73 years ago, on 27 July 1949, a historic agreement was signed between India and Pakistan. Though forgotten by many, it is perhaps the most important agreement between the two nations and one which not only laid the groundwork for all subsequent agreements (Tashkent & Simla) but also established what is the de-facto border between the two nations today. Popularly known as the Karachi Ceasefire Agreement, it is formally referred to as the Agreement Between Military Representatives of India and Pakistan Regarding the Establishment of a Cease-Fire Line in the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

Pursuant to India’s complaint to the UN on 1 January 1948 about Pakistani assistance and involvement with the invaders in Kashmir, the Security Council sent out a UN Commission to the sub-continent (UNCIP or the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan). This Commission produced two Resolutions (13 August 1948 and January 1949) which aimed at bringing about a truce between the two warring nations by drawing a ceasefire line and effectuating a comprehensive solution to the Kashmir dispute by carrying out a plebiscite. Part I of the 13 August Resolution dealt with the ceasefire order and Part II with the truce agreement. Both India and Pakistan had no dispute on Part I of the Resolution and agreed to abide by and implement it.

When the lines were drawn

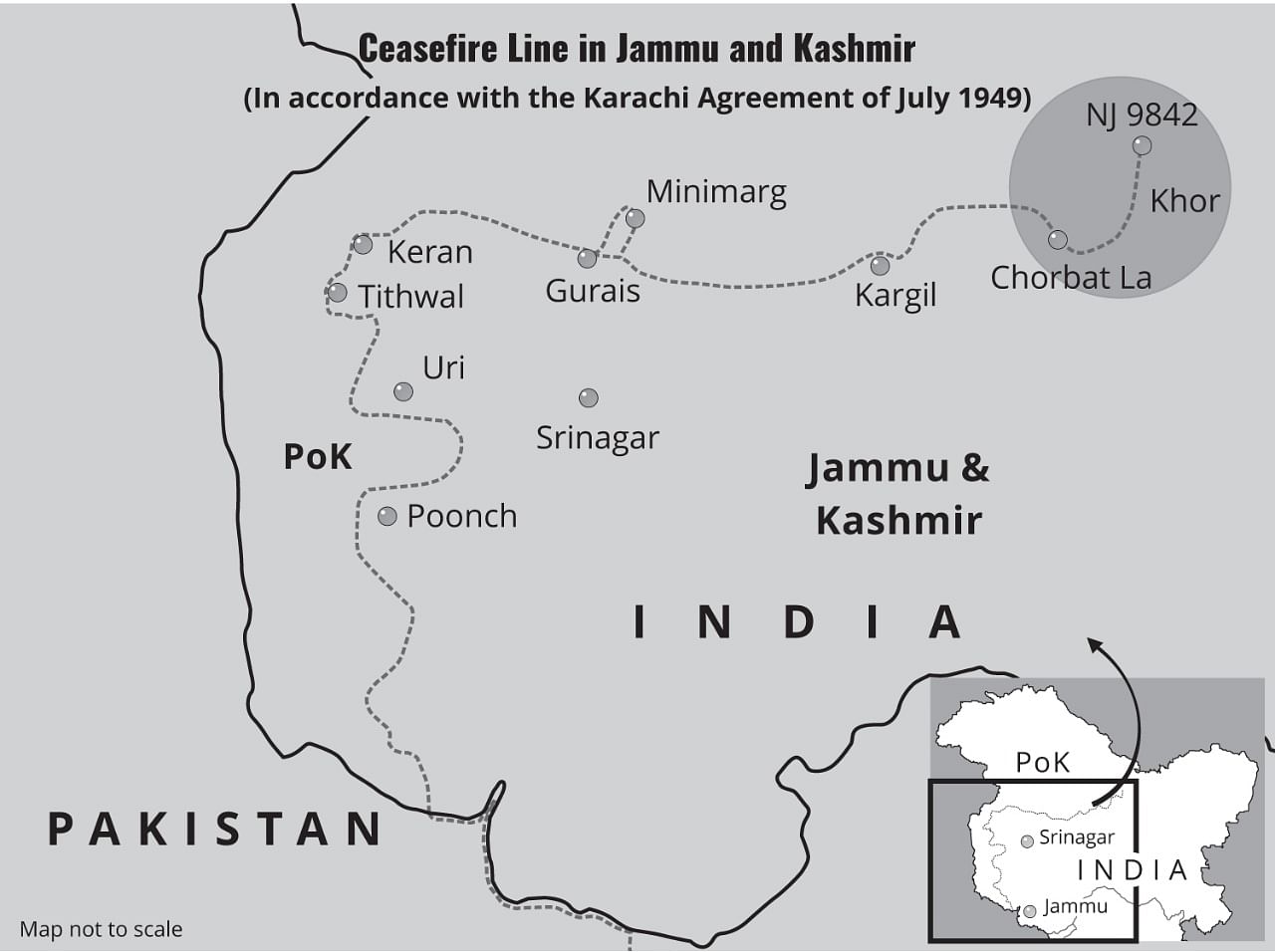

After very elaborate and exhaustive discussions between the Indian and Pakistani representatives, a ceasefire line acceptable to both parties emerged and the agreement, under the auspices of the UNCIP, was finally signed on 27 July 1949. Such was the persuasive force and sanctity of this internationally brokered agreement that even in 1965, after the Tashkent Agreement, both sides agreed to return each other’s gains and losses and revert to the post-Karachi positions.

