Following the path of the great Silk Road caravans Leh to Yarkand and Kashgar, a small Indian Army patrol marched east in the summer of 1962, climbing up the Kugrang Tsangpo river, through the ancient camp-grounds at Katajila, then over the 5,500-metre Changlung La pass, to a place almost no one had heard of: the Galwan Valley, named for a clan of master thieves who trafficked stolen horses from Kashmir into Turkestan, using its savage terrain to conceal their movements.

Bhola Nath Mullik, India’s spy chief, had flagged the significance of the valley the previous year, in a top-secret letter: “If the Chinese commanded the Galwan Valley, it would give them easy access to Skardu, Gilgit, etc., and our routes to Murgo, Daulat Beg Oldi, Panamik would be cut.”

Fearing the worst, troops were despatched to Galwan, with catastrophic results. Now, as New Delhi grapples with the worst crisis on its eastern border since the war of 1962, it’s vital to learn the right lessons from the story.

Also read: China’s Land Border Law is more sinister than it lets on. India needs a course correction

China’s message is clear, India’s isn’t

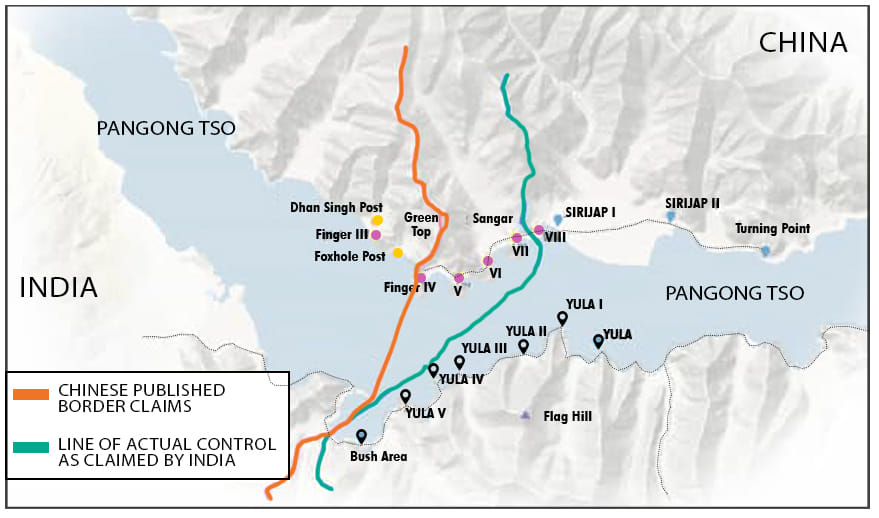

Last week, news broke that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is building a bridge across Pangong Tso, linking its base at Sirijap to the south bank of the lake. The bridge will drastically reduce the distance the PLA needs to traverse to reinforce its positions south of Pangong, an area where Indian troops have traditionally enjoyed a tactical advantage.

Add to this propaganda videos of the PLA parading in Galwan, and the rising tide of anti-India polemic on China’s social media, the message is clear: Beijing has no intention of allowing the LAC crisis to melt away come spring.

Less clear is how New Delhi ought to be responding. For much of 2021, New Delhi has sought to buy time with a series of less-than-happy compromises.

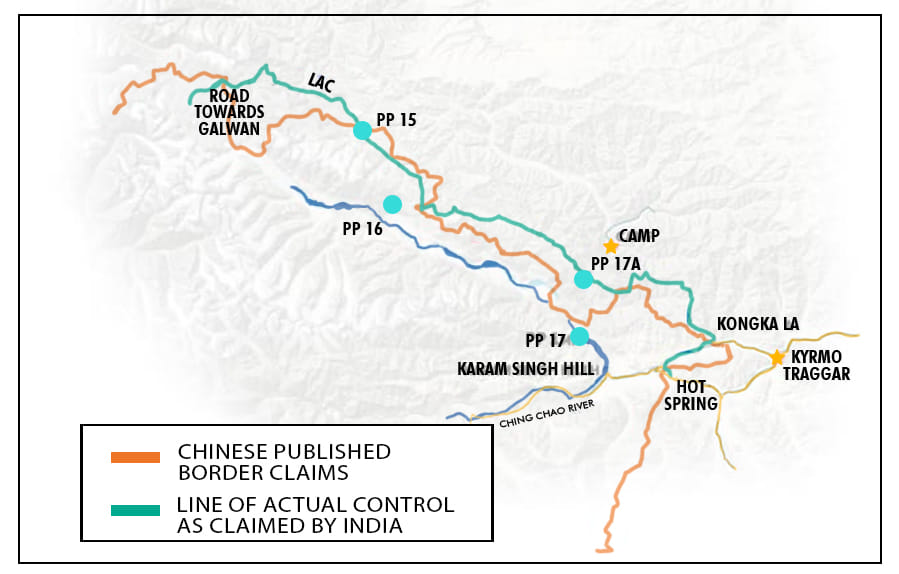

Troop disengagement in the Gogra area involved Indian troops falling back to their permanent positions at Point 17, at the confluence of the Changlung La stream and the Kugrang river. In turn, the PLA pulled back to semi-permanent positions some two kilometres north-east of the LAC. India also suspended patrolling between Point 17 and 17A.

