Privacy is a basic human right, and even criminals have those. To undermine this capacity because vicious, punitive justice sells on primetime TV debates is to tear through the foundation that this country.

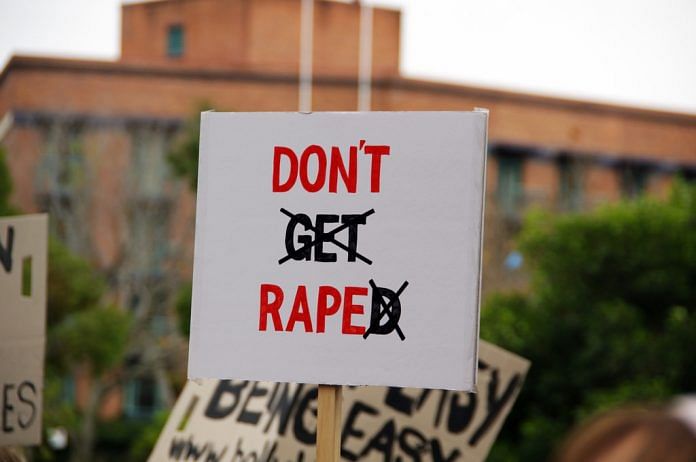

Indian governments, irrespective of the party helming them, have a history of knee-jerk reactions when it comes to appeasing public unrest. This tendency shines through most obviously in cases of public anger against incidents of sexual violence that capture the country’s imagination and bring people out on to the streets. We saw this in the aftermath of the 2012 Delhi rape case when Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013 was brought in. It quietened the anger long enough for people to move on to the next outrage.

And now, as always, history is repeating itself.

The idea of a sexual offender’s registry has been floating in India for a while now, and it finally came to fore with the Kathua and Unnao cases that rankled the country recently. On 13 May, the Ministry of Home Affairs floated a Request for Proposal (RPF) for the selection of a private agency that would create and host the registry across the country. This will lead to India joining the ranks of several countries that host such a database. While most countries limit the access to the registry only to law enforcement officials, the US allows full public access to theirs. India, as far as the RPF shows, will choose a middle path, with the names of the convicted offenders available to the public, while the list of those charge-sheeted and arrested being available only to law enforcement officers.

On the face of it, a registry sounds like a good idea. Shame is, simplistically speaking, a powerful motivator for good behaviour, and the idea that you can know if the people around you may be a danger to you might foster a sense of safety. But is that what will really happen?

We have no conclusive evidence of these registries working. The US has had these around for over 30 years, and research shows that they might actually be doing more harm than good. Two studies that came out in August 2011’s edition of The Journal of Law and Economics underscore this point. Amanda Agan, in ‘Sex Offender Registries: Fear without Function?’, states that these registries do little, if anything, to impact public safety. JJ Prescott and Jonah Rockoff, in ‘Do Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws Affect Criminal Behavior?’, underscore this point and, in fact, show that the limited number of repeat offenders seems to be more likely to commit sexual violence if their name is on the list.

The proposed Indian registry has an additional host of ‘features’ that make it an immensely risky endeavour. The ‘tiers’ it is divided in (which include ‘suspects’, ‘rapists known to victim’ and ‘gang-rapists, murderers, and those in positions of authority over the victim’) seem far removed from the realities of sexual violence in India. A quick look at the 2016 National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data will show that out of the nearly 40,000 cases reported in India, the victim and the accused were known to each other in almost 95 per cent of the cases. In nearly 10 per cent of the cases, the abuser was a family member. Considering the unequal, toxic, patriarchal family dynamics in India, it’s a near-miracle that these many cases were registered. Considering the incredible pressure on survivors to keep quiet and protect the ‘honour’ of their families, how many cases would see the inside of a police station when threatened by public shame?

It is also important to acknowledge the fact that the registry, much like death penalty for child rapists, also puts the survivor in mortal danger. Earlier, there was no reason to kill after the act of rape. Now, silencing the victim will be incentivised. These tiers also don’t make a demarcation for juvenile offenders. Considering our laws don’t have any clause of age proximity, it will be incredibly easy to criminalise young people having sex. We already have precedents for parents of girls accusing boys of rape in cases of consensual sex . This will make it worse.

Another feature is that of Aadhaar linkages for the database.

It’s a leaking, broken system that houses within it critical, sensitive information that can actively endanger people if it’s released. Imagine if someone knew everything about you, right from where you work to how you live. Now, imagine if that information is available to people who don’t always have your best interests at heart. This isn’t just a dystopian future, though. This is happening right now, and engaging something as sensitive as criminalisation with this information will spell unexaggerated doom for a country where the odds are already stacked against minorities and vulnerable communities. A democracy, by its very existence, champions the access of a citizen to a life of dignity, with constant, unfettered access to their basic human rights.

Privacy is a basic human right, and even criminals have those. To undermine this capacity because vicious, punitive justice sells on primetime TV debates is to tear through the foundation that this country and its systems of functioning claim to stand on. Surveillance can simply not replace better, comprehensive systems of justice.

It’s very easy to create a binary between ‘us’ and ‘them’, especially when it comes to rapists. It’s a human, visceral reaction to want the worst for people who commit such heinous crime. However, it is in times of such civic crises that we must pause and wonder if appeasement from the government’s end should be enough to dampen our outrage. We already have incredibly comprehensive laws in place, but the crux of our issues has always been the inability to execute them comprehensively.

We’re lulled into complacency by short-term, narrow-visioned policy hackjobs that do nothing but absolve the government of responsibility. In the volatile, difficult times we’re living in, we simply cannot risk paradigms that thrust already vulnerable communities into worse situations.

We must demand better implementation of laws, better investment in education, and better of our leaders. We must not, however, demand retributive justice that satiates our collective hurt through violence. Baying for blood like a lynch mob just undercuts our responsibility.

Harnidh Kaur is a poet and feminist.