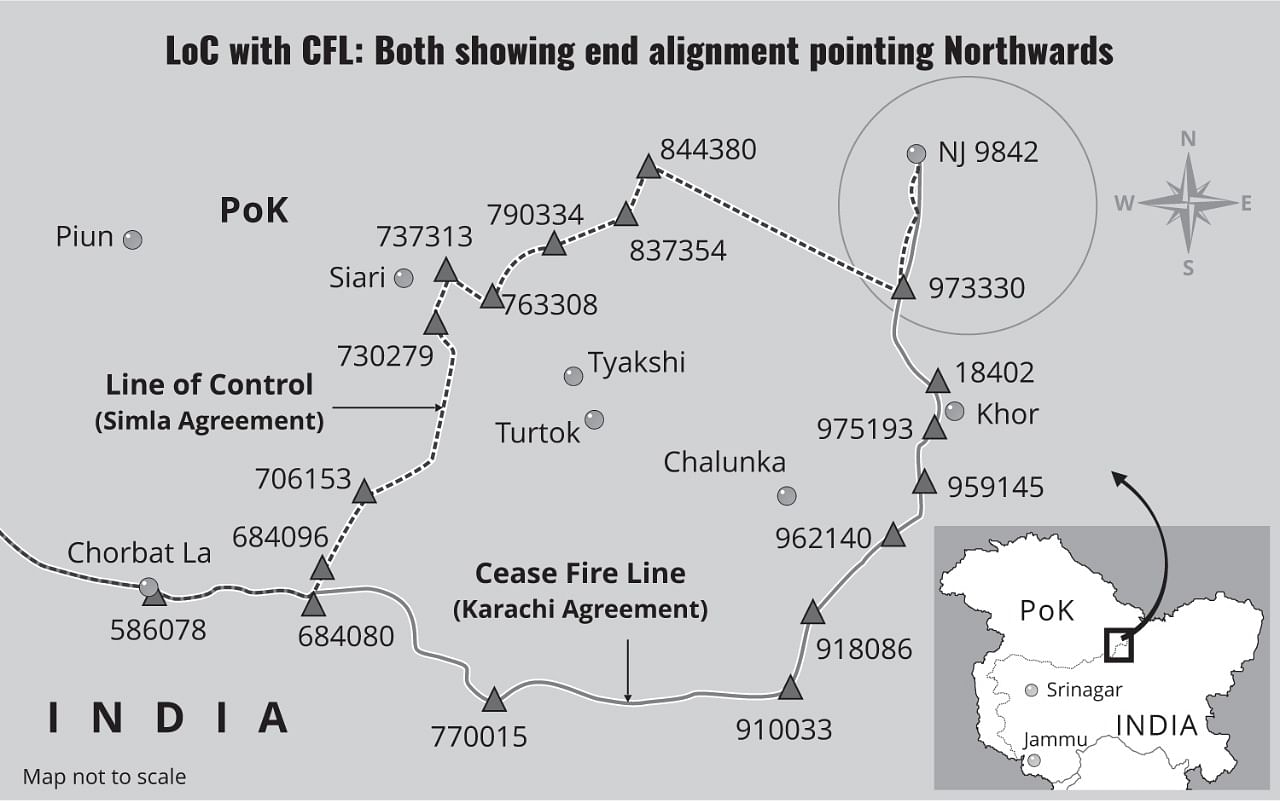

However, after the 1971 war and after the bilateral Simla and Suchetgarh Agreements, the gains of war were retained by the parties. Therefore, the Karachi ceasefire line was realigned to incorporate them. The new line that emerged indicated the areas controlled by the respective parties, and so it was called the Line of Control or the LoC. Thus, our de-facto border with Pakistan is nothing but the original Karachi ceasefire line tweaked to adjust the gains of 1971. Today, many argue that post-Simla, the Karachi Agreement has lost its relevance. On the contrary, this Agreement is very much valid even today and deals with an area Simla does not talk about. In fact, it holds the key to solving the Siachen dispute.

In 1949, the main objective of the UNCIP was to temporarily separate the two warring armies and restore peace till the final fate of the region was decided. The Truce Sub Committee was not a boundary delimitation commission and did not involve any surveyors or cartographers but consisted of experienced military men on both sides who were trying to calm the volatile situation. And yet, the Karachi Agreement delimits and describes in great detail the entire stretch of the more than 500 mile long ceasefire line from Manawar till the glaciers in the North. Thus, the delimitation of the ceasefire line as per the Karachi Agreement is clear and complete.

The relevant clauses of this Agreement, which deal with the Siachen region, are reproduced below:

B 2 (d) From Dalunang eastwards the ceasefire line will follow the general line Point 15495, Ishman, Manus, Gangam, Gunderman, Point 13620, Junkar (Point 17628), Marmak, Natsara, Shangruth (Point 17531), Chorbat La (Point 15700), Chalunka (on the Shyok River), Khor, thence north to the glaciers. This portion of the ceasefire line shall be demarcated in detail on the basis of the factual position as of 27th July 1949 by the local Commanders, assisted by the United Nations Military Observers.

