In 2017, there used to be a television advertisement featuring Bollywood actor Ranbir Kapoor for Renault’s new SUV. The ad showcased the car rather well and did persuade me to go into the nearest showroom for a test drive. Noel used to be my natural ally for such showroom visits.

Accompanied by a courteous sales attendant, I embarked on the test drive, Noel in tow. In a few minutes, as I drove out onto the main road, Noel shot a question to the sales attendant, ‘Is there no CD player?’ He was attempting to turn up the volume, bending over from the back seat to reach the dashboard.

The sales attendant replied jovially, ‘This is a new-generation car, sir, only pen drive or mobile input! Listen to the sound, it’s fantastic!’

Noel did not appear happy with the explanation.

When we got back to the showroom for the usual sale discussions, the salesmen were pampering Noel, asking him which colour option would he prefer and generally behaving as if the sale was 99 per cent in their pocket and that the only thing left was Noel’s nod. With all the attention showered on him, Noel was feeling gleefully self-important. He was enjoying being addressed as ‘sir’ and being served coffee and biscuits with much pomp and cordiality. I had to haul him out of the showroom.

We started our drive home and Noel popped the question: ‘Why did you not buy the car?’

Wryly, I asked him what he thought was the reason. I always pushed him to string together the reasons in his mind and express himself with whatever vocabulary he had. In my head, I was readying the explanation of how the price was unjustified and how the key features fell short of other new SUVs.

Noel answered in a grim tone, ‘Because … because no CD player!’

For him, if one cannot insert physical music CDs into a stereo player, then there is not much sense in having a car, however swanky it may appear. The virtual space of ownership did not fit into his needs of the real. He needed to physically possess his favourite music titles only as CDs, feel them in his hands, title by title. Noel could listen to a single song a hundred times in a loop or have the same CD run again and again in the car music system.

Noel was drawn to music at a very early age. Even though he had not previously heard the words actually in usage per se, as he listened to songs, he would articulate the new words from the lyrics just as he heard them, word by word, in the exact tune. He never failed to get the tune right, not even the first time that he sang a song! It was astonishing and appeared to be a natural gift. Also, he was blessed with a good voice with considerable variation in pitch and the right baritone for melodic compositions.

When Noel was six, he started with Disney’s Children’s Favourites and they remained his favourites even when he turned twenty-six! They were his comfort music in times of loneliness or stress. He sang them all, from volumes 1-4, in the exact sequence as they appeared in the albums right through his childhood and adult years. Music worked like a balm beyond compare. It went beyond being a private, self-directed pacifier, opening a new door for social exchanges.

His first question would be ‘Do you have songs on your mobile phone?’ and if he had heard a song on that person’s mobile phone on an earlier occasion, then the next questions would follow: ‘Can I listen to Super Trouper by ABBA on your phone, please? After that, I want to listen to Thank You for the Music, please. What is your favourite song, friend? Can you sing it?’ and when the same question was posed to him, Noel would gladly oblige. Yes, he could instantaneously sing a song for you.

Then YouTube arrived, followed by the iPad which lit up his life like no other object. Music videos became a new and fascinating indulgence for Noel. He picked up and remembered every visual detail in the music videos. Also, he could watch a single video many times over. It was obviously a stimulatory experience and his innate trait of desiring repetitiveness was thoroughly indulged. His engagement with this sea of audio- visual enthrallment appeared to simply envelop him and he could be at it for five or six hours at a stretch. Also, my hunch was that he liked that a particular song is sung the same way every time it plays and the visuals sync with the track which fed unfailingly into the autistic appetite for sameness. The unchanging melody structure, the same musical instruments, the same pauses and effects, the same images in sequence brought him a certain calm and became the sure-shot resource to turn to whenever he used to get stressed and a tantrum was brewing or, on a more serious note, approaching a meltdown. No mood stabiliser medicines were required if music was at hand.

This inspired us to use songs to coach him in language skills, to describe situations he experienced and teach him the concept of one experience resembling another. We were cautiously optimistic that such techniques, along with adroit questioning, would lead to more articulate and expressive communications. Such unconventional methods of teaching became a matter of routine at home.

Noel’s love for music soon segued into an obsession with the game of antakshari (with Bollywood songs) when a friend, who also became his free-hand exercise instructor, introduced him to it. Once he had understood the ask, he became rather proficient and would traverse between Hindi and Bengali songs, playing antakshiri for hours.

Then a related development happened: when he heard a conversation going on near him that he was not part of, he would pluck a word from that conversation and sing a song starting with the exact word chosen. It was precise; the song just appeared on Noel’s lips automatically.

Singing as an expressive communication skill eventually reached a higher level: to express his opinion via a song or a segment of the song, he would invariably pick an apt one and sing aloud as a form of commentary on the situation at hand! On one instance, when our car braked and screeched to a halt to avoid a collision with an oncoming auto-rickshaw from the opposite side, Noel, sitting by my side, broke into an old classic from the ’70s, in full volume, ‘E! Bhai zara dekh key chalo, aagey bhi nahin, peechey bhi, dayine bhi nahin, baayen bhi … upar hi nahin, neecheybhi … e! Bhai zara dekh key chalo. (Hey! Bro, just watch a bit and move, not just in front, the rear side too, not just the right side, the left side also, not just what’s above you but also what’s beneath you)’. It was so whimsical to see him sing on cue!

There was a leap in his singing skills every year, particularly through his late teens and his memory for tunes and song lyrics. As he matured in the music department, many more amusing tales filled my treasure house of memories.

Noel had seated himself in the movie hall to watch his much-admired singer’s biopic, Rocketman. After about an hour of watching, humming and singing along, just when I began to think what a relief it was to see him in sync with everything and in a state of rare contentment, Noel stood up all of a sudden and announced, ‘I am finished.’ ‘The movie has not finished. Just sit down!’ said Ahvana sternly.

‘I am finished!’

Forcefully, he was made to sit. Then the answer came like a shaft of light in that darkness!

Noel, in tears, asked, ‘When will “Baby has got blue eyes, blue, blue day … and she is alone again … and I am home again” happen?’

Sir Elton John, the Rocketman, had disappointed him on that occasion!

Autism researcher, Pamela Heaton, Professor of Psychology, Goldsmiths University of London has shown that not just the savants, but even non-savant children with autism possess a great deal of musical potential that can be developed and channelised productively. Other researchers have observed that the affective quality of musical experiences is not muted in any way for the keen listener on the autism spectrum. In contrast to their performance within social and interpersonal domains, children with autistic disorders showed no deficits in processing the effect of musical stimuli*. It plays out differently for different people, but the overarching learning is that music must be a part of a child’s development plan. It can be imaginatively integrated into learning systems at home, at school, or at a work or training centre. It can be a steady therapeutic aid, as well as a crucial academic teaching aid; a vehicle for social interactions and social skill development. The magnitude of its value in enhancing the child’s inner sense of self-worth and self-confidence and, in the long run, providing eternal companionship, according to me, is beyond measure.

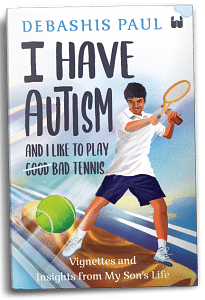

Extracted with permission from I HAVE AUTISM AND I LIKE TO PLAY GOOD BAD TENNIS by Debashis Paul, first published by Westland Non-Fiction, an imprint of Westland Books.

Extracted with permission from I HAVE AUTISM AND I LIKE TO PLAY GOOD BAD TENNIS by Debashis Paul, first published by Westland Non-Fiction, an imprint of Westland Books.