Revolutionary men with principles were not really different from the rest,’ reflects the protagonist in Woman at Point Zero, the novel by Egyptian feminist and psychiatrist Nawal El Saadawi. ‘They used their cleverness to get, in return for principles, what other men buy with their money.’

Occupied by foreign powers for decades, watching Iran’s sovereignty and wealth drained by their greed while at the same time being told they had inferior cultures and beliefs, Iranians (like so many in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa that century) were looking for a

way to be ‘modern’ without sacrificing their identities, without leaving behind what they saw as their histories and traditions. Before Ayatollah Khomeini came to power, people flocked to an influential and charismatic Paris-educated theologian who offered exactly

that.

Ali Shariati was in some ways the intellectual force behind the revolution, writes Zohreh Sullivan, a professor of english who has researched colonialism and the Iranian diaspora. Shariati’s call, she explains, was for a return ‘not to the self of a distant past, but a past that is present in the daily life of the people’. He preached against capitalist Western culture – but also in favour of science and industry. He adopted the language of the European Left, emphasising the struggle against imperialism and the need to redistribute wealth more fairly – but within an Islamic framework. He supported women’s equality with men to a degree – but denounced what he saw as female sexual exploitation in countries such as the United States.

This fresh, politicised brand of islam held genuine appeal for those who saw Western capitalism as using ‘women’s bodies to sell more commodities’, writes the historian Janet Afary. ‘Young women students began to wear the traditional Islamic headscarves and eagerly attended his sermons.’ Here was what looked to them like a culturally authentic, socially acceptable way to have agency and visibility within their faith. As many as 3,500 young people registered for a course of Shariati’s lectures in 1971, according to journalist James Buchan.

‘Shariati offered a vision of femininity – vigorous, loyal, chaste and companionable – that entranced many Iranian women.’ His was, adds Sullivan, a revolutionary model of Islamic womanhood.

Shariati died of a heart attack before the Iranian revolution began. Ayatollah Khomeini’s political convictions weren’t quite the same, but Khomeini did choose to pepper his speeches with the kind of language that Shariati had used. He spoke about ‘colonialism’, ‘exploitation’, and ‘social revolution’, explains Afary. Khomeini even mentioned the courage and independence of women. He told a reporter during the revolution that women would be ‘free in the Islamic republic in the selection of their activities and their future and their clothing’, adds Buchan.

This would turn out to be untrue, of course. Khomeini may well have known it was untrue as he said it. He had long been wedded to a particular vision of the respectable, devout Muslim woman. And he had consistently opposed reforms under the shah that favoured gender equality, including laws in the 1960s and 1970s to give women more divorce and child custody rights. But in its own way, the Islamic republic did try to reconcile religion with radicalism, and tradition with modernity. For all the other restrictions women and girls would face, the regime supported girls’ education and literacy. Segregating boys and girls reassured conservative families who were worried about sending their daughters away to study. eventually there would be no gender gap in university student numbers.

But there were tensions as well. ‘Our problems and miseries are caused by losing ourselves,’ Khomeini is quoted as once saying. The goal was to get Iran back to what it used to be. inevitably, this meant a focus on tradition and religion. And for women, this translated into an emphasis on their roles as wives and mothers.

‘Motherhood was politicized and valorized,’ writes Zohreh Sullivan. Birth rates shot up. Women’s employment rates plummeted under the islamic republic, especially in government jobs. Men’s employment rates rose. The effects of the state’s legal changes to

women’s and children’s rights have reverberated throughout the decades. in early 2021, the statistical center of Iran disclosed that there had been more than 9,000 child marriages registered in the country the previous summer, almost all of which involved girls

between the ages of ten and fourteen.

Not unlike in ancient Athens, the state’s integrity was invested in women’s bodies, its moral health seen to be reflected in their behaviour and dress. To be good Iranians, to truly reject foreign values, women needed to follow tradition. Even before Khomeini took power, this principle had become woven into how women behaved. At the height of the revolution, writes James Buchan, those who had never worn the black chador (a cloak that started to become customary in Iran from around the 1600s, loosely covering the whole body, exposing only the face, and held in place by hand) began to wear it to demonstrate their rejection of Western clothing and how much they identified with women in poorer and more rural areas who were more likely to veil.

The chador turned into a middle-class statement of solidarity with the working classes. This, in turn, was supported by the more religious and conservative elements in the revolutionary struggle against the shah, who had always wanted women to wear the veil. Chahla Chafiq recalls that during protest marches, ‘little by little, I saw groups of women in black chadors growing up and walking at a distance from the men. Then, one day, our group was visited by men who were circulating among the demonstrators, advising them to build non-mixed ranks. They also told us that it would be good to wear the veil anyway

to show that the people were united against the shah.’

Buchan writes that the shah’s twin sister, ashraf Pahlavi, who had played an active role in advancing women’s rights in Iran, watched crowds of demonstrators on the streets below from a helicopter during the revolution. She slowly realised that a moving black mass

below her was actually women wearing the dark chador, like the one her grandmother had worn. ‘My god,’ she thought, ‘is this how it ends?’

The fact that women fighting for equality and freedom would choose to wear the all-encompassing chador, once rejected by Iranian women’s rights activists, surprised onlookers not just outside Iran, but also some within it. By this stage, however, that piece of clothing did not represent what it had before. There were other forces at play. Now

the chador was associated not just with sexual modesty or religious devotion; it was also a visible marker of tradition. and at that moment tradition was a symbol of political resistance.

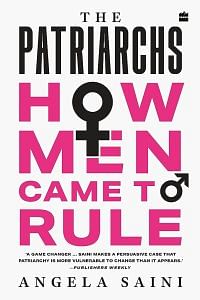

This excerpt from The Patriarchs by Angela Saini has been published with permission from Harper Collins.

This excerpt from The Patriarchs by Angela Saini has been published with permission from Harper Collins.