The state of a court’s infrastructure can have a massive impact on the dispensation of justice. For example, a well-designed and adequately equipped courtroom can help enhance the productivity of a sitting judge; it is also true for lawyers and their chambers, when preparing for their cases. Expressing his concern at the slow progress in infrastructure projects at the district and subordinate courts, Chief Justice of India N.V. Ramana remarked in October 2021: “Good judicial infrastructure for courts in India has always been an afterthought. It is because of this mindset that courts still operate from dilapidated structures making it difficult to effectively perform their functions.”

Yet, Ramana is not the first CJI to have flagged this. In 2016, then-CJI T.S. Thakur became visibly upset as he stated a long list of backlogs, judicial vacancies, and infrastructure woes impacting justice delivery and judicial credibility. Such delays in the movement of cases disproportionately affects the poor and marginalised, who do not have the financial means nor the social and political connections to endure the lengths required to see their cases through.

The positive correlation between availability of judicial infrastructure and justice delivery is empirically well-established. According to the National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms, adequate judicial infrastructure is a prerequisite for reducing delays in cases. The National Court Management System (NCMS), constituted by the Supreme Court, found a direct connection between physical infrastructure, personnel strength, and digital infrastructure, and pendency. Indeed, statistics show that India’s subordinate judiciary struggles with pendency due to an acute shortage of courtrooms, secretarial and support staff, and residential accommodation for judges.

In early 2020, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic made it even more clear that infrastructure, particularly digital, is key to the functioning of the judicial system. Courts were forced to conduct their business in virtual mode, but with only one-third of the lower courts having proper digital facilities (including a computer at the judge’s dais, with video-conferencing facility), justice delivery suffered a blow. The pandemic-induced disruptions since March 2020 have pushed the pendency of cases to 19 percent, taking it to a record 4.4 crore.

Also read: Judges need to focus on cases, not HR, procurement and finance. The NJIC is good idea

Physical infrastructure

According to data from the National Judicial Data Grid, the sanctioned strength of judges in India is 24,280. At present, however, there are only 20,143 court halls available, of which 620 are rented. The number of halls under construction is 2,423.

Meanwhile, there are only 17,800 residential units available for the judicial officers, of which 3,988 are rented. A measly 2 percent of the lower and subordinate courts provide tactile pathways for the visually impaired, 20 percent have guide maps, and 45 percent have help desks. Further, a large 68 percent of lower courts do not have dedicated rooms for record-keeping, and nearly half of them do not have a library.

An essential hard infrastructure is ease of accessibility via public transport. According to an in-depth report by the legal think tank Vidhi, a majority of lower court complexes in Gujarat, Sikkim, and Tripura are not accessible through public transport.

The same report on district and subordinate courts found that less than half of the courtrooms surveyed (40 percent or 266 out of 665 court complexes) had fully functioning washrooms. Only slightly more than half (354 out of 665 court complexes) have a washroom on every floor. More notable is that 26 percent of the district courts have no running water in the women’s washrooms, and a low 11 percent of the washrooms are accessible for those with disabilities.

