While the background of India’s Supreme Court judges has received attention, there has been almost no data on our High Court judges. Know Your High Court Judge – or KHOJ – seeks to fill that gap.

The KHOJ dataset was launched on 17 September at the National Law University Odisha by Chief Justice of India U.U. Lalit, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, Justice M.R. Shah and Orissa HC Chief Justice Dr S. Muralidhar. The dataset is now available on Justice Hub, an open-source platform for data related to the Indian justice system and accessible in a machine-readable format.

The dataset contains 27 files with 25 files dedicated to each High Court and includes personal, educational and professional information across 43 variables about all judges appointed between 6 October 1993 (since the inception of the collegium) and 31 May 2021. There is one integrated master file with details of 1,708 judges from all the High Courts where the name of each judge appears only once. In HC files, the name of a judge appears separately in the file of each High Court where she has served. There is a codebook that explains each of the 43 variables and the range of responses in relation to each variable in the dataset.

Also read: Indian judiciary is crying for basic infrastructure. Here’s what Centre & states need to do

Why do we need to know about our judges?

The core philosophy behind building such a dataset is that people of the country should have more information about judges whose decisions have a real impact on the lives of people. The continued capacity of the judiciary to function effectively rests on its capacity to generate public trust. As the organ with the least coercive powers at its disposal, the judiciary depends substantially on voluntary obedience from people for its decisions to be truly effective in society.

It is important to acknowledge that a veil of secrecy about how judges are appointed and who our judges is not conducive to generating or sustaining such trust.

