Mahatma Gandhi’s inconsistent stand on caste has been criticised by some leaders.

Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary year presents before us a legacy, which has been widely respected as well as criticised by certain quarters.

While Gandhi is hailed as a powerful inspiration across the globe, he has sometimes been called “casteist” in his own country. His contemporary B.R. Ambedkar questioned his views on the caste system, and forced him to rethink. Historian Rajmohan Gandhi has called caste “the most discussed Gandhi-related” issue in present India.

From critical to radical

Gandhi’s stand on caste changed over the years. Although eradication of untouchability was one of his passions, he remained an advocate of the caste system for long. For instance, in 1921, he wrote in his journal Navajivan, “[I]f Hindu Society has been able to stand, it is because it is founded on the caste system”. While being an admirer of the caste system, he believed that there should be no hierarchy between castes and that all castes should be considered equal.

Also read: You don’t know Gandhi if you don’t know about his 3 Gujarati comrades

By 1930s, however, he had become critical of the caste system. On 16 November 1935, he wrote in an article, “The sooner public opinion abolishes [the caste system], the better”. The article was published with this title in capitals – ‘CASTE HAS TO GO’.

As Independence neared, Gandhi became radical in his ideas. When he went to Noakhali in eastern Bengal (in January 1947) to tackle the communal violence there, he gave, as Rajmohan Gandhi calls it, a “radical advice” to the upper-caste Hindu women. “Invite a Harijan every day to dine with you. Or, at least ask the Harijan to touch the food or the water before you consume it. Do penance for your sins”.

In April 1947, he announced that he will give his blessings only to weddings between Dalit and non-Dalit. Gandhi was the first one to propose (in June 1947) the idea of appointing a Dalit man or woman as the first president of Independent India. He believed that this would be a ‘strong symbolic move’ towards eradication of caste differences. Although his proposal was not accepted, Gandhi’s bold new avatar tackled the notions of caste privileges and prejudices.

In fact, Gandhi’s inconsistent stand on caste has been highlighted and criticised by one of his closest disciples, Ram Manohar Lohia. Lohia felt that “Gandhi was not aware of the full implications of the caste system right up to a few years before his death”. While observing that “[it] is true that [Gandhi] had all along tried to remove untouchability”, Lohia termed Gandhi’s initial view on caste system as that of a “reformer’s act, and not a revolutionary’s”.

Also read: The two family members of Mahatma Gandhi who dared to disagree with him

The clash and the change

Intellectual curiosity is a good reason to contemplate what caused change in Gandhi’s perception on caste. Gandhi of 1915 was different from Gandhi of mid-1930s. In his latest book Gandhi 1914-1948: The Years That Changed the World, Ramachandra Guha has contemplated that the transformation in Gandhi’s perception of caste and “his increasing willingness to challenge its prejudices” were a direct result of his engagements with social reformers who were “more radical than himself”.

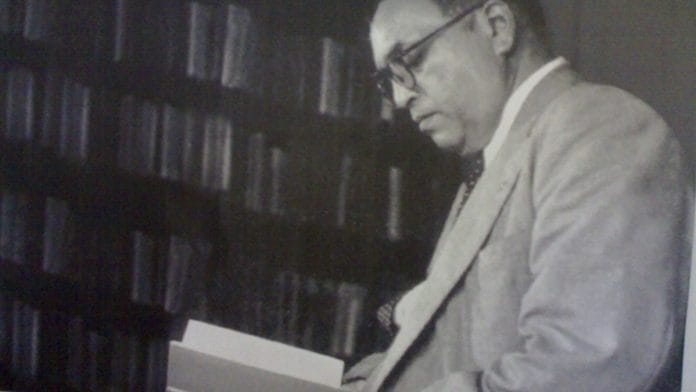

Ambedkar was a powerful radical figure contemporary to Gandhi, who questioned his views. Ambedkar, an admirer of Gandhi for some years in the 1920s, became openly critical of Gandhi’s ideas since August 1931, when the two met for the first time.

Ambedkar and Gandhi then clashed at the 1931 London Roundtable Conference over separate versus joint electorates. When separate electorates were announced and Gandhi began his fast in Yerwada jail to oppose it, Ambedkar met Gandhi again to defend the cause of “political power” for his community. While Ambedkar bargained hard for his community, both settled for a compromise – famously called the “Poona Pact”, which allowed quotas or reservation for Dalits in legislature.

After the Poona Pact, Ambedkar went to see Gandhi again in Yerwada to discuss the best way to end untouchability. While Gandhi’s focus was on temple-entry for Dalits, Ambedkar told Gandhi that “the crying need is the raising of the economic status and decent behaviour in the daily contact [between Dalits and non-Dalits]”. Gandhi issued a statement that he “felt the force of [Ambedkar’s] remarks” and hoped that others will do likewise.

Also read: Mahatma Gandhi’s little-known love affair with a married, progressive woman in Lahore

In later years, Ambedkar did not leave any occasion to pick holes in Gandhi’s theoretical defence of the varna system. He advocated complete destruction of the caste system. It can be said that as Ambedkar boldly challenged Gandhi’s views on the caste system, he forced him to rethink his ideas. “From his belief that the caste system was a part of religion”, Lohia once said, “[Gandhi] went on to say that it was a sin”.

In his last years, Gandhi expressed his eagerness to have Ambedkar join the first cabinet. Ambedkar agreed and piloted the Indian Constitution into force, which provides civil rights to Dalits and abolishes untouchability.

Anurag Bhaskar is an LLM student at Harvard Law School. He tweets @anuragbhaskar_