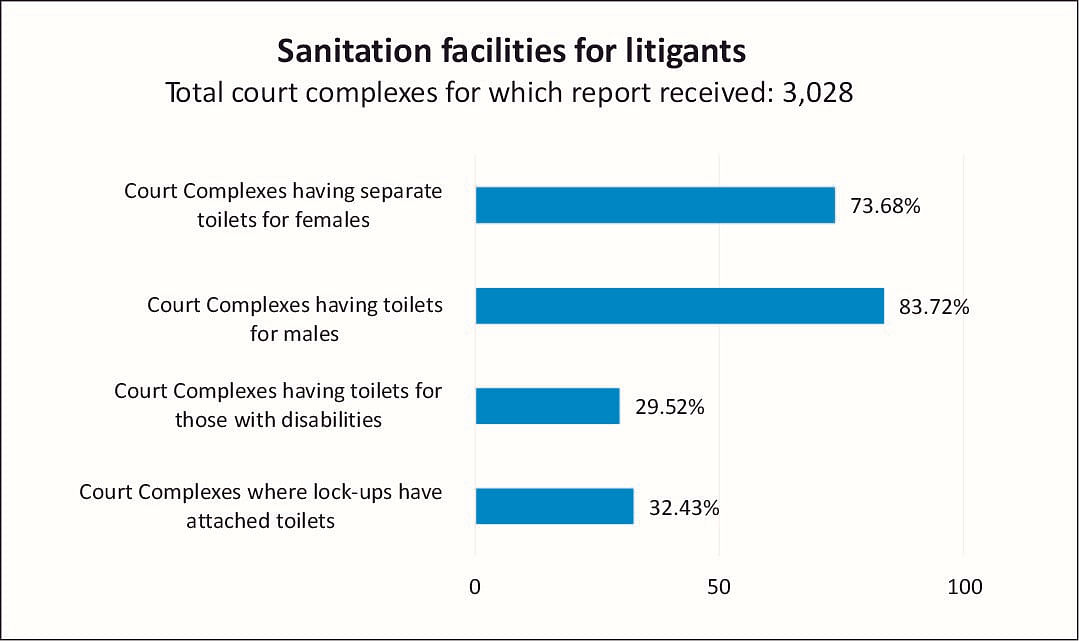

A similar study undertaken by the CJI’s office in 2021, covering a bigger number of court complexes (3,028), found that less than 30 percent of them had washrooms accessible for people with disabilities (Figure 1). Goa, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Mizoram had the lowest percentage of court complexes with functional washrooms. None of the court complexes in Goa had fully functional washrooms, and there was no provision for running water or for regular cleaning. In Jharkhand, only two out of 24 court complexes (8 percent) were fully functional; in Uttar Pradesh, eight out of 74 court complexes or 11 percent, and in Mizoram, one out of eight court complexes, or 13 percent, had fully functioning washrooms.

Figure 1. Sanitation facilities in India’s lower courts

Also read: India needs National Technology Coordinator. An Indian model in digital infrastructure is ready

Digital Infrastructure

Digital infrastructure not only helps litigants access their hearings (in the event of online proceedings) but also ensures that relevant information about cases, and the judges presiding over them, is accessible to the public. The lack of these critical infrastructures proved to be a big hurdle during the Covid-19 pandemic when courts were forced to go virtual. With only 27 percent of subordinate courts being able to place a computer with a video-conferencing facility at the judge’s dais, justice delivery suffered.

The 2019 Vidhi report found that around 89 percent of the lower courts’ websites upload case lists, case orders, and case status. However, only 36 percent of the websites featured court maps, and an even lower 32 percent listed the names of judges on leave.

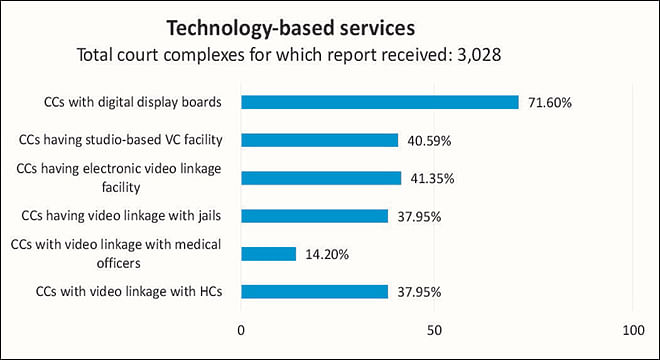

Meanwhile, according to the 2021 survey by the CJI office, nearly 72 percent of lower court complexes had digital display boards, and only 41 percent of them had a studio-based video conferencing facility. The same survey found only 38 percent of lower court complexes had video linkages with jails, and 14 percent had video linkages with medical officers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Technological facilities in India’s lower courts

Also read: India must build, re-build its courts for disabled. Judicial infra key to justice delivery

Central scheme for judicial infrastructure

The Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) for Development of Infrastructure Facilities for Districts and Subordinate Judiciary was set up in 1993-94. The scheme was devised to meet the country’s expanding justice delivery needs following economic liberalisation in 1991.

Planned and operated by the Department of Justice under the Union Ministry of Law and Justice, the scheme mandated the provision of financial assistance by the Centre to the states and Union Territories (UTs) for the construction of court halls and residential units for judicial officers and judges of the district and subordinate courts. The funding plan uses a ratio of 60:40 between the Centre and the state; 90:10 for Northeastern and Himalayan states and 100 percent central funding for the UTs.

From 1993 to 2020, the Centre allotted Rs 7,460 crore to the states and UTs. The Union Cabinet made the decision to extend the scheme for five more years (2021-26) with a financial commitment of Rs 5,357 crore. However, the infrastructure gaps at the district and lower levels of the judiciary remain a matter of grave concern. The central scheme is mired in multiple challenges.

