Do you know what or where is K Songjang? How about Kwakta? Can you identify Dolaithabi? Would you know a Meitei from a Kuki and what separates them?

To tell you the truth, I knew the answer to only the last question before a tidal wave of violence and government apathy brought the others to the news headlines.

The Northeast state of Manipur has been witnessing ethnic clashes between the Meiteis and Kukis since 3 May. As of 25 June, the violence left 131 dead and more than 400 wounded. Nearly 50,000 people have been forced into makeshift relief camps, with a large contingent of local and central forces striving to maintain peace.

The enormity of the conflict caught everyone by surprise, including the media. ThePrint, and other organisations, had reporters on the ground almost immediately. None expected the flare-up to explode into a conflagration that would consume the state.

The primary difficulty faced by editors and reporters was simple in its complexity — ignorance. How do you convey the intricacies of a historical enmity that suddenly turned violent — and acquired the contours of a potential civil war — when few people even know where Manipur is on the Indian map?

Journalists and readers are familiar with communal politics in India — we instinctively recognise the underlying bloodied waters that run deep between Hindus and Muslims. However, the Meitei-Kuki divide, based on issues of majoritarianism, religion, land, migration, and identity, is a complete mystery to most of us.

ThePrint set out to unravel that mystery wrapped in fear for its readers — though not in full measure but substantially. And its correspondents answered all the questions I asked you at the start of this Readers’ Editor column.

Also read: Manipur is India’s gateway to East. But doesn’t get even half the political focus as Kashmir

The right answers

Kukis, Meiteis, and Nagas are the three main ethnic groups in Manipur. They are separated by geography — Kukis live in the large expanse of the hills, while Meiteis reside in the Imphal Valley — ethnicity, and religion.

K Songjang, a once Kuki-dominated village in the Churachandpur district, was razed by the N Biren Singh government in February on charges of alleged encroachment on protected forest land.

In Kwakta, located in the Bishnupur district, Meitei women formed a human blockade to express their resentment against the central security forces.

In Dolaithabi village on the evening of 3 May, 140 homes, mostly inhabited by Meiteis, were burnt down in the ethnic clashes.

Exploring the conflict

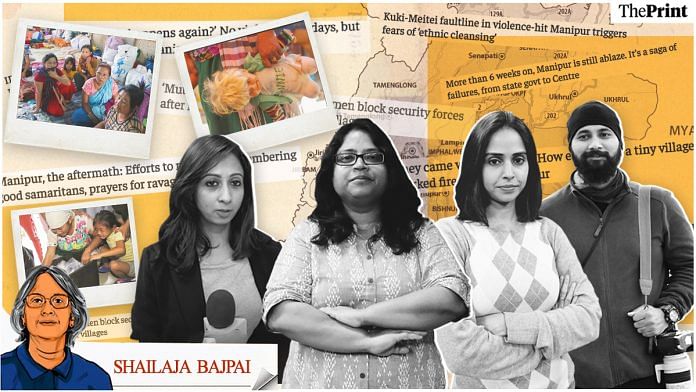

During May and early June, ThePrint’s Moushumi Das Gupta and Sonal Matharu from Delhi, along with Karishma Hasnat stationed in Guwahati, travelled through the strife-torn state — from the hilly homes of the Kukis to the Imphal plains where the Meities live.

“At the time, we didn’t know what was happening,” says ThePrint’s National Security Editor Praveen Swami. “And we didn’t have a clue as to why.”

The triggers for the ethnic violence and the subsequent events — the government’s response, deployment of troops, displacement of thousands, fresh clashes, and the devastation of lives — were well captured in the reports. You get a palpable feel and very real sense of the two communities lashing out at each other almost mindlessly.

“The current spate of tensions is centred on the Meiteis’ demand for Scheduled Tribe (ST) status, which, they say, is a bid to secure constitutional safeguards for the community,” wrote Das Gupta on 10 May.

But can that explain such extreme polarisation between the two communities? “In this case, the breaking news had to be contextualised. Otherwise, it doesn’t work,” says Nisheeth Upadhyay, Editor (Operations) at ThePrint. “It was crucial to give the larger picture because you couldn’t understand the events that unfolded without that.”

