From his inglorious throne on the open toilet a few dozen metres from a Border Security Force outpost—protected by three armed guards in case an enemy patrol strayed across the wheat fields—the Tamil-speaking intelligence officer considered his mission. Later that night, as the moon rose, he’d shake hands with the agent he’d trained to live undercover in Pakistan and wish him well. Then, once the man disappeared into the shadows, head back to Amritsar, hoping the R&AW station’s famously-asthmatic jeep didn’t break down.

The most epic stories of espionage in South Asia are cloaked in dust, diesel fumes and flies. They’re also stories of brave individuals who were left to die in the heat of Pakistani prisons, unrecognised by successive governments.

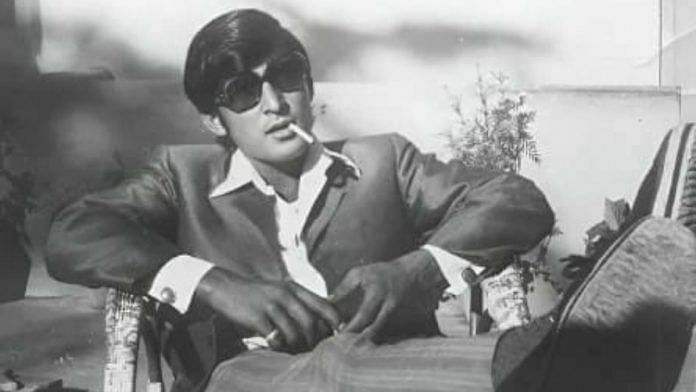

Today, Ravindra Kaushik—the fabled Black Tiger of R&AW, who died in Pakistan’s Mianwali prison, and the man sent across the border that night in November 1975—would have turned 71. Kaushik’s story has inspired books and even a movie.

There has been little dispassionate accounting, though, of what the spies of Project X—the super-secret R&AW effort to plant long-term resident agents at the heart of Pakistan’s establishment—actually achieved, and at what cost.

Project X was shut down by R&AW 20 years ago after its assets and their military-intelligence missions were rendered redundant by sensors on aircraft and satellites. There’s no memorial to the agents who gave their lives.

Also Read: Jaipur bombing acquittal shows chinks in India’s criminal justice system. It has consequences

The making of a spy

Even as he worked his way through an accounting degree at the Seth GL Bihani SD Post Graduate College in Rajasthan’s Sri Ganganagar, Kaushik appears to have developed an interest in theatre. The son of a civilian who served in the Indian Air Force, Kaushik is also reputed to have soaked in stories of war. Sri Ganganagar was among the hubs for the grey world of traffickers who also served as part-time spies for the Intelligence Bureau and Military Intelligence; Kaushik almost certainly would have heard their stories.

Files on the case have not been declassified, but the R&AW officer familiar with his case said the 1952-born student came into contact with officials at the agency’s Sri Ganganagar station and volunteered for service.

Two years of rigorous training followed after he was recruited in 1973. Among other things, officers who taught Project X recruits told ThePrint, Kaushik was schooled in Urdu, Islamic religious practices and underwent a circumcision. He was taught how to sustain a fiction—the term intelligence officials use for a cover identity—and to defeat surveillance.

From 1975 on, historian Hamish Telford reminds us, politics in Punjab became ever-more volatile, with Akali political groups rising against the Emergency, and the revanchist cleric Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale acquiring increasing power.

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, who took power in a 1977 coup, hoped to leverage the chaos to his advantage—and India feared he could go to war.

Project X, designed to detect early signs of Pakistani military mobilisation, became a key weapon in India’s intelligence arsenal.

Also Read:No one knows R&AW agents better than Pakistanis—from Pathaan to Mission Majnu

An incandescent script

Early in 1975, R&AW officials say, Kaushik had been equipped with a fiction, complete with a birth certificate and tenth-grade matriculation certificate, identifying him as Islamabad resident Nabi Ahmad Shakir. The agent, the officials said, thought he ought to apply for the Pakistan Army’s officer-recruitment examinations. The idea was shot down by R&AW officers on the grounds that his documentation and fiction would not survive verification. The college graduate thus applied for and secured a clerical job in the Pakistani Army.