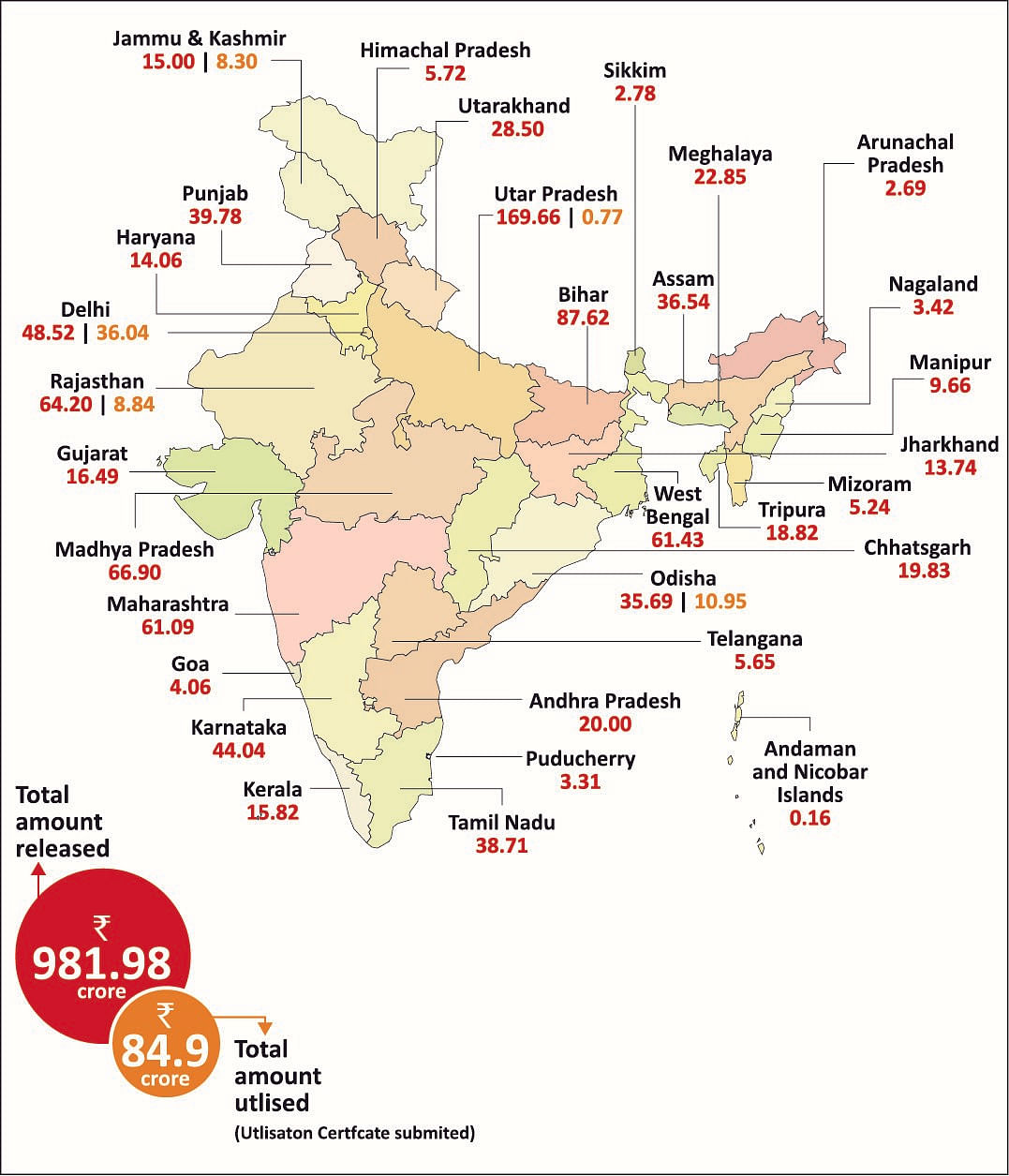

Figure 3. CSS funds, by state and UT (2019-20, in Rs crore)

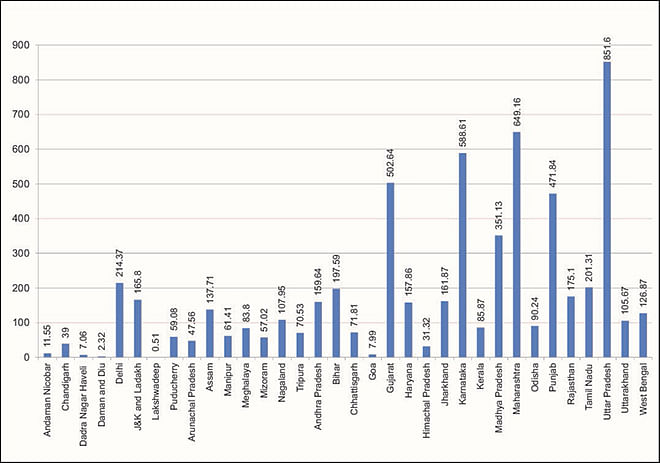

Figure 4. Central funds for CSS, 1993-94 to 2018-19 (in Rs crore)

Also read: Recipe of India’s broken justice system — 4 mealworms in turmeric, 38 years, Supreme Court

Enduring obstacles

The CSS could do more if it can hurdle the roadblocks that slow it down.