Also read: More than 6 weeks on, Manipur is still ablaze. It’s a saga of failures, from state govt to Centre

‘Overwhelmed’

In any conflict reporting, the incidents of violence and their human cost vie for equal, if not more, attention as the deeper, causal narrative. Reading ThePrint stories — there were more than 30 from Manipur in May — you become aware of this constant back and forth between cause and effect.

Hasnat reported on the sporadic violence on 28 April that would, within a week, turn into a nightmare for the state.

In March, she had reported on troubles in Myanmar that could impact the situation in Manipur.

And then there were reports that captured the deeper and more worrying fault lines. Das Gupta wrote about a bureaucracy divided along ethnic lines.

“In all my years of reporting, I have never seen anything like this,” she said. “We brought out the situation on the ground and the reality of the divide between the two sides. Perhaps we didn’t do enough on the majoritarianism and the targeting of tribals or the politics.”

Matharu explains why. “We were overwhelmed by news and information coming to us from all sides — it wasn’t always easy to step back and see the big picture. There was also a lot of propaganda, which you had to verify.”

For instance, it was impossible to confirm the allegations made by the Meiteis that the Kuki population had grown disproportionately due to illegal migration from Myanmar – there has been no census since 2011. “Data was an issue,” adds Matharu.

Hasnat was in Imphal when the violence broke out on 3 May. She travelled up to Churachandpur, the epicentre of the clash. “Land was one of the major root causes of this flashpoint, and I tried to convey that in the reports,” she says.

One missing link that I noticed was the political one. Although there are some BJP voices in the stories and quotes from protesting MLAs who came to Delhi with their complaints, it doesn’t go beyond that. You would expect the opposition — in this case, the Congress — to be vocal and a good source of information. “The opposition political parties didn’t come out and make themselves heard,” says Hasnat.

“The security angle, the violence, did get a bit overwhelming,” admits Upadhyay.

So, did ThePrint succeed in conveying the ground reality and what lies beneath? Yes and no.

Swami reminded me that it is in the nature of conflict reporting to first concentrate on day-to-day developments. “It’s difficult to have long conversations about other things when something is always happening around you,” he says.

Also read: ThePrint Ground Reports go beyond breaking news, tell stories that are being buried

Dictation, text messages, contacts

Not just politicians, ThePrint reporters also found officials and police unwilling to talk in a ‘developing situation’. The Kukis and Meteis, though, were “more than happy to talk”, according to Das Gupta. “People in some villages were mistrustful,” adds Matharu. “I had to win their trust and convince them I wasn’t a plant.”

By the time Hasnat and Das Gupta travelled to Manipur, an internet lockdown was already in place. This is another dimension to the reporting that is often missed when we look at a published report. Social media has made us impatient — we want the news even as it is being made.

But when you’re travelling, especially to remote areas where internet connections are invariably poor, how do you send back reports and long analytical pieces for publishing at the required speed? “Time is important in violent situations,” says Das Gupta.

Reporters and editors have to be inventive. Das Gupta used contacts in the state secretariat to send her pieces, although this was limited; Hasnat knew local reporters. They also sent stories sentence by sentence in messages. In Delhi, editors took dictation over the phone.

Under such circumstances, it’s tough to write big-picture stories on the phone and transcribe them while someone speaks.

The problem was even more acute when it came to sending photographs over the phone or the limited access to the internet. Those photographs by the reporters and Senior Photographer Suraj Singh Bisht showed us just how bad the situation was on the ground.

What might have helped readers understand the situation even better could be accompanying graphics and maps – for instance, a heat map of the violent spots.

Of course, it is very easy to be wise in hindsight. I read all the reports together—and at the end of it, I can honestly say that while I am not an expert, I do have a working understanding of what is at stake in Manipur.

It has left me wanting to know more…

Shailaja Bajpai is ThePrint’s Readers’ Editor. Please write in with your views, complaints to readers.editor@theprint.in

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)