The central government seems believe the raids will help contain political unrest and erode the public credibility of the Hurriyat leaders.

The National Investigation Agency (NIA) has run amok in Kashmir. Political leaders, activists and businessmen, who are believed to be challenging Delhi’s rule in Kashmir, and close to the Hurriyat, are being investigated for “political conspiracy, collusion with Pakistan and money laundering.”

Ostensibly, the central government believes these measures will help it contain the political unrest in Kashmir. It seems to also believe that these measures will erode the public credibility of the Hurriyat leaders just as such measures did to leaders like Sheikh Abdullah, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed and G.M. Shah.

There is a pattern to this sort of allegations of corruption by Delhi in Kashmir’s political history.

In 1953, barely six years after Kashmiri leader Sheikh Abdullah had embraced the idea of a secular and democratic India, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru removed him from power, arrested and imprisoned him. The government counsel pleaded before the court that Abdullah and his companions had “collaborated with Pakistani officials to overthrow the state government through violence.”

The court was told that Abdullah’s wife Begum Akbar Jehan and political workers had “received money from Pakistan.” Abdullah remained in jail for 11 years.

As the political situation in Kashmir became unmanageable, Delhi dropped all charges against him in 1964. After his release, he assumed power again.

Meanwhile, the man who had helped overthrow Abdullah and had governed Kashmir for eleven years – Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed – was arrested with six associates. Seen by Delhi as a “hurdle” to extending Articles 356 & 357 of Indian Constitution in the state, he met with the same fate as Abdullah.

An inquiry commission, headed by Justice Ayyangar, was formed to investigate Bakshi’s “corruption and misuse of power”. Bakshi and his family renounced politics for good.

In 1985, G.M. Shah was perceived to be ineffective in containing political unrest. A memorandum – known to be a Delhi’s brainchild – detailing his “abuse of power and corruption” was submitted to the former President Giani Zail Singh and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. The memorandum paved the way for his removal.

It is 2017 today.

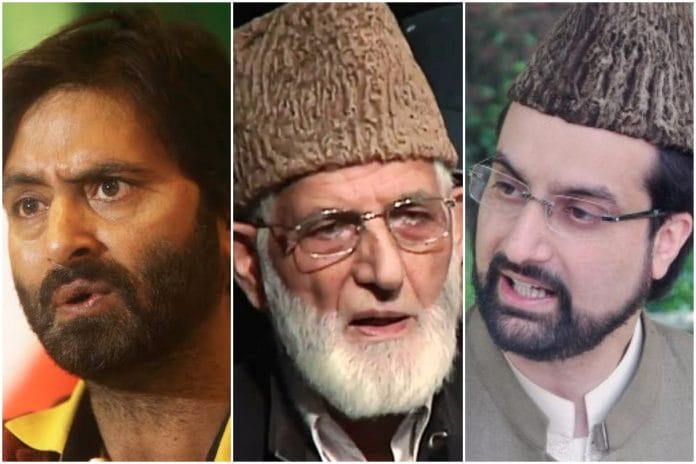

The top three leaders of the Hurriyat Conference – Yasin Malik, Mirwaiz Umar and Syed Ali Geelani – were planning to hold a dharna in front of the NIA office in Delhi and court arrest on 9 September. They were detained even before they could board the flight from Srinagar.

So will history repeat itself? Will this exercise give Delhi elbow room to push its agenda in Kashmir? Or will things just go horribly haywire?

There are two views in Kashmir today about the NIA crackdown. One view is that it is a precursor to the scrapping of the Article 35 A of the Indian Constitution – a measure designed to bulldoze the opposition. The other one is that it is a decisive move by Delhi to deny Pakistan the political leverage it has enjoyed in Kashmir.

Whatever the reason for it, the big questions are: Will this crackdown erode the credibility of the Hurriyat Conference leaders? Or will it create greater space for parties like the National Conference and the PDP? Will it pave the way for alternative, and possibly far-right political forces, to occupy the political centre in Kashmir?

The first two scenarios are unlikely to occur. While it is understandable that certain individuals engaged in money laundering, tax evasion or poor tax documentation will be affected by this exercise, the most ominous outcome could be a political vacuum. So, who could fill that vacuum?

It is a known fact that Kashmir’s political parties/formations have been receiving financial support from India and Pakistan ever since 1947. India’s former RAW chief, A. S. Dulat, has candidly stated that in his book “The Vajpayee Years”.

But the expectation that this exercise will end up throwing the same results as witnessed in 1953 or 1964 is likely to be proved wrong. The situation in Kashmir today is very different. The political gulf between the idea of India today and Kashmir’s quest for dignity and justice is wider than ever before. The politically assertive Kashmiri youth find it hard to reconcile to a situation in which they face perpetual humiliation and indignity.

Pushed to the wall, and bereft of a political voice, another generation of young Kashmiris could be pushed towards a far-right worldview and insurgency. That would be a tragedy.

An approach towards conflict resolution that banks only on the instruments of militarism and insurgency will be counter-productive for both Delhi and the people of Kashmir. Sooner, rather than later, Delhi and Islamabad will have to return to the negotiating table for the sake of durable peace in Kashmir.

A slide into the unknown in Kashmir will serve nobody’s interest – neither India’s, nor Pakistan’s, and definitely not Kashmir’s.

Negotiating with Pakistan? Will it ever yield results? Will Pakistan stop at anything less than complete separation?

This will help india in general and kashmir in particular.