C. The ceasefire line described above shall be drawn on a one-inch map (where available) and then be verified mutually on the ground by local commanders on each side with the assistance of the United Nations Military Observers, so as to eliminate any no-man’s land. In the event that the local commanders are unable to reach an agreement, the matter shall be referred to the Commission’s Military Adviser, whose decision shall be final. After this verification, the Military Advisor will issue to each High Command a map on which will be marked the definitive ceasefire line.

Unfortunately due to the hostile terrain the physical demarcation and abornement of the ceasefire line was not completed till the glaciers but was stopped at a point short of the same bearing grid reference NJ 9842. This was obviously done by the mutual agreement of the parties as no reference pertaining to this region was made to the Military Adviser as envisaged in Clause C. As a consequence the delineation of the line on the maps (which was to be done subsequent to the signing of the Agreement) too was incomplete. Similar was the position in 1972. Since there were no hostilities in this region and no dispute/claims/counterclaims regarding it by any party the LoC too ended at the same grid point i.e NJ 9842 and no further demarcation of the region beyond it was undertaken. Pakistan considered the region beyond NJ 9842 as a no man’s land and started asserting its claim to the same by sponsoring expeditions and relying on international maps which in turn prompted India to launch a military expedition in 1984 to pre-empt Pakistan’s occupation of the same. Even 38 years after the military operation there continues to be a divergence of views on the interpretation of the aforementioned Clauses of the Karachi Agreement.

