From the CBI versus V.C. Shukla case, better known as the Jain Hawala diaries case, of the early 90s to the Essar diaries of 2015, diaries have come to mean much more than simply some papers bunched together to keep note of important events and anniversaries.

The Jain Hawala diaries almost destroyed the careers of several Indian politicians across the political divide. In fact, it actually set back the careers of some very promising politicians by a few years, if not decades.

The main allegation was that between 1988 and 1991, the Jain brothers, allegedly involved in hawala operations – illegal laundering of money from India to abroad or vice versa – received unaccounted money and disbursed much of it among their relatives and public servants, including political leaders.

While the cases against politicians eventually collapsed in court, one good thing that came out of the entire case was that the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) got some amount of independence thereafter, following the judgment in Vineet Narain case, which was also linked to the Hawala case. The Central Vigilance Bureau (CVC) was also given statutory status through the landmark judgment by Justice J.S. Verma.

Also read: We’ll make 12 people ministers, give Rs 10 cr each — full transcript of Yeddyurappa clips

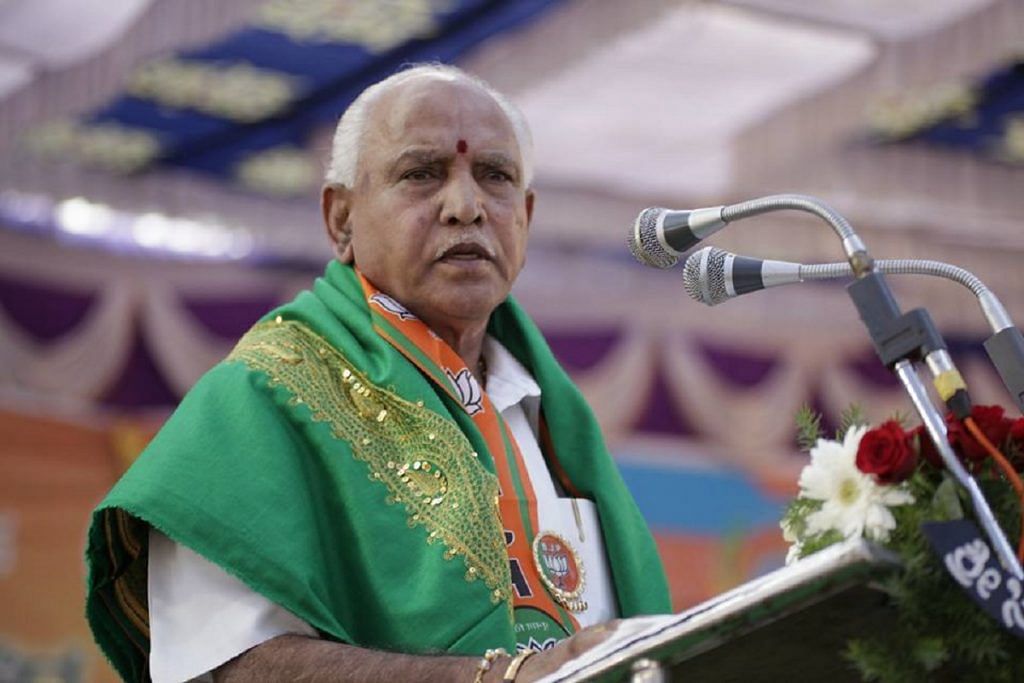

Twenty-two years later, however, even as the country witnessed political upheaval following the stinging disclosures – the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s claims and rebuttals notwithstanding – with the publication of pages that were purportedly part of a diary maintained by former Karnataka chief minister B.S. Yeddyurappa, in which there are references to money having been allegedly paid to top BJP leaders, there is a lot of grey area to the level of seriousness that can be assigned to such diaries, mainly recovered during raids by law enforcement agencies.

While the Supreme Court has made observations on the issue of whether entries in diaries, note-books or loose sheets of papers can form the basis of evidence in tax-evasion or other criminal cases, there is no clarity on which diaries can be part of evidence. Section 34 of the Evidence Act allows for submission of entries in ‘books of account’ but emphasises that these alone cannot be seen as sufficient evidence to charge the accused.

In the Jain Hawala diaries case, the Supreme Court held that without corroborating evidence, diaries cannot be evidence for convicting a person named in them. But, the same judgment also says that in cases where the diaries are properly maintained as per books of records, these are admissible as evidence.

But, then, shouldn’t the purported Yeddyurappa diaries be seriously investigated, since each page has allegedly been signed by the man himself? Shouldn’t some law enforcement agency be tasked with the job of verifying if the signatures are actually his or forged?

If hand-written entries in a notebook can’t be taken seriously, then what about something like entries in a laptop or a tablet?

Also read: In Karnataka, BJP’s Yeddyurappa runs two ‘dynasties’: politics and business

Since a lot of focus, especially of the courts, has been on corroborating evidence to prove that entries in a diary are actionable, whose job is it to find that corroborating evidence? Isn’t it too much to expect a whistleblower, in case there is one, providing a diary with information about payments made to some influential persons, to also provide the corroborating evidence? Why then have the plethora of investigating agencies? Moreover, if the presumption is that a whistleblower, or whosoever comes forward with such a diary, has forged its contents, can’t he similarly forge the corroborating material?

In 2017, the Supreme Court rejected a plea by NGO Common Cause for a court-monitored investigation into contents of documents and computer data recovered during raids on business establishments. The diary allegedly contained details of money paid to top politicians.

However, the Supreme Court ruled that entries in loose papers/sheets were irrelevant and inadmissible as evidence since such loose papers didn’t constitute “books of account”.

Now, isn’t it a bit naïve to assume that a person paying bribes to some of the most influential persons in the country will make entries in the company’s books of accounts? And what should be the standard and legally settled course of action if the entries in the diary have been made in an important person’s own hand – someone like, let’s say, Yeddyurappa.

Moreover, since the court has talked about the need for “independent evidence” to check the trustworthiness of entries in a diary, wouldn’t it be prudent to fix some responsibility on an investigating agency to which the complaint is made to at least make an effort to check the veracity of the diary entries or the claims made?

Also read: Feel like I’m being raped again & again, says Karnataka Speaker. MLAs have a hearty laugh

Wouldn’t this also ensure that there’s no embarrassment when names like those of Chief Vigilance Commissioner K.V. Chaudhary or Election Commissioner Sushil Chandra – both former chairpersons of the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) – crop up during press conferences about the diaries?

After all, it does make for an interesting coincidence that while Chaudhary was the CBDT chairperson when the agency looked into the Sahara-Birla diaries, Chandra was the board’s chief when the purported Yeddyurappa diary first came to light.

Time has possibly come for the courts to examine the entire issue concerning diaries afresh and settle the law governing their use so that no diary can be buried. At the same time, the courts must also ensure that unscrupulous elements are unable to use diaries to destroy careers of important public figures.