A key obstacle is erratic financing. Between 1993-94 and 1996-97, the central allocation for the scheme was a meagre Rs 180 crore under the 8th Five-Year Plan. While there was a slight increase in the subsequent period, by the end of 2011, the central allocation was only Rs 1,245 crore. The yearly funding averaged Rs 69.18 crore per year for all states and UTs.

In 2011-12, the central scheme received a modest increase in allocations under the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, to Rs 595.74 crore. Consequently, every year from 2011, the Central government released an average of Rs 693 crore to the states and UTs. The infusion by the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government of funds amounting to Rs 9,000 crore (including 40 percent contribution from states) might just help speed up the judicial infrastructural development.

However, financing alone is not enough, and the more difficult challenge is the lack of enthusiasm from the states. This is evident in the non-utilisation of funds, the allocation for which eventually lapsed. In 2019-20, for example, as much as 91 percent of CSS funds were unused: of the Rs 981.98 crore allocated to the states, only Rs 84.9 crore was spent by five states.

There are many reasons why CSS funds are underutilised, and the first one is related to the states’ financial condition. The CSS requires states to match 40 percent of the grant from the central government; most states have routinely failed to fulfil this commitment. As a result, the allocated funds either go unspent or they lapse. Studies have also found that certain states have diverted funds meant for judicial infrastructure to other projects. A third hurdle is the poor coordination among multiple authorities. For instance, in Kerala, a trial court complex project in the district of Idukki that has been ongoing since 1997 has remained unfinished owing to bureaucratic red-tape and institutional lethargy.

It has not helped that the CSS puts a low premium on transparency and accountability. To begin with, there are no explanations as to why certain states receive more funds than others. There is hardly any data in the public domain to monitor the utilisation of funds. According to a review by Vidhi, information on how many courtrooms have been built via the central scheme are not available to the public. Further, while the scheme has in-built mechanisms such as the presence of monitoring committees at the district, state and central levels, their reports, if any, are not made public. After decades, the Department of Justice in 2018 engaged an agency to evaluate the scheme; the report put the blame largely on the states.

Finally, as underlined in the Vidhi report, there are communication gaps between the Centre and states, adding to inefficiency. The Centre releases its share based on the funds available and expects the states to contribute the remaining share, depending on the prevailing ratio at the time. However, most state governments seem to presume that the Centre will allocate its share in consideration of the requirement projected by the state in its action plan. This confusion is evident in the correspondence between the Department of Justice and the state governments, as reported by Vidhi. While the CSS, therefore, may have had a clear vision, and successive central governments have allocated significant funds for it, its faulty design and the lack of interest and ownership from the states hobble its effectiveness.

Also read: How can landmark laws fail? Just look at how high courts resist RTI

Missing key: Institutional attention

Beyond the central scheme and its limitations, the infrastructural crisis at the judiciary must be seen in the context of political apathy in bringing the necessary transformation of a key arm of government. The historical neglect of the judiciary, as CJI Ramana put it, has resulted in inadequate institutional attention to these glaring gaps that impact the delivery of justice especially to the poor. This is evident in the budgetary allocations to the judicial branch. More than seven decades since Independence, the budgetary allocations for the judiciary (including the contributions from the states) still fall far below 1 percent of GDP.

Between 2011-12 and 2015-2016, India’s annual average spending on the judiciary was a measly 0.08 percent of GDP. While this has slightly improved with the Centre increasing allocations under the 13th and 14th Finance Commissions, it remains an area of serious concern. Furthermore, the allocation from the Union Budget for the judiciary also remains inadequate and inconsistent. For instance, at a time when pendency of cases has grown exponentially and judicial infrastructure is unable to keep pace with the pressures on the dockets, there was a steep cut in the 2019-20 Union budget in funds for judicial infrastructure, from an earlier Rs 990 crore to Rs 762 crore.

