From his table inside the lavish, red-enamel interiors of 181 Avenue Foch—surrounded by games of mahjong, pai gow, and cards, and waiters scurrying about with complimentary opium and wine—detective-squad chief Huang “Bigshot” Jinrong looked out at one of the greatest criminal empires the world had ever known. The Big Eight Mob controlled the opium business, gambling, prostitution, the fish market, at least two major banks and the police itself. Three of every hundred Shanghai residents made their living from crime.

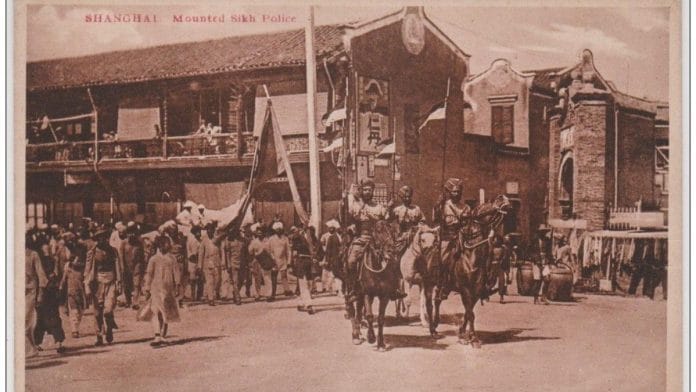

To keep the flotsam of drunks, small-time thieves and sex workers from spilling into the city’s upmarket casinos, the Shanghai Municipal Police (SMP) had hired a small army of men from another world: Men with long beards and bright-red turbans, brought in from small villages in Punjab’s Majha region.

For the most part, the 558 men who served in what was known as the SMP Sikh branch disappeared from history when it was disbanded eighty years ago, in 1943. From the surviving records, though, we know constable Isser Singh was out on the violent streets of Hongkou night after night. The historian Isabella Jackson tells us Isser arrested a drunk American sailor on 19 December 1906 and locked up an unruly Russian who obstructed traffic on Boone Road the next summer.

The Sikh constabulary was also key to putting down riots and political disturbances—leaving behind a legacy of resentment that still colours popular culture in China.

Also Read: Why does the ghost of Khalistan still haunt Punjab? Story of this father & son has answers

Control of sin city

Few great cities have had a social fabric as closely entwined with organised crime as Shanghai. Through wars fought in the nineteenth century, scholar Julia Lovell writes, the colonial powers prised open China to opium grown in India. In 1839, China confiscated some 1,000 tons of opium from British dealers in Guangzhou. London responded by demanding that the Chinese emperor compensate the traders for the street value of their drugs. The emperor refused, leading Britain to unleash its warships against China and bombard its coastal towns. Shanghai was divided into foreign-controlled enclaves.

Like all criminalised polities, though, Shanghai proved hard to control. Chinese police supplemented their income by running their own gambling houses, brothels, opium dens. Taking bribes was commonplace. To make things worse, local constables were unable—or unwilling—to aggressively coerce the local population.

Even as authorities struggled, criminal cartels enforced their authority ruthlessly. The Green Gang, one the constituents of the Big Eight, was infamous for dealing with bothersome rivals by severing every visible artery of their victims with a fruit knife and leaving them to bleed to death, records scholar Peng Wang. The Big Eight even institutionalised a code of punishment with sentences ranging from three stabs in the lower leg to nine cuts to the thigh.

The reticence of local police to act was familiar to imperial authorities. The early London police commissioners Richard Mayne and Charles Rowan, criminologist Clive Emsley noted, came to rely on rural recruits, realising that local police were too enmeshed with the community to play a coercive function.

From late in the nineteenth century, Jackson records, Indians began to be deployed in police roles across the empire, from Uganda and Mauritius to Fiji and Malaya. Hong Kong’s Sikh police “acquired a reputation amongst the British officers for their loyalty and martial prowess in service to the Empire.” The example led Shanghai to also seek out Sikh recruits from Majha, for whom it set up a training school in 1896.

Also Read: The cost of being an Indian spy. What happened to Ravindra Kaushik, R&AW’s Black Tiger

Fairbairn’s army in Shanghai

Lieutenant Colonel William Ewart Fairbairn—a Royal Navy marine who had learned martial arts while stationed in Korea, and is famous for designing a knife still used by commandos—turned the SMP into a formidable force. His innovations, expert Leroy Thompson has recorded, included the Red Maria, a scarlet-coloured armoured car equipped with machine guns, tear-gas canisters, grenade launchers and electric searchlights. The car, which carried up to fifty especially-trained personnel, allowed the police to confront Shanghai’s increasingly well-equipped criminals.

The Red Maria was involved, among other things, in a nineteen-hour gunfight against armed kidnappers in 1928, which saw over 700 rounds fired.

Fairbairn—who went on to found a martial arts technique he called “gutter fighting”—also developed the SMP Sikhs into a disciplined riot-control force, with many receiving Kung-fu inspired training. Two lines of 12 lathi-carrying Sikhs would follow Chinese police using European-style short batons, to break up labour disputes and riots. The Sikhs played a key role in an anti-gambling crackdown in 1929, sometimes targeting illegal establishments operated by ethnic-Chinese police. The essence of Fairbairn’s teachings is evident from the blurb of his book: “With your bare hands, you can beat the man who wants to kill you.”

In one internal report, the SMC noted that the Chinese rickshaw pullers feared the Sikhs: “Years of experience have proved that these men obey police signals not so much from any respect for the law as from the fear of consequences to themselves if they do not. The traffic baton serves as an outward emblem of the physical force behind the law.”

The role of the Sikh police in combating civil disorder embittered the population and became a symbol of colonial authority. The writer Cao Juren, arriving in Shanghai in the first decades of the last century, noted the presence of “Sikh policemen on streets, whose faces were black and who wore red turbans.” Stories of sexual violence by Sikhs against local women proliferated in pop fiction.

“I know them,” one Shanghai resident told scholar Cao Yin of the Sikhs. “They were slaves of the British. Indians were not good to us.” As a result of those colonial-era encounters Yin observes, “many Chinese nowadays hold certain distorted and imaginary grudges against Indians.” Less known to the Chinese, the Sikh constabulary also played a key role in colonial surveillance of suspected Indian nationalists in Shanghai, infiltrating the local Gurdwara in search of dissidents.

The fragmentary evidence we have of Isser Singh’s story suggests it did not have a happy ending. In April 1911, he was arrested on charges of drunk and disorderly behaviour, after assaulting a Chinese man on Sichuan Road. The policeman himself was sentenced to a fine of $10, and seven days of hard labour. It is unclear if he was reinstated to the police force.

Following the fall of Shanghai to Japanese forces in 1937, the SMP fell apart. Some of the 500-odd Sikh personnel on its rolls served as prison guards for Japanese forces, with at least two receiving war-crime sentences after the end of the Second World War. Some personnel also seem to have ended up in the Indian National Army, while most returned to India. The last remaining Sikhs of the SMP were repatriated home in 1945.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.