To believe the BJP will lose the support of Lingayats en masse because of a single decision is a reductionist understanding of how parties and caste groups are aligned in India.

There is a lot of clamour over Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah’s decision to recommend religious minority status for the Lingayats. A prosperous agrarian community in the state, the Lingayats are approximately 17 percent of the state’s population and form the core support base of the BJP. Many believe that Siddaramaiah’s move has sealed the BJP’s fate in next month’s assembly elections.

The promise of a religious minority status may certainly boost Congress’ prospect among Lingayats, but to believe the BJP will lose support within this community en masse because of a single decision is a reductionist understanding of how parties and caste groups are aligned in India.

Political parties around the world are rooted in social cleavages, which helps in them enduring for a long period of time. The social base of political parties do undergo transformation, but it does not happen overnight. Even big momentous shifts, such as the rise of the BJP in Tripura in 2018 happened at the expense of the Congress (and not CPM), which has been losing support in the state for more than two decades now.

The Lingayats in the pre-1990s were largely aligned with the Congress party, but the community began moving away from the Congress after the then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi abruptly sacked Veerendra Patil, a Lingayat, as CM. It took the BJP almost two decades to become the preferred party of the community in the state.

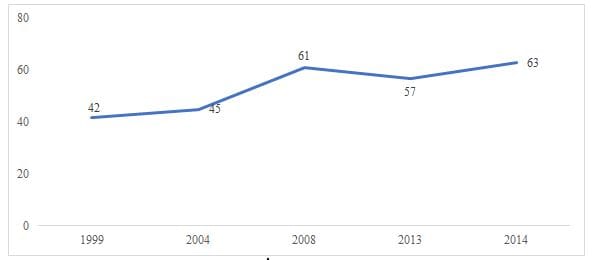

The time-series data collected by Lokniti-CSDS suggests that in late-1990s, four out of ten Lingayats voted for the BJP. This support base was carefully cultivated, and now more than six out of ten Lingayats vote for the BJP. It is important to note that even when former chief minister Yeddyurappa, a popular Lingayat leader, broke away in 2012 and contested as a separate party (the Karnataka Janata Paksha or KJP), the BJP still managed to hold on to half of its Lingayat vote base. Yeddyurappa is now back in the BJP and has been projected as the CM face, so it is unlikely that Siddaramaiah will dent the BJP’s traditional base in a big way.