At the same time, the states have shown a largely lukewarm response to this critical need, as seen as well in their own budgetary allocations. For instance, states have allocated less than 2 percent of their cumulative budgets to judicial infrastructure; the exception is Maharashtra, which sanctions 2 percent. A silver lining could be gleaned, though, from a report by DAKSH and the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA): While the combined expenditure by the central and state governments on the judiciary increased by as much as 53 percent between 2016-17 and 2018-19, on ground, the states had contributed as much as 92 percent of this allocation.

Also read: Corona is a wake up call for Indian courts. They aren’t equipped to function in a crisis

Recommendations and conclusion

In 2021, Justice Ramana had proposed the setting up of a National Judicial Infrastructure Corporation (NJIC), which can monitor and act on the perennial issues of delay in land allotment, funds diversion for non-judicial purposes, and evasion of responsibilities by the high courts and trial courts among others. The NJIC—which would comprise the CJI, judges of the Supreme Court and high courts, finance secretaries of the Centre and states concerned—can put an end to the bureaucratic hurdles and challenges in coordination.

However, analysts have raised doubts whether such a central agency is required at this juncture. These observers caution that the centralisation of powers under a new body would only go against the principles of federalism, and that an NJIC cannot force states to spend more or concede powers to the proposed body. Moreover, infrastructure projects, particularly under CSS funding, have tedious processes involving considerable paperwork between the Centre and states. There are issues of coordination on land acquisition, tendering, and awarding of contracts, as well as site inspections. This would require time and effort on the part of NJIC.

Given that judicial infrastructure in the lower courts is a complex federal issue, some alternative ideas are worth pondering.

First, the real challenge in infrastructure growth is not lack of funds, but rather clearing the federal hurdles particularly getting the respective states to own the programme. This can be addressed if the Department of Justice can show the required leadership by increasing its interactions with state-level officers to ensure timely implementation of the central scheme. It would be in the interest of justice if the DoJ shuns the culture of unilateral decision-making by taking states on board with regards to budgeted demand for judicial infrastructure. This is because the quantum of allocation to the states are arbitrarily determined by the DoJ. The asymmetrical distribution of funds between states is an issue that has been repeatedly identified even by Parliamentary Standing Committees. Making states equal partners can help build their sense of ownership for the central scheme.

Second, a large percentage of CSS funds remains unspent year after year due to the inflexibility in CSS guidelines that constrains state governments to spend on other infrastructure-related items. This was complicated by the 2021 CSS guidelines that give priority to construction of court halls and residential complexes over other projects. NITI Aayog’s Guidelines for Flexi-Funds—which allows states to spend CSS funds in a more flexible manner up to a certain percentage—could be an answer to the prolonged under-utilisation of funds meant for judicial infrastructure.

Third, rather than having one NJIC, the DoJ can decentralise and clear lines of hierarchy where implementation of the central scheme for judicial infrastructure can happen at the level of high courts. One way of maintaining accountability is by mandating timely updates for websites of the high and subordinate courts; this can ensure that transparent mechanisms are accessible to the public to check the status of infrastructure projects. Further, greater accessibility by civil society can increase accountability.

Fourth, the central scheme’s effectiveness can be strengthened by having a timely performance audit of the utilisation of funds meant for infrastructure projects. Additionally, it is recommended that a thorough audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) on the financial and material performance of the scheme be undertaken before giving extension to the scheme. The yearly audits also need to be published at regular intervals to show where the funds are being allocated.

Finally, the improvement of infrastructure at the lower judiciary should move beyond quantitative aspects. Building more courtrooms and residential complexes should not come at the cost of quality and other key parameters. The basic parameters that have been laid down by the National Court Management Systems Committee, such as navigation, ease of reaching the court, waiting areas, barrier-free access, availability of case displays, security, amenities and toilets, among others, must be strictly adhered to while constructing court complexes. There should also be simultaneous efforts to modernise the existing courtrooms and equip them with better technology.

Given its broader vision of social justice, the judiciary and the judicial services are a non-negotiable sovereign function which only the State can provide.

The imperative is for an overhaul in the existing central scheme, where the DoJ should be playing the anchor’s role in getting the states and related institutions onboard. The strategy and tools employed by the Centre in making some of the central flagship schemes succeed can and should earnestly be applied in this domain.

Niranjan Sahoo, PhD, is a Senior Fellow with ORF’s Governance and Politics Initiative.

Jibran A Khan is a graduate of Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, Lucknow, and an Associate with PLR Chambers, Delhi.

This is an edited excerpt from the authors’ report — “Improving India’s Justice Delivery System: Why Infrastructure Matters” — published in ORF Issue Brief No. 562, July 2022, Observer Research Foundation.