Horses have decided the fate of empires.

In pre-colonial India, horses were used in wars, hunts and rituals. Horses were also the symbol of a ruler’s prestige. The mansabdar system during the Mughal rule – primarily under Akbar –institutionalised the use of horses. Rajput nobles would be given military positions according to the number of horses they had in their cavalry.

But it was in 18th century India when the importance of horses really showed – socially, culturally and politically.

After the Mughal empire started to decline, a number of regional kingdoms rose. As did the Maratha empire. At the same time, European colonisers were making inroads into the country. And horses became an important part of all these conquests.

Horses started showing up in paintings, manuals and even had their own portraits.

Also read: East India Company sent a diplomat to Jahangir & all the Mughal Emperor cared about was beer

In manuals

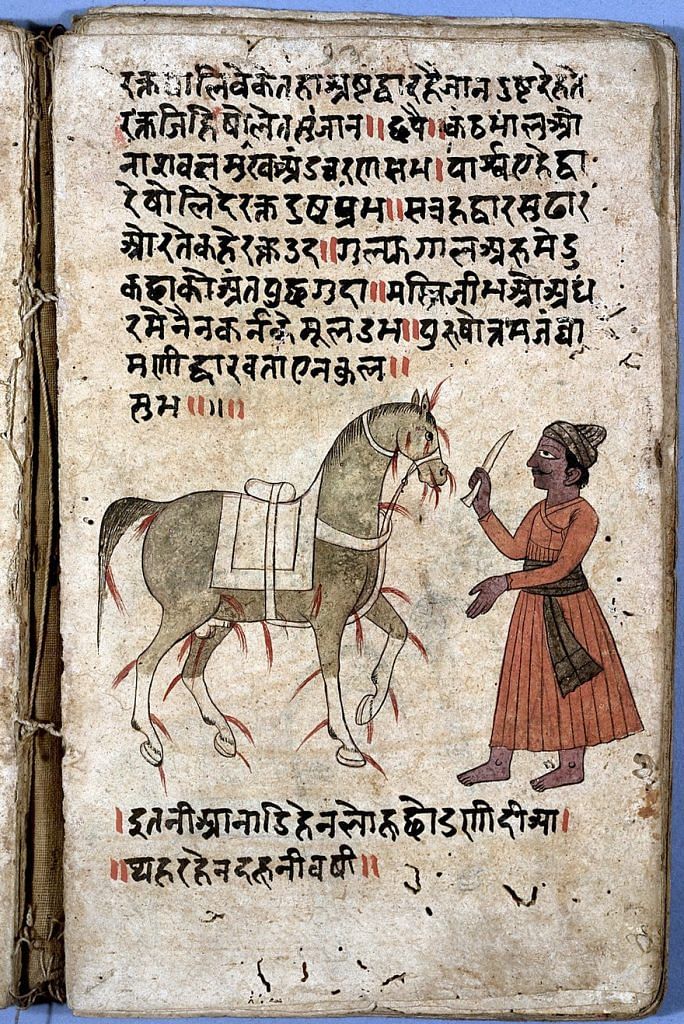

The increased demand in the 18th century for horses meant that a large number of people in the courts now needed knowledge on how to pick, keep and treat horses. The large number of copies of the horse manual called Shalihotra Samhita gathering dust in libraries today is the result of this high demand.

This 18th-century treatise described various breeds of horses, auspicious markings and colours that make a horse valuable, as well as equine diseases and treatments. The illustrations in these manuals suggest a primary visual horse vocabulary was being developed by the artists.

We tend to take horses for granted as props or background elements in paintings. But artists who illustrated these manuals needed to have considerable knowledge of horses. These animals were painted with great care.

It was important for horse owners and horse dealers to be able to judge the quality of a horse. The horse manuals came in handy. This equine knowledge system soon made its way into the Rajput courts. As art and architecture professor Vibhuti Sachdev points out, the paintings of horses produced in these courts depict the stylised likenesses of the real horses but also put in the features or markings that made horses auspicious.

