a Persian translation of the Sanskrit Yogavasishtha, a work in the form of a dialogue between the legendary Rama, of Ramayana fame, and his teacher, Vasishtha. This dialogue is meant to have taken place while Rama was a young prince. The Persian text, as usual, follows the North Indian vernacular pronunciation of these names, which has Rama as “Ramchandra,” or “Ram” and Vasishtha as “Basisht.”

Also read: The Delhi prof who said tombs & mosques were not just ‘Muslim’, but ‘Indian Muslim’

The Jog Basisht (Yogavasishtha) that Dara Shukoh had in mind was not so much one text but a whole textual tradition. There are many versions and abridgments of this work: from the tenth-century monistic Mokshopaya, to the Yogavasishtha Maharamayana layered with Advaita Vedanta and Rama devotion, to the Laghu Yogavasishtha, a medieval abridgment of the latter by the Kashmiri scholar Abhinanda. The version that Shaikh Sufi’s text is based on, the Yogavasishthasara, is even briefer than the other works. In the longer texts, Basisht relates an interlocking series of stories to Ram, but this version omits the stories. Apart from the Mokshopaya, these texts share the basic narrative frame: the prince Ram had become weary of this world and wanted to withdraw from it, but Basisht gradually guided him toward spiritual liberation of a type that he could attain while still remaining a ruler. Dara Shukoh did not particularly care for the shaikh’s translation, but the figures of Ram and Basisht stayed with him long enough to penetrate his sleep.

Upon seeing Basisht, the prince said, he immediately prostrated himself before the sage. Basisht spoke. “O Ramchandra! This is a disciple who is absolutely sincere, please embrace him.”

“With the utmost affection, Ram took me into his arms,” Dara relates. “Thereafter, Basisht gave Ramchandra sweets to feed me with. I ate the sweets.”

Through words and actions, in the salutations and the giving of food, Basisht and Ram anointed Dara Shukoh as one of them, in much the same way that in his earlier visions, Miyan Mir imparted to him esoteric secrets heart-to-heart. But the prince saw Basisht and Ram as also ordaining him to perform an important task. The dream propelled Dara to carry out a translation project of his own. He would commission a translator to produce in Persian a new rendition of the Jog Basisht, one that was better than the version that Shaikh Sufi had made.

Also read: Art to sacrifices: How the horse became important in 18th century India

The prince leaves unmentioned the fact that previous Mughal rulers had also sponsored their own Persian renditions of the work. When his grandfather Jahangir was a prince, in 1597, he had the court litterateur Nizam Panipati collaborate with a couple of Sanskrit pandits to translate Abhinanda’s abridged Yogavasishtha into Persian. In 1602, Jahangir’s father, the emperor Akbar, had commissioned his own translation of the abridged Yogavasishtha, carried out by one Farmuli, who self-deprecatingly identifies himself as the lowliest disciple of the poet-saint Kabir. Gorgeously illustrated with forty-one miniatures, the manuscript survives today. It bears Shah Jahan’s imperial seal and inscription dating from 1627/8, the year he came to the throne. The prince must surely have had access to this prized holding of the imperial library. Why then would he need a new translation?

By translating the Laghu Yogavasishtha anew, Dara Shukoh claimed the text for himself. Its argument that a prince could achieve full self-realization as an ascetic while acting as an exemplary ruler spoke directly to his own situation. It also continued a link to previous imperial engagements with the text by Jahangir and Akbar, the prince’s grandfather and great-grandfather. Dara’s dream of anointment fits into a broader imperial ideology that presented the emperor as a spiritual and temporal master of the world in decidedly Indic terms. Translation in the Mughal context had often been a way of asserting imperial authority. To translate a text that had been in India far longer than one’s celebrated ancestors was to sprout deeper roots in the subcontinent’s soil. It was also a way to mold this earth in new ways.

The translator, who relates Dara Shukoh’s dream in his introduction, does not mention his own name. Some manuscripts identify him as an otherwise unknown Habibullah, though this could just be a case of mistaking a scribe for the author. If so, he would be an uncommon, though not unique, example of a Muslim man of letters who also possessed a high level of expertise in Sanskrit and religious thought.

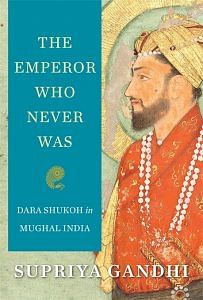

This excerpt from The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India by Supriya Gandhi has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.

This excerpt from The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India by Supriya Gandhi has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.

Life and travails of Dara is so scintillating and end so tragic that our new era generation should be exposed to. I hope, some well versed Bollywood directors/Actors/producers will look into this epic drama cum tragic story and make useful film to our subcontinent young generation.

Secularism begin with Dara shuko’s murder in India and happily continuing ever after.

Dara Shikoh was different from other princes . He influenced the mystic Sufism which believed in all religions r equal . Dream is integral part of Sufism . Interesting article about shikoh explore his personality .