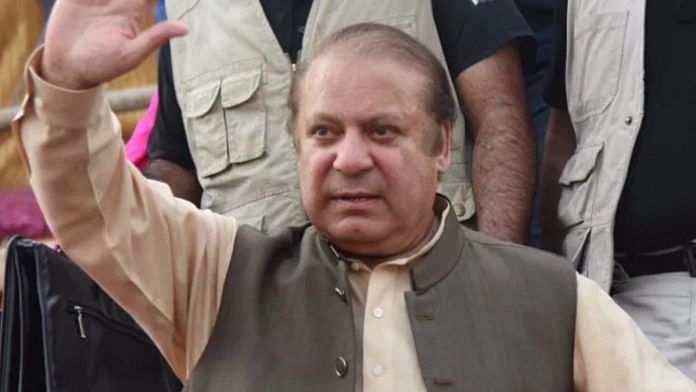

Zero, the scoreboard at the Karachi Gymkhana read. The gentle winter sun kindled the flush of shame that coursed through the young opening batter, as he began the long march back to the pavilion. Fifteen days short of his 24th birthday when he made his First Class debut for Pakistan Railways on 10 December 1973, Nawaz Sharif had seemed set for great things. Flying down from Islamabad to play for the Lahore Gymkhana, an entourage of retainers and sidekicks in tow, Nawaz had been hailed in local newspapers for his long string of pearl-like centuries in club-level matches.

“The [to-be] prime minister was undoubtedly helped by the choice of umpires,” the journalist Peter Oborne has written—but no one had been impolite enough to tell Nawaz that. His debut First Class match was also his last.

Earlier this week, the former PM’s daughter, Maryam Nawaz, took over as Chief Minister of Punjab. Like its coalition ally, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) is handing power to a new generation. The PML-N has shaped the country’s political destiny for decades, but its prospects are increasingly unclear. Although the PML-N had the unconcealed support of Pakistan’s political umpire—its military—in the just-concluded elections, independent candidates who back jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan emerged by far as the largest bloc.

Nawaz was elected as Pakistan’s prime minister three times—and each time pushed out of office by the military before completing his term. His failure, though, cannot be blamed only on the Generals’ toxic hold over Pakistan. As the PPP had done—and Imran would in his turn—Nawaz encouraged corruption, undermined democratic institutions, and collaborated with Islamists.

The rise of team Sharif

For decades, Nawaz seems to have sought to erase the stain inflicted at the Karachi Gymkhana. Imran Khan, then national team captain, has written that Nawaz appointed himself captain and insisted on opening the batting in a warm-up match with the West Indies ahead of the 1987 World Cup. Facing the world’s most feared pace attack, test batter Mohammad Nazar “wore batting pads, a thigh pad, chest pad, an arm-guard, a helmet and reinforced batting gloves.” Nawaz took the crease in pads and a floppy hat, apparently oblivious to the danger posed by cricket balls hurtling toward him at speeds upwards of 140 kilometres per hour.

“I quickly inquired if there was an ambulance ready,” Imran remembered. Fortunately, fast bowling great Patrick Patterson’s second ball ploughed into the stumps; the only injuries were to his ego. Later that week, though, Nawaz succeeded in scoring a single run in a warm-up match against England, before being bowled out by Philip DeFreitas. The progress might have been small, but it proved a good omen.

Led by his father Muhammad Sharif, Nawaz’s family had moved from a village near Amritsar to Lahore after the Partition. The historian Ayesha Jalal has recorded that western Pakistan’s economy was dominated by just eight large feudal families. The modernisation process set in place by Field Marshal Muhammad Ayub Khan, though, created space for families like the Sharifs to prosper. Through the 1960s, anthropologist Rosita Armytage writes, they set up several industrial units, including ice-making plants and a water pump factory.

Even as Nawaz stepped out to bat at the Karachi Gymkhana, his family had become mired in an existential crisis. In 1972, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto nationalised the steel industry, in pursuit of what he called Islamic Socialism. The Sharif family lost its crown jewel, the Ittefaq Steel mills.

Like other members of the fledgling industrial bourgeois, Muhammad Sharif understood that political power was needed to protect his interests. Nawaz was pushed into provincial politics and joined Air Marshal Muhammad Asghar Khan’s Centrist Tehreek-e-Istiqlal. Later, under military ruler General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Nawaz became chief minister of Punjab, at the head of a coalition of the religious Right.

Following General Zia’s death in 1988, months after the World Cup, Nawaz was recruited by the military to lead the Islami Jamhoori Ittehad, an alliance of his own party, the Jamaat-e-Islami, the Jamaat-e-Ulema-e-Islam and the Jamaat Ulema-e-Pakistan. “The military,” political scientist Vali Nasr records, “would defeat the PPP and reproduce Zia’s Islamisation order through the democratic process.” In 1990, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto was evicted from office, and Nawaz was installed in her place.

