Delhi has long had a difficult relationship with its lush Punjab hinterland. The land has seen the coming and going of many conquerors, from the Kushans, Huns, and Turks to the Mongols, Mughals, and Afghans. In more recent decades, Punjab has challenged Delhi as it once challenged Mughal emperors. As the state heads toward elections in a few weeks, here’s how Sikh farmers toppled an empire—for the first but not the last time.

The legacy of the gurus

Like many communities in North India, the history of the Sikhs begins with the Mughals (for better and for worse). In the mid-to-late 16th century, the bureaucracy of the emperor Akbar, composed substantially of Banias, Rajputs, and Brahmins, brought agrarian expansion to new frontiers. Trade links to Central Asia were revitalised and safeguarded. Encouraged by this stability, nomadic groups in Punjab settled down, and many local chiefs accepted the status of Mughal zamindars.

These Punjabi chiefs were an ethnically and religiously diverse lot, as historian Jos JL Gommans writes in The Rise of the Indo-Afghan Empire, c. 1710–1780. Think of it as a massive pyramid. At the bottom were Jat peasants who followed a variety of popular practices, Brahminical and Sufi. Above them were Manj Rajputs, Qasur Afghans, and Banjara and Khatri traders. Mughal governors at the top of the pyramid were probably of Uzbek, Persian, or Indian descent. Every group had a notion of its status in relation to others and the rituals that set them apart. Mughal emperors provided all these martial people with prestige, employment, and loot. This bound them directly to the Mughal state in a delicate balance.

In the 17th century, if you told any of these powerful groups that Sikhs would one day dominate Punjab, you would be laughed out of the bazaar. The Sikhs were, relatively speaking, nobodies. They challenged the notion of caste purity and rituals, which, by today’s standards, was akin to saying the earth was flat. They were also monotheists, denying the authority of Hindu gods. The early gurus were spiritual leaders, avoiding any claims to political authority. As long as they did so—according to imperial memoirs like the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri—they were tolerated by the Mughal state.

According to the emperor Jahangir’s own account, a relatively minor act led to mounting disaster in the Punjab. One of the Sikh Gurus, Arjan Singh, offered a saffron forehead mark to the emperor’s rebellious son. The Mughal state, paranoid at the best of times, responded with violence. The Guru’s property was confiscated, and he was executed. But this only brought more attention to the Sikh Gurus, and they now began to claim both moral superiority and political autonomy. This, in turn, brought worse Mughal reprisals. Before his assassination in 1708, the last Guru, Gobind Singh, possessed all the trappings of an early modern lord: a court, poets, and armed retainers. It was through this armed group—the Khalsa—that Sikh power would grow and explode.

Also read: How a fading Benares dynasty commissioned North India’s greatest Ramayana paintings

From the Gurus to the Jat chieftains

When Gobind Singh died, Sikhs, like the rest of Punjab, were a diverse lot. As historian Purnima Dhawan writes in When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699–1799, the armed Khalsa were a minority within a minority—never more than 10 per cent of Punjab’s population. Their early texts stressed the superiority of Sikh teachings and emphasised Khalsa identity over caste and clan. They criticised Hindu gurus and rival Sikh groups. This was not a winning strategy in the clannish world of 18th-century Punjab.

The rise of the Khalsa involved major innovations as well as fumbles from their rivals. The Mughal state, eternally short-sighted, tried to brand attacks on the Khalsa as a “jihad”, trying to mobilise Punjabi-Afghan zamindars. The Khalsa, in retaliation, reinvented the older Sikh concept of “dharamyudh”, religious war against the Mughal state. Originally thought of as an internal struggle, this new formulation had many more takers—especially among Punjab’s Jat peasants.

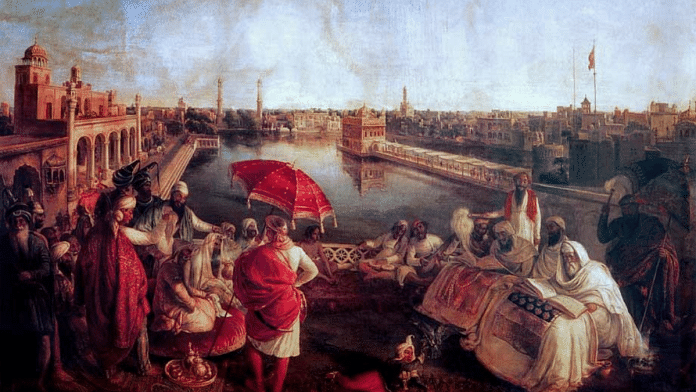

Jat chiefs flocked to Amritsar, where the Khalsa ran a collective at the site of the future Golden Temple. Here, loot from raids was shared among the burgeoning Sikh community, in keeping with village traditions. Soon, these Jat chiefs became the leaders of armed warbands, misals. Despite the rhetoric of dharamyudh, misal leaders raided not only Afghan horse-markets, but Rajput zamindars to their South and the Punjabi-speaking hill kingdoms to their North.

As new groups signed up, writes Dhawan, the Khalsa evolved rapidly. The notion of a hierarchy was still rejected, but individual castes were quietly accepted. The Khalsa also adapted ideas from the Puranas, describing Guru Gobind Singh as a devotee of Durga and avatar of Vishnu. Legends of Gurus were grafted onto local beliefs and ballads. It was a winning strategy. As the 18th century continued to unfold, Mughal presence in Punjab, torn by infighting and external invasion, became more and more erratic. They were focused only on elites, but elites constantly changed sides. The Khalsa was focused on actual farmers and military labour, people who needed the security and honour that the Khalsa offered.

A young man growing up in Punjab could either become a lowly retainer for a Mughal, Afghan, or Rajput lord—or a member of an up-and-coming Sikh brotherhood, with the right to a chiefly turban and various caste privileges and the conviction of a divinely-ordained victory sung to the hymns of Gurus by the campfire. The choice was obvious. Within a single century, the very concept of a military man in Punjab changed from a Persian-spouting, robe-wearing Mughal zamindar to a Punjabi-speaking, turban-wearing Jat Sikh chief. The concept of “us” was no longer limited to individual clans and ethnic groups, which could be mopped up piecemeal by an empire. The diverse new Sikh misal warbands raided and battled each other, but instantly united against “outsiders”.

That’s how, with a little flexibility, community spirit, and eyeing popular sentiment, the Jat chiefs of 18th-century Punjab threw out the Mughal state. Religion was certainly part of it, but we should never ignore the power of an enthusiastic, aspirational peasantry in India’s history.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

Despite having so many reference books on Sikh history, Mr Kanisetti uses an obscure British official’s work to make such foolhardy generalizations.

There is so much incorrect information in this article. For starters, the name of the Guru who was martyred was Guru Arjan Dev and not Arjan Singh- martyred because he was suspected to support a rebellion against Mughals. Also a lot of misinformation about the Sikh Misls and events proposing the timings of presence of “site of future Golden Temple”. FYI, the construction of Golden temple was started by 4th Guru, Guru Ram Das in 1577 and completed in 1604 in the presence of the 5th Guru, Guru Arjan Dev(mentioned above, re incorrect name).

The Sikh Misls, formed in 1700s, defended Golden Temple and not “ran a collective at the site of the future Golden Temple.” They defeated the then Mugals and ruled from the Red Fort for 2 months, during which they broke Aurangzeb’s throne on which he ordered the execution of 9th guru Guru Teg Bahadur and put it in chains in Ramgharia Bunga in Golden Temple. It still exists there.

History is not a joke. This should’ve been properly researched and approved by a historian who is well versed in history of Punjab.