Last year, China reasserted border claims made by then-Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai in 1959. In the 1960 discussions by government experts on border issue, China claimed the border “followed the watershed between the Kugrang Tsangpo river and its tributary, the Changlung”. The border, China’s negotiators precisely claimed, crossed the Changlung at Longitude 78°53’ East, Latitude 34°22’ North—in other words, south of Point 17A.

The Gogra agreement not to patrol up to Point 17A means India, for all practical purposes, now recognises China’s new claim that the LAC lies south of Point 17A, at 78°53’E,34°22’N, territory the PLA has never held.

In Pangong, India has had to make similar concessions. New Delhi has agreed not to patrol between Finger 4 and 8, a series of ridges radiating along the north bank of Pangong. In the 1960 discussions, coordinates provided by China placed the LAC along Finger 7 and 8. In other words, the demilitarised zone created in February 2021 between Finger 3 and 8 lies in territory which China has acknowledged, in formal negotiations, to lie on the Indian side of the LAC.

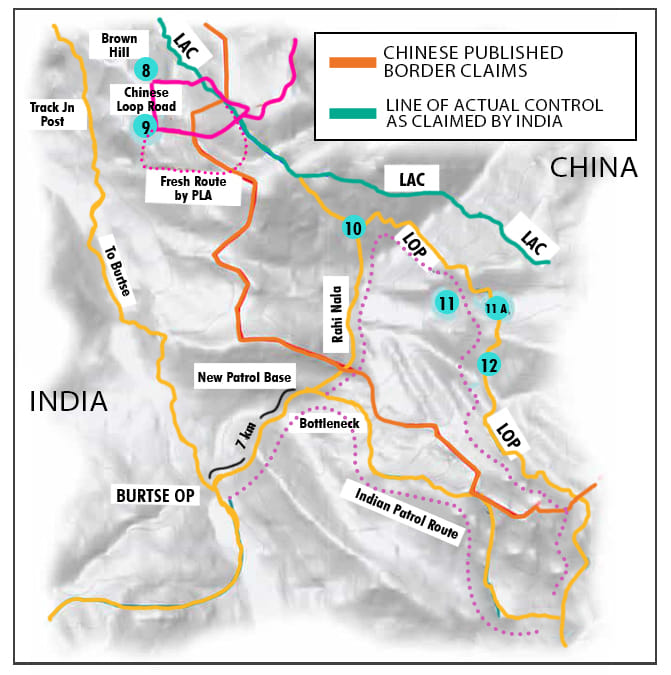

Any disengagement in the Depsang Plains, similarly, will likely involve the painful decision to give up patrolling to the arc from Point 10 to Point 13, in return for China pulling back troop positions that have built up east of the Indian post at Burtse—effectively giving up the right to physical assertion of the LAC.

Also read: Why the Chinese build-up at LAC will set stage for a permanent solution

An LoC-like situation brewing for India

This is all bad news for Delhi—but it’s far from clear that a more muscular posture will serve any useful purpose. The PLA’s modernisation is decades old; efforts to transform the Indian Army, by contrast, have wheezed and spluttered. There is a giant gap in spending — $178 billion is committed to the Chinese military compared with some $47 billion by India. In addition, China has invested giant sums in fixed asset creation in Tibet. In 2019 alone, it spent some $9.9 billion on roads, railways and fibre-optic lines.

Logistics experts have estimated the networks of rail and roads already in place could allow the PLA’s 76th and 77th combined-arms Group Armies to move up to seven division-sized formations into the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) inside a week, and over 32 inside a month. The PLA has all-weather road access to the 31-odd major passes across the LAC.

The worst-case scenario, then, would be for New Delhi to be drawn into a Line of Control-like commitment to defend each centimetre of its territory against a logistically superior adversary. Instead of seeking to match each PLA bridge, road or battalion, it needs to focus on long-term military capacity development and modernisation, even at the cost of territorial concessions.

The ghost of B.N. Mullik would likely make the case for doing just this. Early in July 1962, a PLA patrol discovered the Gurkha soldiers in Galwan, and cut them off. In October, a company of 5 Jat were flown in on Mi-4 helicopters to replace them—only to be overrun by an entire PLA battalion, as war broke out.

For developing such a policy, though, Prime Minister Narendra Modi will need to transparently communicate his dilemma to the public, and build a consensus on next steps—no small ask for a leader whose public image is built on machismo.

The author tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)