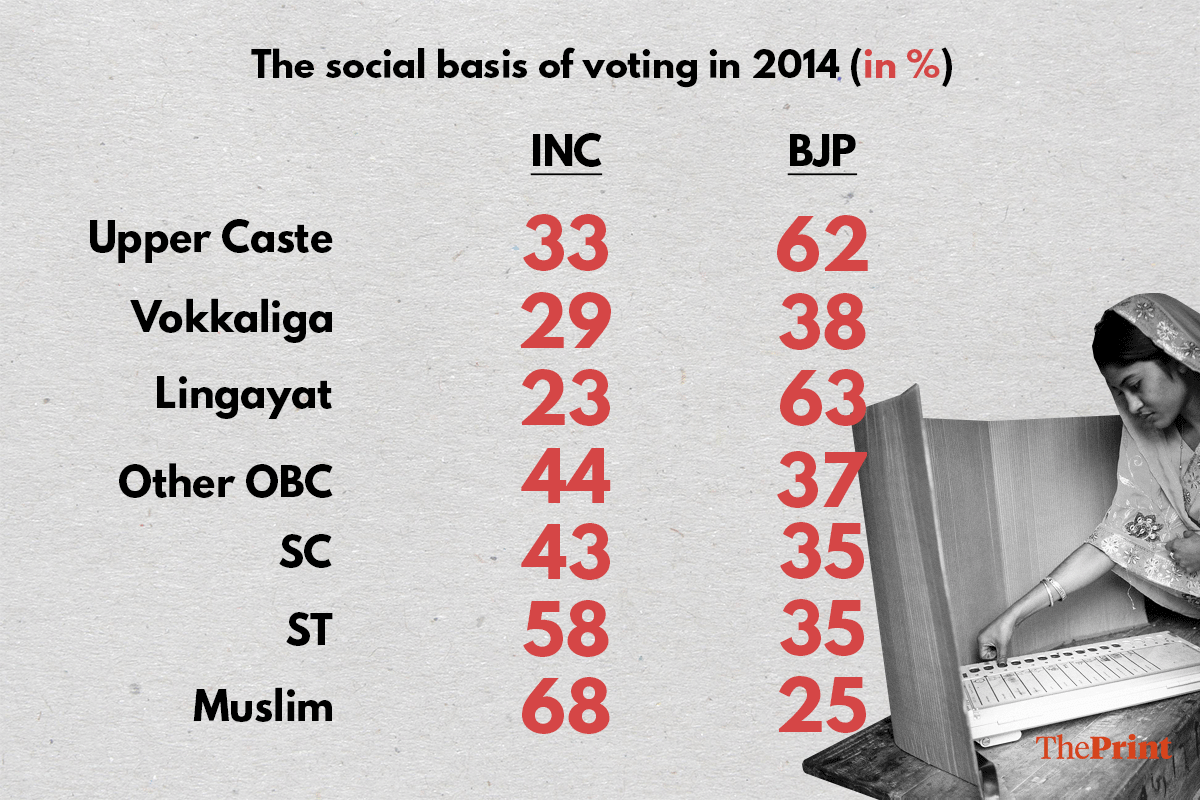

Siddaramaiah is perhaps aware of this. So why did he choose to recommend religious minority status for the Lingayats? This, in our view, is classic hardball politics. The BJP, since 2014, is making all efforts to make inroads within the Congress’ social base. The data presented in Table 1 shows that the BJP’s vote share among Vokkaligas and Dalits almost doubled since 2013. This move by Siddaramaiah is in a way of signal to the BJP leadership: Stay away from my pie, else I’ll upset your apple cart.

To neutralize the effect of Siddaramaiah’s move, the BJP now has to work extra hard. This has become evident in BJP president Amit Shah’s speeches during recent visits to the state. He attacked Siddaramaiah saying that the decision to accord religious minority status is not only to break Lingayat-Veerashaiva unity, but also an attempt to prevent Yedyurappa, the foremost Lingayat politician in the state currently, from becoming the chief minister.

Since 2014, the BJP has inducted several high profile Vokkaliga leaders, including former chief minister SM Krishna. In the eight southern districts of Karnataka, popularly known as Old Mysore region, there are districts like Mandya, Hassan, Ramanagara and Chamarajanagar districts, where the Vokkaliga population is very high. The BJP wants to break into the JD(S) and Congress stronghold by splitting the Vokkaliga vote.

The BJP has done relatively well among Vokkaliga voters in 2009 and 2014 Lok Sabha elections. The key question is whether the BJP would manage to hold on to its newly won support base among this group.

Furthermore, the Congress in the state relies heavily on the stability of its AHINDA coalition (a Kannada acronym for religious minorities, backward castes, and Dalits). In 2014, the Dalit vote in the state was almost equally split between both parties: 43 per cent voted for the Congress, and 35 per cent for the BJP. Two developments in the past few months may hurt the Congress’s chances among this group. First, the BJP is trying to create an internal fault line within Dalits by targeting the Madiga voters. And second, the BSP’s pre-election alliance with the JD(S) could further split the Dalit votes in the state.

To conclude, though the popular discourse on the 2018 Karnataka elections is centred around the Lingayats, the outcome is likely to be decided by what happens to Vokkaliga and Dalit vote in this election.

In our view, both parties are locked in terms of their social bases, and thus in effort to win new voters, they are encroaching upon the support base of others. At the moment available evidence suggests that the parties are neck and neck, and at this stage, this election could swing either way.

The writers are PhD students in political science at University of California Berkeley, US.