Also read: How the golden era of Kathak began during the Mughal rule under Akbar

In portraits

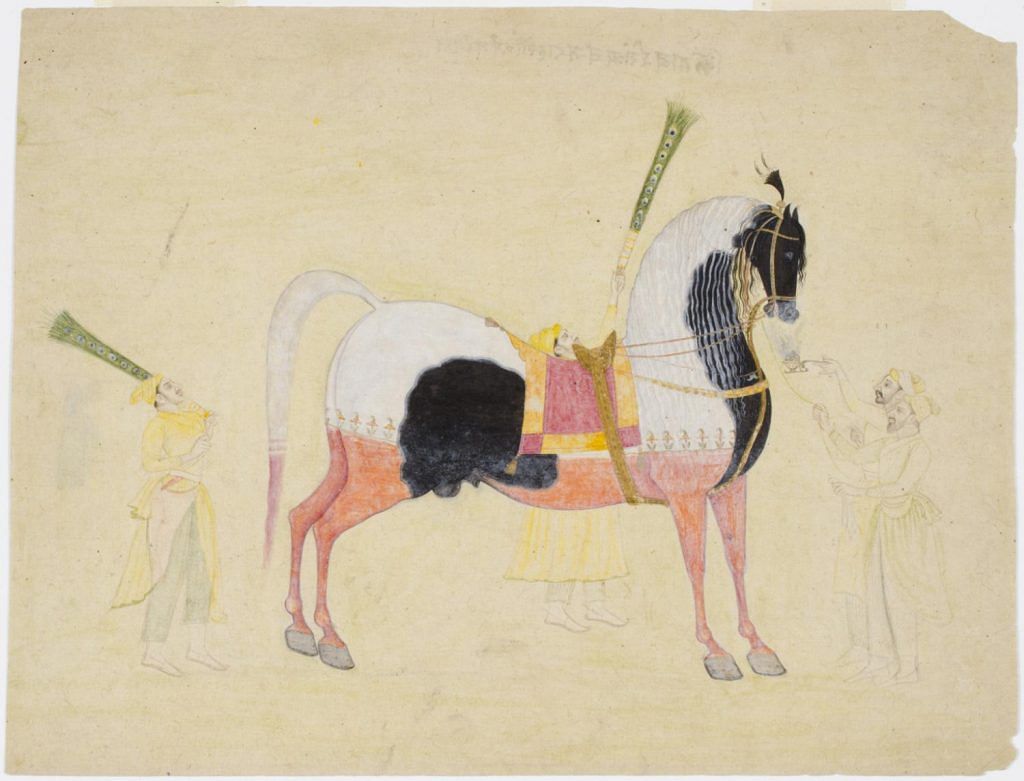

Now let us look at portraits of horses painted in the 18th century. In this painting from Kishangarh, artist Bhavanidas depicts a horse called ‘Kitab’. The two men standing in front of the horse seem to be worshipping it. True to Kishangarh portraiture, the horse is drawn in a highly stylised manner with exaggerated features and a highly arched back. Horses played a major role in winning a war and this made them worthy of veneration. In this painting, the artist has emphasised the horse’s importance by colouring it in full, while other figures are painted in the nim qalam style (literally meaning ‘half pen’, or lightly sketched). The prominence given to the horse is clearly a clue that it had its own political status in the court.

Some portraits give priority to horses over humans in other ways. This can be seen in the next painting whose inscription gives the name of the horse and not the rider. The name of the horse is ‘Yaar-Pyaro’ or a dear friend. The painter carefully depicts features mentioned in the Shalihotra Samhita as marks of a good horse, such as equal-sized teeth, which can be seen because the mouth is open, the different colours of the body and tail, and the size of the tail. Other features such as the shape of the eye, the shape of the ears, the arch of the neck and the gait of the horse, were all taken into consideration while painting this horse.

