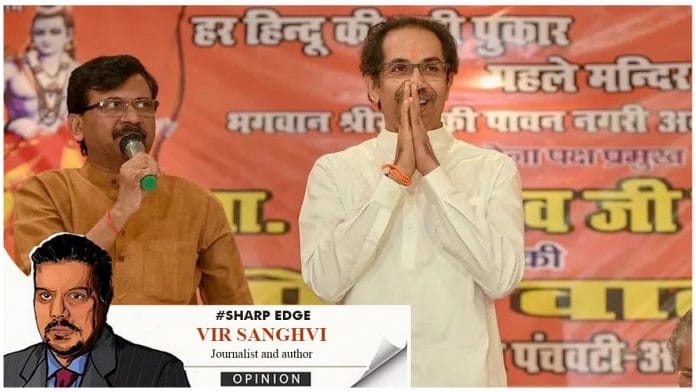

The news that the Shiv Sena parliamentary party has split and that a majority of MPs may desert Uddhav Thackeray comes as no surprise: After all, the majority of the legislature party in Maharashtra also abandoned Uddhav and went over to the Bharatiya Janata Party-supported faction.

And while, on one level, it is all about realpolitik, benefits for MLAs and greed for power, the implosion of the Shiv Sena also poses a more fundamental question: Is there less and less room in our country for a party that is not based on grievance?

These days, successful politics seems to be all about capitalising on grievances. Just listen to BJP supporters and their surrogates going on about how Muslims oppressed Hindus in the medieval era and how the time has now come for Hindus to avenge themselves on the “descendants of the Mughals.”

Also Read: Not Shinde vs Uddhav, Shiv Sena has an identity crisis. Choose Hindutva or get a makeover

Shiv Sena—a party found on grievances

The Shiv Sena has always been, at its core, a party founded on grievances. In 1967, when the Sena first came to prominence, its founder Bal Thackeray called for Maharashtrians to stand up for their rights, which were being eroded in the city of Bombay (as it was before Thackeray changed the name).

At that stage, Maharashtra had only been in existence for seven years. Till 1960, it had been part of the old Bombay state, which included much of what is now Gujarat. One of its most powerful Chief Ministers was Morarji Desai, who was a proud Gujarati. The creation of Maharashtra was preceded by a popular movement/agitation whose leaders Thackeray revered.

One of the Shiv Sena’s original complaints was that even though Maharashtrians now had their own state, they were still economically subjugated by Gujaratis. Besides, people from all over India (they meant South Indians) had come to Bombay and taken jobs that should have been given to Maharashtrians.

Thackeray’s movement was unapologetically violent. He made no excuses for the violence his supporters engaged in, arguing that they had no other alternative. He took the same position in the 1990s when the film Bombay showed a character, clearly based on Thackeray, regretting the violence of the riots that tore the city apart. “Regret? Why should I regret? I regret nothing,” he told me proudly.

And indeed, the Shiv Sena came to public attention only because of the violence. A Shiv Sena bandh meant anyone who dared defy the Sena’s dictates was attacked, cars were destroyed, shops damaged and their owners assaulted, and so on.

All this was originally justified in the name of Maharashtrian rights. Contrary to the impression the Sena gave in later years, it was not necessarily anti-Congress when it was founded. A cynical version has it that Thackeray was encouraged by Maharashtra Congress bosses such as S.K. Patil and V.P. Naik to found the Sena. They wanted him to fight the rise of Communist-led trade unions in Bombay. And indeed, Thackeray’s early statements were openly anti-Communist, and there were violent clashes between the two.

In 1967, when V.K. Krishna Menon stood as an independent against the official Congress candidate in the Lok Sabha election, the Sena served as the stormtrooper wing of the Congress. Arguing that Menon, a Malayali, had no place in Maharashtra, the Sena’s thugs beat up Malayalis in his constituency. Thackeray’s rhetoric was consistently full of attacks on South Indians: “They should go back to Madras,” he declared, to the bemusement of many hapless Malayalis who had no links with Madras.

Also Read: Shiv Sena witnessing political Waterloo, just like JD(S), BSP, SP

Change in Thackeray’s approach

Thackeray’s views varied over time. He fell out with the Congress when S.B. Chavan became Chief Minister (Chavan was opposed to Thackeray’s original mentors within the Congress) but never wavered in his admiration for Indira Gandhi, backing her when she was out of power during the Janata Party phase.

The ‘Maharashtra-for-Maharashtrians’ stuff began to run out of steam in the 1980s, so Thackeray switched to a platform that targeted Muslims. He had very little affection for the RSS, which he regarded as an effete organisation of Brahmins and offered up a more muscular version of anti-Muslim sentiment. It was never very convincing (unlike the pro-Maharashtrian stuff, which he actually believed in) and he was reduced to saying things like “look at the names of criminals in the papers. Why are there so many Muslims? We don’t want these kinds of Muslims. We want Muslims like Syed Kirmani.”(Kirmani was then part of the Indian cricket team.)

He proved his credentials as a defender of the Hindus in the 1990s when the Sena played a leading role in the Mumbai riots. (“We were attacked. We had to fight back,” he told me). After that, the ‘Maharashtra-for-Maharashtrians’ stuff took a back seat (though it never actually went away) and he acted as though he had done his bit when he changed the name of Bombay to Mumbai.

After Thackeray died, the Shiv Sena had two choices. It could stick with Thackeray’s politics of grievance and keep looking for targets or it could reinvent itself as a responsible political party. In some ways, these choices were mirrored by a personality conflict. Raj, Bal Thackeray’s nephew, tried to cast himself as his uncle’s successor, while Uddhav, Bal Thackeray’s son, took a more responsible, less hate-filled approach. Eventually, the Sena went with Uddhav and began a more peaceful, mature phase.

Also Read: Shiv Sena was hated by Indian liberals as extremist Hindutva party. Now, it’s their darling

RSS-BJP-Shiv Sena politics today

Contrary to the impression that the BJP is now trying to give, the Sena and the BJP were never natural allies. They tied up for electoral purposes only because Pramod Mahajan was able to persuade a reluctant Thackeray that an alliance represented his best hope of taking the Sena off the streets and into office. Even then, Thackeray was clear. The Sena would be the senior partner. The BJP could run the country. But he would run Maharashtra.

All this was before the rise of the Modi-Shah combine, who offered up exactly the sort of muscular Hindutva that Thackeray had criticised the RSS for not believing in. And this BJP was not content to play second fiddle in any alliance.

There are various explanations for why so many of the Shiv Sena’s MPs and MLAs have gone with the BJP in the current battle. One reason that is often advanced, is the lure of money. But there is also a second, more important factor. In today’s India, it is easier to function on the basis of grievances. Find an enemy, target a community and you will win public support.

That is what the BJP was offering: Hindutva politics. Uddhav, on the other hand, was only offering a promise of good governance. Eventually, many of his supporters decided that this wasn’t enough. They wanted the identity politics (of one sort or another) that Bal Thackeray had based the Sena’s foundations on.

This remains the kind of approach that many Shiv Sainiks are most comfortable with. Uddhav tried at the very end to change track but it was too late to embrace Hindutva. But by then, the BJP had broken his party.

So the Maharashtra drama is partly about the BJP’s need to run every state. But it is also about the change in Indian politics: Things go easier if you pick the politics of division, if not of hate. Moderation can be a path to nowhere.

The author is a print and television journalist, and talk show host. He tweets at @virsanghvi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)