Following his rise to power, though, Nawaz sensed there was an opportunity to dismantle the military’s hegemony. In 1993, President Ghulam Ishaq Khan appointed General Waheed Kakar as Pakistan Army chief, superseding Lieutenant-Generals Rehm-Dil Bhatti, Mohammad Ashraf, Farrakh Khan and Arif Bangash. The Prime Minister had hoped to appoint a pliant figure instead, and, according to Jalal, began buying top military commanders. This was a mistake; Nawaz proved unable to take on the bowling, and was forced to resign by General Kakar.

Also read:

Keeping the faith

Like Nawaz, Pakistan’s cricket team had struggled since 1987. General Ali Akbar Khan, Imran’s cousin—later accused of embezzling $2.7 million that he had stashed in illegal foreign bank accounts—gave the captain a free run. This encouraged factional feuds inside the team, tearing it apart.

Following a series of disastrous matches in the 1992 World Cup, though, Imran succeeded in leading the team to an improbable triumph. It was exactly at the time Nawaz was evicted from office, Imran writes in his autobiography, that the cricket star began to consider running for office, on an anti-corruption platform.

Even though Imran and Nawaz were to become implacable foes, their political positions were indistinguishable. Imran’s promise to build what he called an “Islamic welfare state” was borrowed verbatim from a speech Nawaz gave to Parliament in August 1998. Nawaz had proposed a new law to “implement complete Islamic laws where the Quran and the Sunnat are supreme.” The law would have obliged the government to enforce prayers five times a day and collect religious tithes. Nawaz sought peace talks with jihadists in 2010, just like Imran.

This rightward march of Nawaz’s government was driven by his need to accumulate power, as he did battle with the army. Following a public call made by General Jehangir Karamat to set up a National Security Council—and thus give the army an institutional say in decision-making—Nawaz sacked his military chief. Nawaz appointed General Pervez Musharraf, who he considered a political lightweight, in place of Karamat. Nawaz’s Islamic legislation—and reported plans to declare himself Emir, like Taliban chief Mullah Muhammad Omar—were intended to win the support of the religious Right, too.

Within months, though, Nawaz and his new army chief were clashing over Pakistan’s India policy and terrorism. General Musharraf used jihadists to undermine Nawaz, and two attempts were made on the prime minister’s life. Following the Kargil war, Nawaz hit back, jailing political opponents and journalists, a campaign which ended with a botched attempt to depose General Musharraf.

Like his first attempt to push back against the military, this second effort ended in disaster. Nawaz was deposed in a coup, imprisoned, and forced into exile.

To attribute Nawaz’s stances simply to tactical posturing, though, is misleading. Like him, his wife Kulsoom—who died in 2018—seems to have held deep Islamist beliefs. In speeches she made after her husband was exiled, Kulsoom claimed the government was deposed “to end the Kashmir jihad and shut down religious seminaries.” And like Imran would last year, she blamed the government’s sacking on “conspiracies by non-Muslim countries.”

Also read: Pakistan Army’s problems are far from over. Imran Khan is both a force and a headache

A grim endgame

Even though he never got the opportunity to bat a second innings in 1973—Pakistan Railways crushed Pakistan International Airlines’ B-team by an innings—politics gave Nawaz a third chance. Following a political deal that ended General Musharraf’s rule, Nawaz Sharif contested elections in 2013. This time, he allied with jihadist groups like the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, responsible for large-scale killings of Shia Muslims. Leaders of the PML-N campaigned alongside jihadist leaders ahead of the elections, while the Tehreek-e-Taliban attacked its secular opponents, like the Awami National Party and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement.

The Pakistan Army had accepted Nawaz’s return, infuriated by an alleged PPP attempt to recruit the United States government to dismantle military primacy. Four years later, though, Nawaz would yet again be bowled out by the military, amid bitter differences over his efforts to make peace with India. Imran, who succeeded him, was chased off the throne in turn.

Even as Maryam railed against Imran for using religion as a political weapon, the PML-N has levelled charges of so-called blasphemy against its opponents, too—empowering extremists in a country already torn apart by violence. During his last tenure, PM-nominee Shehbaz Sharif even tightened Pakistan’s controversial blasphemy laws, which have placed dozens of innocent people on death row. Safdar Awan, Maryam’s husband, publicly supported Mumtaz Qadri, who was executed in 2018 for the blasphemy murder of Punjab governor Salman Taseer. Earlier, Awan delivered a speech assailing the persecuted Ahmadi minority.

Like the Bourbons, Pakistan’s political elite have shown that they have forgotten nothing, and learned nothing. Even as he tenaciously pursued electoral power, Nawaz helped unleash forces that have rotted Pakistan’s democracy from within. His successors show no signs that they’ll be able to lead the country away from its ugly sunset.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)