The material that flowed from this office was a goldmine for the agency. From his position in Pakistan’s military accounts service, Kaushik was able to report on the movements of military units, the postings of key officers and even the movements of trains with war material.

Like other agents in Pakistan, one senior R&AW officer recalls, Kaushik relied on the postal system to send back intelligence—recording his information long-hand in invisible ink and then mailing the notes to addresses in Kuwait or Dubai. “Those were more languid times,” the officer says, “and it wasn’t unusual for information to land a month or six weeks after Kaushik had sent it.”

Files on Kaushik reviewed by R&AW in the mid-1990s—still taught at its training academy—do not provide conclusive evidence for just how Pakistani counter-intelligence detected him. A part of the story, an officer familiar with the review said, was the arrest of R&AW agent Inayat Masih in 1983, who was sent in as part of a mission to bring Kaushik home for a short break.

Kaushik had married Amanat Nabi, the daughter of a soldier in his department, and had a child. The absence of relatives in the spy’s life might have, some R&AW officials claim, led Pakistani counter-intelligence to begin surveillance on the agent. Kaushik was sentenced to death in 1985, which was later commuted to life in prison. The agent died in Mianwali prison of illness in 2001.

Even though Kaushik’s family relentlessly lobbied Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to secure his return, journalist Dalip Singh reported, New Delhi refused to acknowledge he was a spy. “We don’t want money,” his brother RN Kaushik said, “What we want from the government is recognition.”

Also Read: Mehul Choksi tale shows how legal systems make old pirate citadels a shelter for rich criminals

Tales of betrayal

There is no telling how Kaushik’s life might have played out if his family succeeded. Karamat Rahi, who conducted multiple transborder missions for Indian intelligence services from 1983 to 1988, spying on movements in cantonments, ended up selling tea outside Gurdaspur after his eighteen-year prison sentence. The spy fought a long and unsuccessful battle for compensation before his death in 2016.

Former military intelligence agent Surjeet Singh, who says he carried out dozens of cross-border espionage missions, spent thirty years in prison after being arrested in 1981. Journalist Geeta Pandey reported his family received a Rs 150-per-month pension during this period.

The R&AW agent Roop Lal Sahariya, who spent 26 years in jail in Pakistan before finally being sent home in 2001, was promised a petrol pump on his return—but had to petition the courts to get it. Paralysed by beatings received during interrogation, Sahariya also ended up losing his family in India, after his wife remarried.

Later reduced to selling wooden handicrafts on a Kolkata street, former Pakistan Army soldier Mehboob Elahi Shamsi was recruited by the Intelligence Bureau while visiting relatives in India. In August 1980, he was sentenced to a life term in Pakistan, and then quietly pushed across the border near Barmer in a 1996 prisoner swap. This time, he was held in an Indian jail, until his story was finally corroborated.

Among the Indian spies Shamsi spent time with in Kot Lakhpat Jail was Sarabjeet Singh—slain in a jail-house riot in 2013. Sarabjeet Singh is thought, though never proven, to have participated in bombings inside Pakistan, carried out to retaliate against Khalistan terrorism. “The role of our covert action capability in putting an end to the ISI’s interference in Punjab,” former R&AW officer B Raman wrote in 2002, “by making such interference prohibitively costly is little known”.

“Even if you escape death,” the former Indian Military Intelligence agent Kishori Lal Sharma bitterly recalled, “you die a slow death as nobody is there to own you.” Lal, who operated undercover as a small businessman in Lahore, led a group of former agents seeking pensions similar to those granted to soldiers. The effort, however, went nowhere.

For Indians schooled by reel life, the spy ends his story in Venice, Cape Town, Zurich, and London, and the sentence is served together with Katrina Kaif. The real-life ending is grimmer.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)