What the dataset tells us

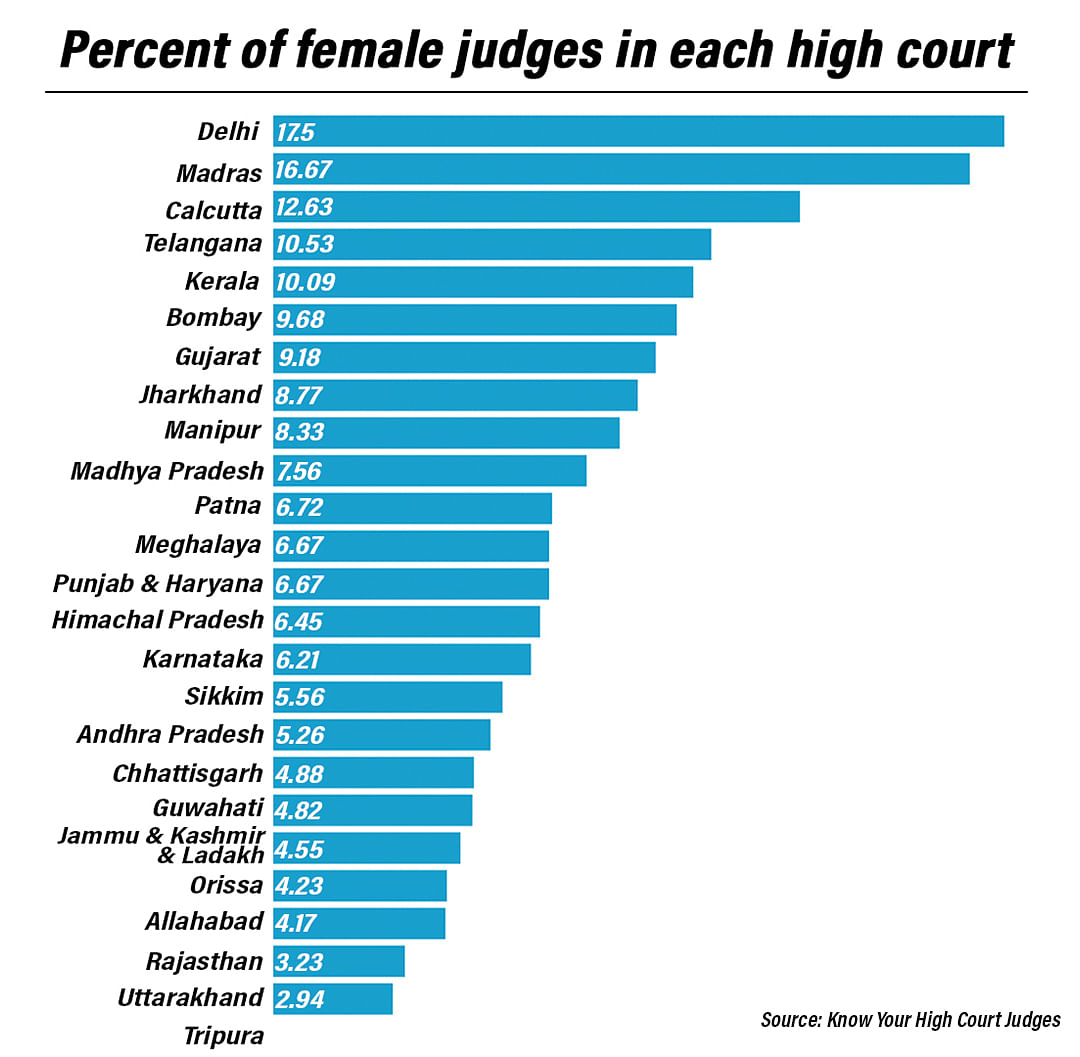

The KHOJ dataset reveals the privileges and marginalisation within the higher judiciary and brings to light patterns and trends that have been hiding in plain sight for all these years. For example, it reveals the extreme marginalisation of female judges and judges from the Service Cadre (those appointed as High Court judges from judicial officers in subordinate courts as distinguished from High Court judges appointed from lawyers). While judges from the Service Cadre constitute 43 per cent of all judges, they constitute only 4.46 per cent of all Chief Justices. When we look at the number of female judges as a percentage of all judges who have served in the High Court, not a single High Court breaches the 20 per cent threshold. In fact, only five High Courts breach the 10 per cent threshold (Delhi – 17.5 per cent, Madras – 16.67 per cent, Calcutta – 12.63 per cent, Telangana – 10.53 per cent, Kerala – 10.09 per cent). Of all the Chief Justices, only 7 per cent have been female.