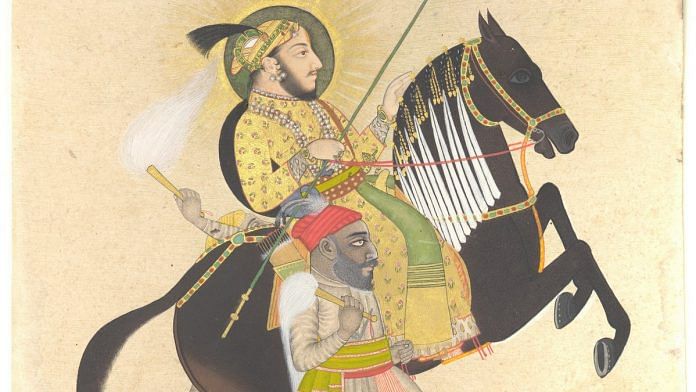

Horses were also considered divine animals. So, the image of the king as a horse-rider made him look authoritative and supreme. The equestrian portraits were valuable as ritual objects and were symbolic in nature, as Jagjeet Lally says, “absorbing all the symbolic power of their two subjects, the emperor and his horse.”

Interestingly, the equestrian portraits of Rajput rulers were made only after the Mughal empire began to decline. We do not see any equestrian portraits of the mansabdars being made by Mughal artists. Only in the 18th century did the break from the Mughals also give rise to an abundance of equestrian portraits of regional rulers.

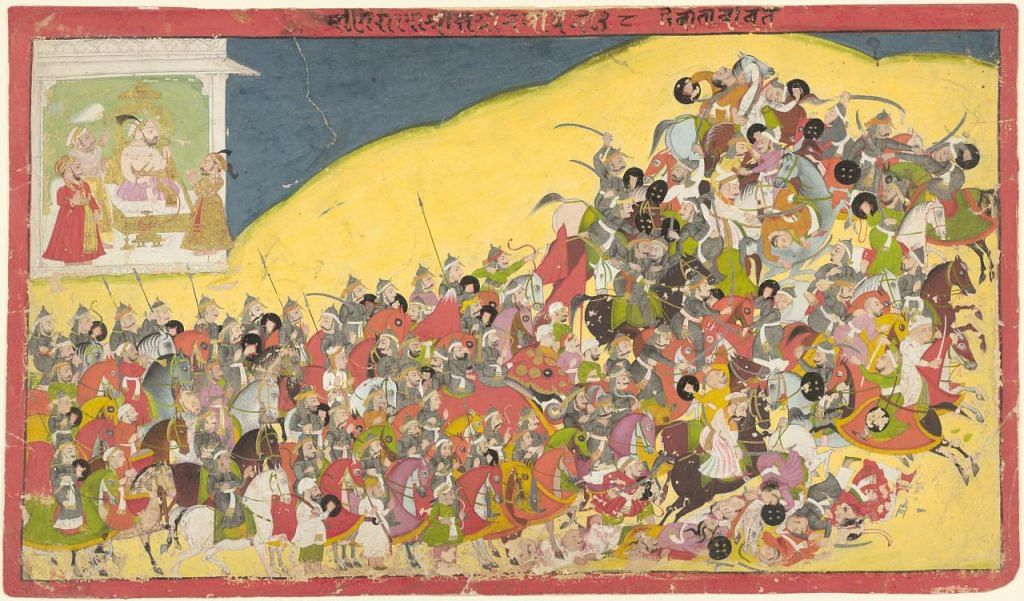

In action

The political use of horses can be best understood through war paintings of the 18th century. Just look at the position of the horses in these battlefield paintings. Even after the development of artillery, horses continued to be prominent in these works.

An important training ground for horses and the kings were during hunts. In most of these large hunting paintings, the king has the central position and he aims the arrow from the ‘right’ angle that will hit the target, unlike his soldiers; and his horse seems to be the perfect one in the entire act. The king often has a halo too, no doubt a product of Indian cultures mingling with the European ones in the 18th century.

