It has been a busy and extractive time in a precise sense in Indian politics. Every week you’re asked to take a position—and that too as a Hindu. The latest list, of course, starts with the question: Are you a Sanatani? Or are you an Arya Samaji? While you are contemplating this, do you think ISKCON is treating cows poorly? Amid all this, don’t forget to have a view on the Uniform Civil Code.

And this is just for starters.

There is also the permanent question of caste and privilege that is at the heart of the raging debate on Sanatan Dharma. Can an individual be identified as a good or bad Hindu? Is Hinduism the same as Hindutva? Now, we are just getting meta, as they say.

Whether you are energised or deflated by this insistent barrage, what’s clear is that the dominant political culture in India continues to make you choose. Hell, no, that’s not enough. One must get riled up, rave, and rant for and against any emerging controversies, which are now two a penny. You will be forgiven if you fear you have an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Meanwhile, Manipur continues to be riven with ethnic clashes and Nuh is still reeling under the shock of the recent communal discord — to say nothing of everyday and extraordinary violence against minorities that appears in chilling social media videos, all too regularly.

Regardless of the state of the Indian economy and India’s status games in turbulent geopolitics, identity talk rules, particularly Hindu identity talk. Nationalist sentiments too seek renewed avowals of identity, whether it is on India’s rising role on the world stage, the successful Chandrayaan-3 mission, or the Cricket World Cup. Prime among the current neo-nationalism moments is the debate on the country’s name itself—India or Bharat—which has now been posed as yet another dilemma.

Political commentators will remind you that the latest focus on (Hindu) identity is a successful attempt to shift focus away from the international headlines on the affairs of billionaire Gautam Adani, which Rahul Gandhi has sought to highlight. Shifting gears to identity, then, is yet another ‘masterstroke’ by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Also read: Modi’s India is coming into its own. Moon landing and G20 Delhi Declaration are…

Hindutva today

For all the grabbing and steering of headlines, this relentless call on identity poses the greatest challenge to the BJP and Hindutva politics itself. First, it is simply too exhausting to merely observe (as I do) let alone affiliate oneself to these loyalty tests. Second, the cacophony is arguably descending into incoherence even as it becomes louder and shriller. Finally, and strikingly so, what’s new?

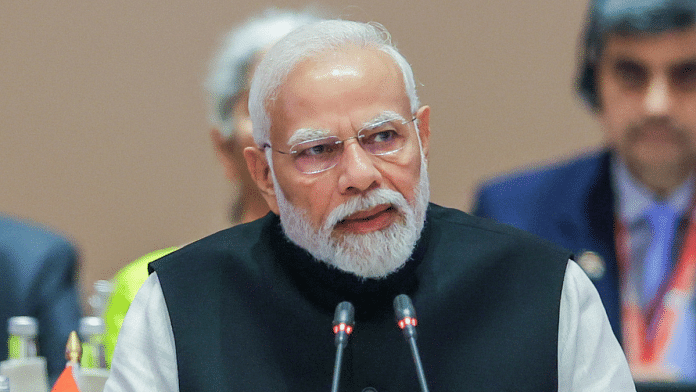

What is new is that despite its recent reinvention under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Hindutva has painted itself into a corner. Arguably, and going by the shrill demands, the next General election won’t be about anything else but how much of a Hindu you are.

The millions of new voters who are going to cast their votes for the first time in 2024 may not recall that in his ascent to the highest and most powerful public office in India, PM Modi had made economic growth and aspiration his mantra. But now, it appears that the PM has returned to peak Hindutva of another era.

During the 1980s, Modi’s predecessors, notably L K Advani, (quite literally) fired up India on the visceral agenda that Hindus were in danger, victims of history who had to reclaim the soil. The Ram Mandir movement, which started in the middle of the greatest mandate for the Congress party mid-decade, did not yield immediate political heft for the BJP but did its job. It made the BJP a national contender.

Tellingly, in 2014, Modi did not centralise the Ram Mandir issue. It was the economy — ‘Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas’ — and emotions ran high on corruption scandals involving the Congress. Money and the economy emerged as the fixating theme and led to Modi’s emergence as the everyman of India taking charge of the nation. By muting the high decibels on Ram Mandir, Modi crafted an unprecedented victory for a non-Congress party in Indian democracy.

In his second victory in 2019, the security State apparatus and attendant nationalism, which followed the Pulwama attack, Modi epitomised the strongman of the new century. Even though the BJP had incurred losses in key states such as Rajasthan in the winter of 2018-19, a strong Modi-led India with Kashmir as the centrepiece emerged. He won back and big.

Today, though, we seem to be back in the last century of the ‘Hindu khathre mein hai (Hindu is in danger)’ slogan but with a crucial twist. The Hindu nationalist party today is deeply entrenched in Indian politics, as it has been in power for nearly a decade.

Also read: Corruption, infighting, indiscipline—why BJP, not Congress, is bigger headache for Modi now

Vishwaguru or victim

Modi’s second term is not saddled as much by anti-incumbency as it is with an identity crisis. Having successfully reinvented Hindutva in his own personality, it is not clear whether we are looking at a strongman Vishwaguru or the representative of a so-called victimised identity. The relentless loyalty tests attest as much.

On the world stage, India has been able to prevail through its Covid vaccine diplomacy, a successful lunar landing, and the marquee event of G20. India, under Modi, seems at the centre of the top global table. Brooking little to no critical appraisal of emerging geopolitics, the Indian political sentiment is such that whether it is Canada or Russia, to say nothing of China, Delhi, under Modi, has bestowed power, leverage, and recognition to its global ambitions. Delhi can indeed buy arms from Moscow and hold military exercises with America in the Indo-Pacific at the same time. This lends to Modi’s image as the Vishwaguru or guide to the turbulent weather that has overwhelmed the world order.

Yet, domestically, it is the victim that remains the true calling card. Modi’s own humble backstory, which inspired millions a decade ago, now looks distant. Is he a strongman prevailing over hostile foreign powers or the chaiwallah who ascended to the top office? Empirically, he is both. But in an immediate sense, Modi is more the aloof strongman than the everyman.

In an analogous way, Modi’s second term has been an answer to Hindu identity politics. From the policy on Kashmir that opened the new mandate’s rule in 2019 to the inauguration of the Ram Mandir slated for January 2024, Modi’s second term has appealed primarily and openly to Hindu identity.

Today, the biggest question in Indian politics isn’t what Sanatan Dharma is or whether there’s something called a good or bad Hindu. The question is: Is PM Modi the great protector or one who needs your protection? Is he Vishwaguru or the victim? He should know, and he can’t be both.

The BJP is the party of identity in India. Yet, it is the BJP today that faces an identity crisis.

Shruti Kapila is Professor of History and Politics at the University of Cambridge. She tweets @shrutikapila. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)