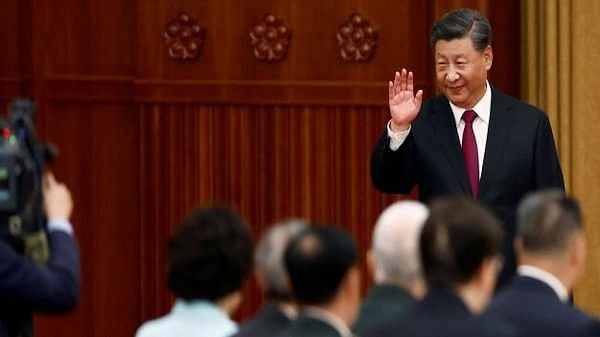

During his speech at the 20th Chinese Communist Party conclave, President Xi Jinping referred to “New China” without revealing much about its specifics, objectives and final goal. China experts everywhere must be busy reading between the lines, analysing the minute-to-minute footage of the events and deciphering the meaning of the signals. Chinese leaders convey their thoughts more in signals and hints than through transparent straight talk. New Delhi should start reading the signals emanating from Beijing, especially about “New China”, the mention of 1962 and the third time president honouring a People’s Liberation Army soldier slain in the 2020 Galwan Valley clash.

During his visit to a PLA museum, Xi refers to how the CCP has been leading the armed forces in enhancing its ‘political loyalty’ and intensifying military training for better combat readiness. Little wonder that the museum includes exhibits of the 1962 War blaming India for it, a panel honouring a PLA soldier killed in the Galwan clash, and a “Karakoram stone” asking visitors to press a button to show their support to the PLA troops along the border. Xi refuted claims that China has an expansionist agenda and emphasised having a strong PLA for the country’s security and peaceful purposes, not for conflicts. But he did warn of “dangerous storms” on the horizon. New Delhi should learn to read the tea leaves.

The third term for Xi may not be as rosy and easy as the first and second terms. During Xi’s second term, the US under Donald Trump had withdrawn from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and left an economic void in Asia to be filled by China. But now, as Xi takes stock of the domestic and global situation, his party, economy, and Chinese society could turn into his adversaries, not to speak of his ideological opponents.

Also read: It’s a myth IAF wasn’t used in 1962 War. Helicopter and transport fleets were deeply involved

Total control

During the run-up to the 19th CCP Congress in 2017, where Xi Jinping was re-elected for a second five-year term as the party’s Secretary General, an unprecedented publicity blitzkrieg about the “Five Years of Sheer Endeavor” credited Xi with everything – from PLA modernisation to success in space programmes invoking memories of Chairman Mao.

Mao, with his larger-than-life stature, was a ruthless leader who was more feared than revered, who introduced the element of a personality cult, implemented the disastrous ‘Great Leap Forward’ project resulting in mass starvation and purged many of his colleagues and distractors including Xi Jinping’s father Xi Zhongxun. Incidentally, Xi Jinping’s father was among those who resisted Mao’s appropriation of the success of the revolution and his distortion of the Communist Party’s history. But then, Mao had outgrown the CCP.

Once Xi Jinping’s second term was confirmed, party insiders began to notice the change in his working style – Xi was ‘deviating’ from the collective leadership model introduced by Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping. Deng introduced a collaborative leadership arrangement in the CCP in the 1980s along with amendments in the rules, which sought to limit the terms of leaders in office and proposed retirement age for politburo and Standing Committee members.

Having tasted power and realised the bitter truth of the Communist system that absolute power begets power, Xi Jinping decided to jettison Deng’s path and instead walk on the path of Mao. He, therefore, had to weed out the detractors, find an alibi like an anti-corruption drive to purge prospective successors and detractors and establish his supremacy in the party, political set up and the power circles like the PLA and technology and financial institutions.

Visuals of the former president of China, Hu Jintao, seated next to Xi, being escorted out of the final session of the 20th Communist Party Congress, sent a strong message to this effect. After all, Hu Jintao, the last Samurai against authoritarianism, was part of the decentralisation process.

Now, the CCP seems to be under the complete control of Xi Jinping. But authoritarian rulers and dictators are fully aware of the dangers of personality cults and riding a tiger. Xi Jinping first conducted a tour of Yan’an with his team after assuming office to impress upon them the need and importance of the party, which he ruthlessly subdued. In the conducted tour of the caves in Yan’an, Xi Jinping reportedly lectured at length about the 7th Party Congress, the passing of the 1945 Resolution, and the fight to finish led by Chairman Mao.

The bottom line was what Mao said about the Party—The People Supervise the Party. Xi reportedly added, “It signaled the Party had marched toward maturity in its politics, its ideology, and its organization.”

So, the signal here is for the Standing Committee members and the CCP that as the Secretary General of the party, the president of the country and the head of the Military Commission, Xi Jinping is the New Mao of New China. Like the Biblical adage (all they that take the sword shall perish with the sword), in China, the adage would be ‘all they that kill the Party are killed by the Party’.

Also read: Don’t just ‘keep a watch’ on China’s spy ship at Sri Lankan port. Emulate the enemy

Delhi’s game

On the economic front, China could face problems as the new team, with no known economist to deal with the emerging situation, tries to reconcile manufacturing with a highly restrictive zero-Covid policy. China’s industrial policy spending was far higher than many leading economies, totalling at least 1.73 per cent of GDP in 2019, or over $400 billion in purchasing power terms. It is higher than China’s defence spending in 2019. The slow post-pandemic recovery and the Ukraine conflict have imposed spending cuts on most of China’s client economies except, perhaps, India.

The Galwan clash and the Covid pandemic have forced India to seriously rethink its economic engagements with Beijing. There was a drop of about US$1.5 billion in India’s iron ore exports to China during April-August 2022, US$700 million in cotton exports and a significant drop in some metals, plastics and paper exports. India also levied export duties ranging from 15-45 per cent on iron and steel inputs to ease pressure on domestic manufacturers and stabilise prices, which also had a significant impact on exports.

The advanced economies of the West will sooner or later tweak their independent and collective parameters of engagement with Beijing. The need for a manufacturing centre will arise. New Delhi should recalibrate its economic policies but also keep the powder dry.

The author is the former editor of ‘Organiser’. He tweets @seshadrichari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)