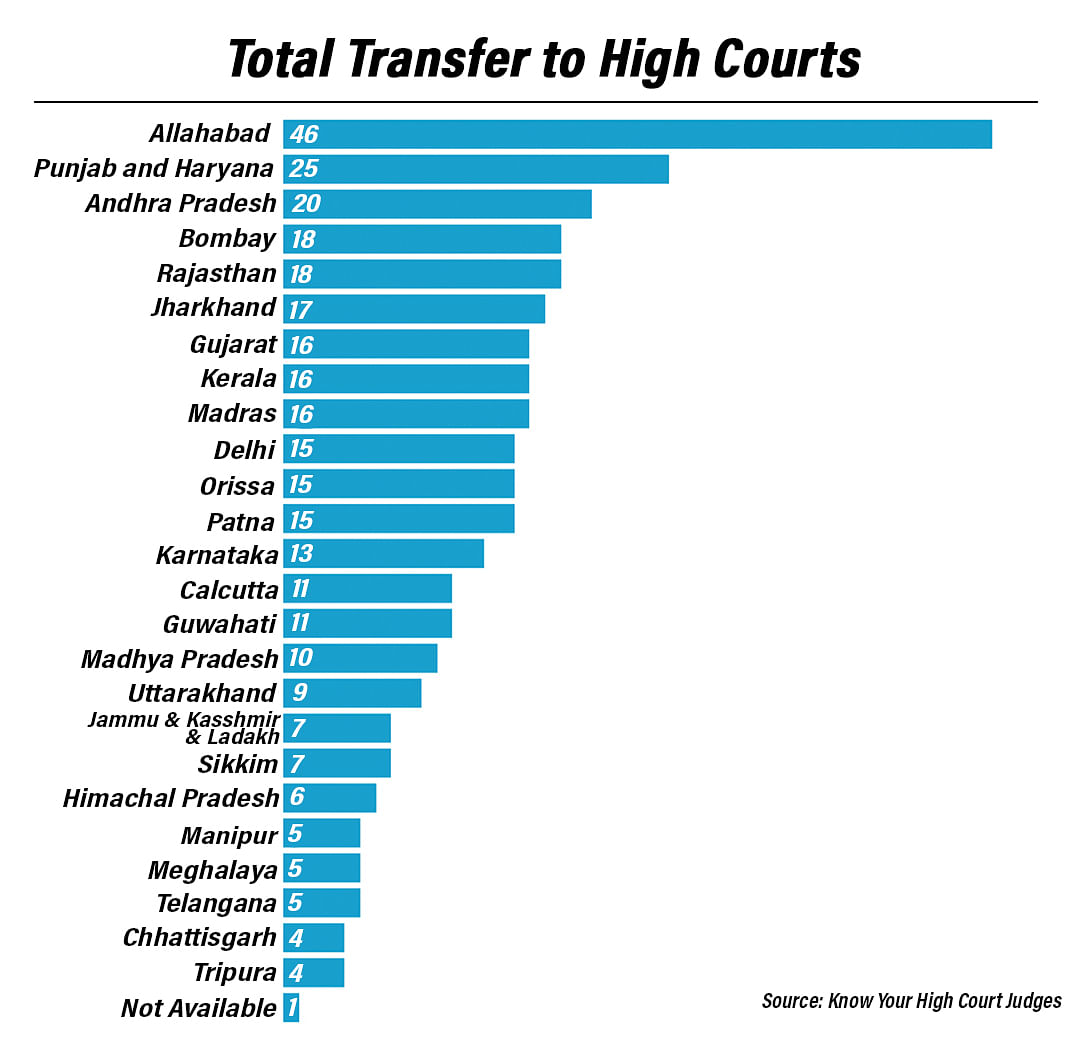

The dataset also reveals trends that require further probing. We have the first ever overview of the patterns of transfers of High Court judges. We have an overview of the number of judges who have been transferred and the number of times they have been transferred along with details of regional distribution of transfer patterns. For example, a total of 239 judges have been transferred, out of which 157 were transferred only once, 68 were transferred twice and 14 were transferred thrice. In terms of destination, the maximum number of judges have been transferred to Allahabad High Court and the least number of judges have been transferred to Tripura and Chhattisgarh High Court.

One of the most important things we learn from the dataset is the extent to which information is not available about judges in openly accessible public sources. The dataset has a total of 73,444 data points (1,708 judges and 43 variables). There are some data points that are ‘not applicable’ for a judge. For example, for a judge without any experience in the subordinate judiciary, all corresponding entries in ‘High Court Administrative Experience’ will be tagged as ‘not applicable’. There are a total of 17,490 data points that have been marked as ‘not applicable’. Then if we exclude some very rudimentary data points (name, gender, date of appointment etc.), we are left with 51,130 data points. Of these, no data was available in relation to 31 per cent of the data points. In fact, 147 judges had to be excluded from the dataset because their data of appointment is not available and there was no other way to verify if they were appointed before 6 October 1993.

However, ‘non-availability’ of data is not uniform across variables. There are several gaps in the information provided. For example, for 1,202 judges, there is no information available about their place of birth. But the year of birth is not available for only 106 judges. There are 90 judges in relation to whom there is no information about their cadre (Service/Bar). The most significant non-availability of data is in relation to educational and professional details. Out of 1,374 judges who have had litigation experience in their career, 94 per cent of them do not share any detail about any private companies they might have served. Similarly, in relation to 84 per cent of judges with litigation experience, we do not have any data regarding the Chambers they were attached to. For 42 per cent of judges, there is no data about the institution from which they got their qualifying law degree. For 59 per cent of judges, there is no data about the year in which they got their qualifying law degree.

Also read: Modi govt will have to wait on All India Judicial Services. Top judiciary main opposition

A community approach to legal data

The logistics of the data collection exercise was managed by Agami along with CivicDataLab and the Centre for Public Policy, Law and Good Governance (National Law University, Odisha). It started with the ‘Summer of Data 2021’ programme where 37 law students from across the country volunteered to co-create the dataset using official and publicly accessible data sources. Then, the dataset went through several rounds of cleaning and verification.

It was a conscious decision to not rely on a small team of selected and known individuals. So, the Summer of Data programme invited volunteers from across the country. The purpose was not simply to create a dataset but to engage more people with the experience of dataset creation and interact with the legal system from a fresh perspective. Since there is a scarcity of collated and structured datasets in the legal and justice sphere, KHOJ was created openly in order to reduce duplicity of efforts by researchers in the future. The idea was not simply to deliver a dataset to people but to have a community of people experience the creation of it and consequentially trigger a sense of public ownership of this digital good.

There were two key challenges with community curation of such a massive dataset. First, the information available on judges is quite diffused on the internet across all kinds of sources. Second, to ensure the consistency and quality of the data, multiple rounds of verification, cleaning and standardisation had to be undertaken. In addition to the student volunteers, experts from TresVista, a leading financial outsourcing firm, also provided technical assistance to plug any remaining gaps. Finally, a small team of fact-checkers validated each data point to the extent possible.

Also read: How can landmark laws fail? Just look at how high courts resist RTI

Legal data as public good

We believe that everyone should have equal opportunity to access and understand the legal system and be able to contribute to its evolution. We acknowledge the potential that openly available legal data holds in igniting the agency within each one of us to not just seek, but make justice a reality for ourselves.

So, the dataset has not been designed with the purpose of being fossilised as the backbone of a pay-walled journal article. KHOJ has been created to enable others to build on it and if possible, fill in the gaps. It is based on the realisation that many people are trying to understand the judicial system, but most are operating in silos. KHOJ is an effort to transcend the silos by making critical data openly accessible to all. This effort is based on the belief that legal data is a ‘public good’ that should be freely available to everybody to use.

Rangin Pallav is Professor of Law at National Law University, and Director, Centre for Public Policy, Law and Good Governance. Saurabh Karn is Curator at Agami and Co-Lead, OpenNyAI. Apoorv Anand is a Data Strategist at CivicDataLab. Smita Gupta is Weaver at Agami and Co-Lead, OpenNyAI. Views are personal.