Photos of filthy slums and poor children are aimed at shaking our conscience but take agency away from those photographed.

Alessio Mamo faced severe backlash for his photo series ‘Dreaming Food‘. But it’s just the latest instance of poverty porn in a long line of UNICEF, National Geographic, Save the Children and others who have been doing it for decades.

Mamo’s pictures were recently featured on the Instagram account of World Press Photo.

Mamo tried to justify his photos by saying, “The concept was to let Western people think, in a provocative way, about the waste of food.”

True, but what he did was unthinking. He asked poor people in India to dream about their favourite food while he placing fake food on a table in front of them in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

In the process, he took away the agency and dignity of those he photographed. Not to mention the utter insensitivity of the project.

What is the world’s obsession with poverty porn?

A quick search on the internet for poverty gives you a wide range of pictures – mostly of Indians, Africans, and the occasional poor white man feeling sorry for having a single dollar left in their wallet.

But poverty porn is not just confined to photographs.

It is “any type of media, be it written, photographed or filmed, which exploits the poor’s condition in order to generate the necessary sympathy for selling newspapers or increasing charitable donations or support for a given cause.”

Poverty porn started with charities and non-governmental organisations milking sympathies through advertisements, campaigns and videos to get donations. A trend that continues today. They mastered the language of poverty porn.

Common tropes include black and white photos of malnutritioned children, dirty slums, helpless mothers, and of course, emotional music cues accompanied by an American or British man narrating the story.

Save the Children, for example, released a video of an African mother giving birth to a stillborn baby. The baby eventually cries and the video ends with, “Basic training for midwives can help end first day deaths. TEXT BORN TO 70008 to give £7.”

The strategy seems to be absolutely on point for it plays on the guilt of the privileged, and to free themselves of this gut-wrenching guilt, they must make donations to charities.

Does poverty sell?

It does. In millions.

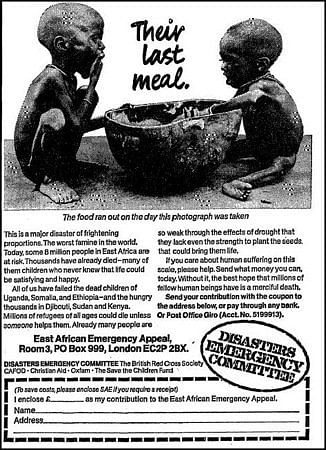

Back in the ‘80s, the term poverty porn was being used in advertisements that were guaranteed to grab eyeballs of the world, like this one.

This ad from the UK charity Disasters Emergency Committee for the 1983-85 famine in Ethiopia brought in $23 million between 1980 and 1984.

Every year several organisations get thousands of dollars in donations thanks to these stereotypical images.

We have all been victims of poverty porn and have, in one way or the other, contributed to it, or looked past it. The problem lies in overlooking it as just another pop culture term, and not as a dangerous method.

Most of these photos and videos temporarily shake our collective conscience and is quickly forgotten thereafter (whether or not we donated money or not).

How do we deal with it?

Do images that thrive on the vulnerability of those who are photographed, work better than images that would be more positive and uplifting?

Danish aid worker Jorgen Lissner wrote in an article for the New Internationalist in 1981, “The starving child image is seen as unethical, because it comes dangerously close to being pornographic…it exhibits the human body and soul in all its nakedness, without any respect for the person involved.”

Remember Kony 2012? The documentary that was directed by Jason Russel became one of the most viral videos on the internet but received a lot of scrutiny worldwide. Not only was it criticised for making the situation in Uganda appear extremely simplistic and something that could be solved through talent, art and protests held outside the White House, but it championed the white saviour complex.

Rosebell Kagumire, a Ugandan journalist, in her hard-hitting response to the video said, “If you are showing me as someone who is voiceless and hopeless, you have no space telling my story, you shouldn’t be telling my story.”

Ethiopian-American novelist Dinaw Mengestu in an article wrote that “it’s a distortion, or at worse, a self-serving omission of the extensive efforts made over the past decade by the UN, US, Ugandan and South Sudanese governments, and numerous religious and civil organisations across Uganda, to bring Kony to justice.”

Simply feeling like “making a difference” or knowing of something that’s happening in the world and hence believing that taking any action will obviously be good does way more harm than helping the cause.

The poor are not props, and taking advantage of their silence and oppression only brings out the arrogance of visual language.

It is often easy to say that “the underprivileged smile when they are asked to be clicked because they are cool” (that too in a TEDx Talk) without delving deeper into the issue and understanding that the system of poverty porn has thrived because we remain complacent and find ways of being rid of our temporary guilt through minimal donations.

Brilliant article Food for thought