Also read: Kumar’s line vs Hodgson’s line: The ‘Lakshman rekha’ that started an India-Pakistan fight

It’s time to revisit the Agreement

A.G. Noorani, in his article Fire on the Mountain (The Illustrated Weekly of India, 30 June 1985), described the Siachen region as a no man’s land and said that the Karachi Agreement left the northern extremity of the ceasefire line vague. This vagueness of Karachi theory was reiterated by Robert Wirsing in his article and several others thereafter, to argue that because of the inherent ambiguity in the Agreement, it was capable of multiple interpretations, including the one given by Pakistan. The phrase ‘thence north to the glaciers’ was pronounced guilty and held responsible for the dispute, without anyone actually reproducing the relevant clauses and explaining what was not clear therein.

It has since been argued that as per Karachi, the ceasefire line ends at NJ 9842 and is not supposed to go North thereafter and therefore the area beyond NJ 9842 is a ‘no man’s land’. However, a plain reading of the aforementioned clauses shows that they envisage demarcation to be done subsequent to the execution of the Agreement. The alignment of the ceasefire line is clearly described in simple language capable of one interpretation alone, in the same manner as has been done in various other clauses of the Agreement leaving no room for any confusion. The words North, South, East and West have also been used repeatedly in various other clauses and have been clearly understood and implemented without any ambiguity.

The use of the phrase ‘shall be’ in Clause C shows that on the date of signing of the Agreement, only the delimitation was agreed to and the rest of the things had to follow in consonance thereof. Thus, NJ 9842 is the northernmost and last demarcated point on the ground en route to the glaciers and not the terminal point as per the Agreement. Clause B2d clearly mentions that the line has to proceed to the glaciers, therefore the question of it terminating before the glaciers does not arise. If that were to happen, then the entire tract of land thereafter would become a ‘no man’s land’, which is contrary to the mandate of Clause C of the Agreement.

Incomplete demarcation of the region subsequent to the Agreement cannot be construed to imply an absence of agreement concerning the region. The argument that the line is not required to go North beyond NJ 9842 is also without merit as the Agreement clearly mentions ‘thence north to the glaciers’ and not ‘thence north to NJ 9842’. In fact, the grid reference NJ 9842 is not mentioned anywhere in the body of the main Agreement but emerges only during the subsequent process of demarcation, clearly showing that though the Agreement envisaged the ceasefire line to go North till the glaciers, yet it stopped abruptly at NJ 9842 before the glaciers due to extraneous considerations.

Many scholars say that the Simla Agreement overrules the Karachi Agreement insofar as Siachen is concerned because it refers to the LoC going eastwards to the glaciers. This is also far from the truth. A reference made by then-external affairs minister Swaran Singh in a parliamentary statement describing the orientation of the LoC is often mistakenly quoted as being the text of the Simla Agreement when, factually, the LoC as per Simla terminates at NJ 9842.

The words ‘thence north to the glaciers’ are exclusive to the Karachi Agreement, which remains the only legal document dealing with the region beyond NJ 9842.

Siachen is one area where despite several historical disagreements on Kashmir, both India and Pakistan had, in fact, agreed to agree, in writing and that agreement stood the test of time with both the 1965 and 1971 wars not seeing any action in this theatre. Despite express delimitation in its favour, India always maintained the Karachi status quo and never occupied the region till 1984, when it was forced to move in to pre-empt Pakistan. It is time to revisit this Agreement and demarcate the area beyond NJ 9842 keeping principles of statutory interpretation, cartography and international law in mind to resolve the Siachen impasse.

Amit Paul is the author of the book ‘Meghdoot: The Beginning of the Coldest War’ which tells the story of how and why India ended up on top of the Saltoro Ridge. He is based in Gurugram and can be reached at amitkrishankantpul@gmail.com.

(Edited by Prashant)