Also read: Raja Ravi Varma, the royal artist who became part of daily life through calendar art

In sacrifices

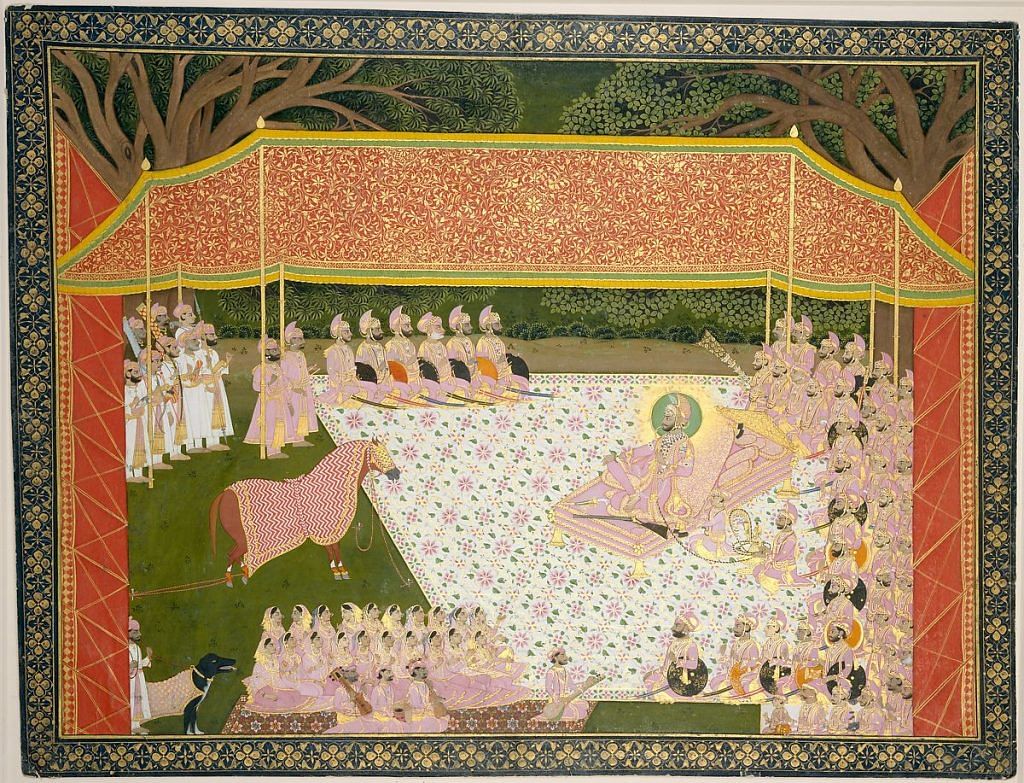

A number of rituals saw a revival in the 18th century, because Rajput rulers wanted to assert their legitimacy as dharmic kings and cultural crusaders. This included the ancient ashvamedha yagya – a horse sacrifice ritual. While Sawai Jai Singh II of Jaipur conducted such a yagya, his contemporary in Mewar, Sangram Singh II, had detailed rituals depicted in commissioned manuscripts. In the ashvamedha yagya, a white horse is left free to roam and the territory it covers is deemed to then belong to the king who sponsors the yagya. Anyone who stops the horse, in effect, challenges the king to battle. At the end of the ceremony, the queen ‘sleeps’ (symbolically) with the horse to ensure the fertility and prosperity of the kingdom, and the horse is finally sacrificed. The horse is then eaten by people of the court, including the Brahmin priest.

The great Mewar Ramayana painting commissioned by Sangram Singh II in 1712 includes an astounding depiction of this consumption of the sacrificed horse.

Although the Mughals considered horses as divine and commissioned many paintings, the various paintings from Rajput kingdoms give us a picture of the use of horses in the 18th century when their numbers increased.

At a time when catastrophic environmental damage is threatening the planet, these paintings help us remember a time when societies regarded animals carefully, and gave them as much attention as the humans that rode them.