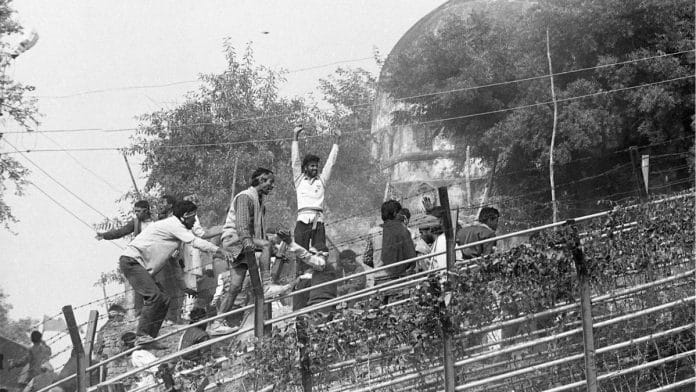

Two photographs from contemporary Indian politics are etched in my mind. One is of the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition. And the other is from the 2019 anti-CAA protests at Shaheen Bagh led by old women. The images couldn’t be farther apart. And the messages they send to me are diametrically opposite. One attempted to pin me down solely as a Muslim. The other emboldened me in my refusal to be identified.

Through these two photographs, I trace the shifts in my public and social identity.

I was only a few months old when the first photograph was taken. My hometown, Jamshedpur, is a quiet, sleepy town that has often been awakened by rude shocks of sporadic violence. But the violence after the destruction of the Babri Masjid had a unique character altogether. My elders always get uncomfortable speaking about it and I desist from probing them further. Apart from the heavy silence, the photograph has shaped my social identity: I always have to carry the baggage of that hyphenated existence: the Indian-Muslim.

The decrepit monument in that photograph is of no consequence to me, but the memory of men wielding sticks and weapons atop its domes signifies an aggression; that they need to heal from a medieval ailment in a democracy.

But does this ‘correction’ of a supposed historical wrong justify the violence on people who had no stake in that 500-year-old building?

That photograph does not only contain the premonition of physical violence but also a symbolic one. It imprisons me in a vulnerable space forever. I look at that photograph and how it disfigures me. It makes me wary of certain gatherings, and on certain festivals. It forces me to remember the violence that I would rather forget and that can recur very easily.

My usage of the first person pronoun here does not project only my personal thoughts but also voices my socio-political existence. Separated from the average Muslim in terms of privilege, I am nonetheless, united with them in the wide public sphere. The painful memory of that photograph has spread its tentacles deep into the future and continues to shape my present.

Also Read: Unseen photos of how Babri Masjid demolition was planned and executed in 1992

Resistance to injustice

If that one photograph is an assertion of power, then the Shaheen Bagh photograph is a resistance to that power. It is a teachable image in the sense that it infuses me with the hope that injustice can be countered. If power is centralised, then resistance, even when decentralised and in pockets, is resistance nonetheless.

If the photograph from 1992 brings pain and suffering, then the photograph from 2019 encourages my resistance to it.

In the bleak December of 2019, braving the winter cold, women blocked the road in protest of a citizenship law which they deemed draconian. The face of the protest was an octogenarian woman, affectionately referred to as Bilkis dadi.

The name Bilkis symbolises resistance on two fronts: one who carried that name fought a two-decade-long arduous battle to bring her rapists to justice; another stood in the cold against CAA-NRC.

What makes the photograph iconic is the fact that against a mighty state, an old Muslim woman stood for her rights. Often considered demure by the Right-wing, seeing a Muslim woman stand her ground amidst barricades and armed police fills me with hope and pride. And it is this glimmer of hope in the darkness of despair that matters.

I look at that photograph and Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge, which became the anthem of the protest, and it makes me realize that injustice no matter how great can always be resisted.

The two photographs bookend my understanding of India and my place in it.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

the consequences exists even for Hindus dear, after this incident the police open fired on these people. more than 10 people were reportedly killed on scene.

numerous other were arrested, and in their arrest sheet their crime was written “Ram Bhakt”.

also your hypocrisy on choosing the 2nd image is utterly laughable, India is surrounded by 3 of the MOST POPULATED MUSLIM COUNTRIES. and hence is NOT obligated to take Muslim refugees, theese countries are filled persecuted minorities since Independence that only have India as a last resort.

But of course you will conveniently ignore these points as they don’t fit in your narrative.

reply with even one proper counter argument if you have the balls to buddy.