The book makes for a good history read but does little justice to the women of the Mughal era trapped by the male gaze.

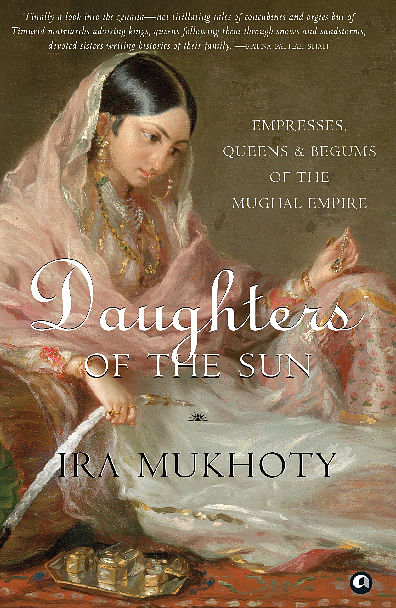

There is so much writing on the Mughal era but so little about the women who dominated lives of Babur, Humayun, Akbar and Shah Jahan.Women’s voices through history have remained elusive. Very little is known about their contributions in making history. This is what makes Daughters of the Sun by Ira Mukhoty, a book based on the women of the Mughal era so intriguing.

The book seeks to fill the loopholes in history, but does so in a limited way. It retraces the lives of the Mughal kings and their women, however, the stories of the latter remain hidden between the narratives of Mughal grandeur,which is of course, male-centric. If you are looking for juicy insights of romance between Akbar and his wives, then Bollywood will serve you better.

The book for a large part states the circumstances behind why the emperors married these women, the number of children they bore and how they felt after their beloveds died. Little is explained outside this blueprint. However, the author does spare a few exceptions and shines light on the likes of Maham Anaga, Akbar’s powerful foster mother, Gulbandan, Babur’s daughter and the first woman to have formally documented her father, and Jahanara, Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal’s daughter.

The fact that the book- a comment on the lives of these women- does not revolve around them, is curious.

The book’s impressive conversational narrative is not without its faults either. For example, the author refers to Hira Kunwar Sahiba Harkha as the first Rajput consort of Akbar without mentioning her popular name Jodha Bai. A simple overlook like this ends up making a reader feel less connected to these historical figures, and leaves them confused.

Much of the book’s information is credited to Mughal era biographies like Akbarnama, Tuzak-i-Baburi and Humayunnama. Naturally, these documents written by men provide only the male perspective, and the book struggles to get past this. At one point, it even mentions the meticulous way in which Akbar kept his women hidden, and controlled them inside his grand forts. Sadly, the matriarchal machinery behind the walls of these forts is only hinted and not explored.

The biggest takeaway from the book is the contributions of some of these women in creating Shahajanabad or old Delhi, a fact left out of most history books. Fourteen out of 19 grand structures in the city were built by the wives and daughters of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb

While these constructions remain forgotten, just the knowledge that these queens and princesses had the exchequer at their disposal over 400 years ago would be empowering for a woman reader.

The book makes for a good history read but does little justice to its title. The women of the era are still awaiting a voice to discover them properly.

COMMENTS