In the realm of geopolitics and warfare, there are many events that defy an explanation; the non-use of the offensive power of the Indian Air Force in the 1962 India-China war debacle is one such oddity. The common acceptance among the public and many security analysts and academicians is that the IAF was not used at all in that disastrous war; nothing could be further from the truth.

The IAF’s transport aircraft fleet and the fledgling helicopter units executed a task that any nation would be proud of; and what adds salt to the feelings of those who participated in that stupendous effort to keep the front-line troops of the Army supplied, and casualties evacuated, is that they have not got their due. As we commemorate what the nation went through 60 years ago, it would only be appropriate to remember those gallant men.

Air Marshal Bharat Kumar, a military historian par excellence, has authored Unknown and Unsung, which chronicles the extraordinary work done by the IAF during that period, especially the critical thirty days beginning 20 October 1962 when the Chinese first struck in the North-East and then in Ladakh.

There were two distinct, and geographically separated, conflict zones. In the Ladakh sector, the terrain was extremely tough and challenging for the Indian Army, with no road connectivity and posts located at altitudes of up to 17,000 feet. In the North-East Frontier Agency (now Arunachal Pradesh) and Assam sectors, though elevations were slightly lower, the region was marked with dense vegetation, unpredictable weather, narrow valleys and no road communications. In both the sectors, the Chinese had the advantage of relatively flat terrain, especially the Tibetan plateau in Ladakh, where trucks and armoured vehicles could easily bring in reinforcements and logistics.

The intentions of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to push its troops to its claim lines became clear in the 1950s. Despite many rounds of talks at the highest levels, and bloody border skirmishes too, the differences came to a head from 1959 onwards when India started establishing posts (beginning with those of the Intelligence Bureau) in areas where only patrolling had been done hitherto; these small 10-12 men locations were not connected by any logistic road infrastructure and were totally dependent for sustenance on supply from the air. The controversial ‘forward policy’ directive came after a high-level meeting in New Delhi on 2 November 1961; the field commanders protested about the ill-preparedness (clothing, equipment and weapons) of their troops and the suicidal positioning of the posts, but were over-ruled. The IAF became their lifeline. For ease of understanding, the Air Force’s remarkable role is hereafter discussed fleet-wise.

Also read: Indian policymakers overread 1962 Chinese threat, could’ve pulled out from the brink

Transport fleet

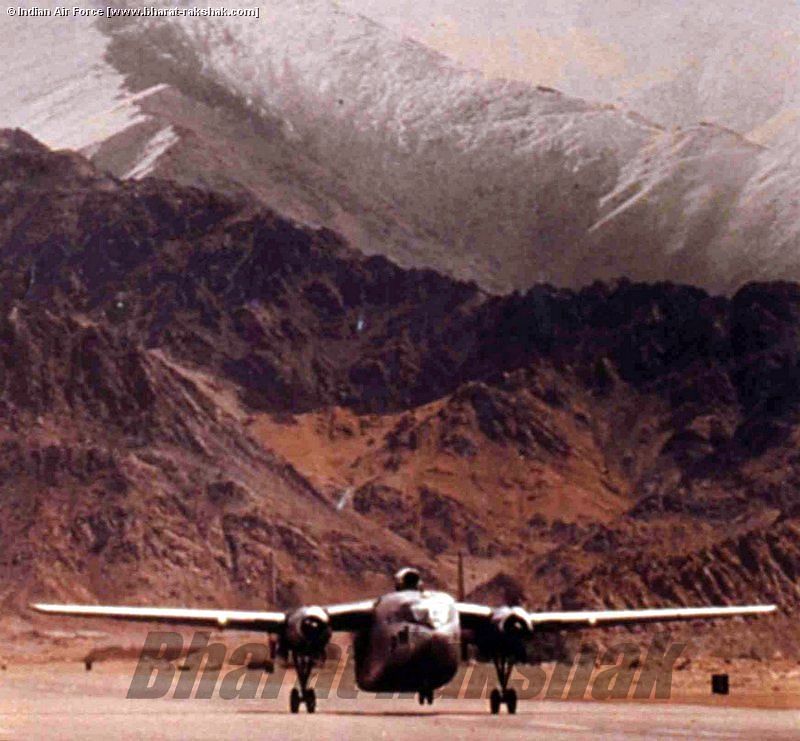

The IAF’s transport fleet consisted of DC-3 Dakota, Ilyushin-14, C-119 Packet, Otter light transport and limited number of An-12 medium lifters; the non-metalled road from Srinagar to Leh had closed due to onset of winter snow and hence the aircraft flew troops, sand bags, barbed wire, food stuff, ammunition et al from Chandigarh, Palam and bases in Punjab to Leh, Chushul, Fukche and Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO) in Ladakh. Scenes of bravery, enterprise and ingenuity were visible at every airbase, and transport crew flew day and night without rest. As the situation at DBO became critical, C-119 Packet aircraft operated to and from the unpaved strip situated at 17,000 feet; and these operations continued even when the Chinese advanced and encircled certain posts. Dropping to these posts continued in plain view of the Chinese and on one particular day, Sqn Ldr Chandan Singh, the captain of a Packet, felt his aircraft getting straddled by ground fire. He continued with the drop and on return to Chandigarh found 19 bullet holes in the fuselage.

Air Force Station Chandigarh was urgently tasked to airlift tanks to Chushul. Chushul airstrip, made of perforated steel planks, is at 14,000 ft and only an airlift of tanks could have neutralised Chinese armour that had broken through. This unheard-of commitment was accepted and when the first 14.5 ton AMX tank was being loaded at Chandigarh, the tail of the An-12 buckled down and the nose of the aircraft lifted up into the sky. A new ramp was created, tyres and logs placed under the tail to support it and then the tank was gingerly driven in. No one was sure whether the aircraft’s centre of gravity was within limits – luckily it was. Six tanks were positioned at Chushul and that stopped the ingress of the Chinese in that area. As Air Chief Marshal PC Lal wrote, “Prior to hostilities, the airstrip at Chushul was used at the leisurely pace of one aircraft a day. During the hostilities it was subjected to six An-12s and about eight packets daily and became unserviceable frequently.”

In the Eastern theatre, Gauhati (which was a civil airfield) became the centre of activity. The Air Officer Commanding Eastern Air Command moved in and operated from a tent next to the flying dispersal. Army demands kept rising and the daily airlift capacity at Gauhati rose from 20-30 tons to 60-70 tons by the beginning of October and to 150-200 tons by the middle of that month. However, on the dropping zones, there was another problem — no spare troops to clear the DZs. Soon, the ridges that served as DZs were saturated.

Students of military history would know that the 1962 war happened in two phases. As Air Marshal Bharat Kumar writes, “In the second phase, small single engine Otters transported more than 2,000 personnel to Walong. In addition, the stocking of arms, ammunition and rations and other stores had to be done simultaneously.” He further adds that “the two units flew 982 hours and airlifted 414 tons of supplies”. The director of Intelligence Bureau, BM Mullik, commenting on this airlift, wrote, “In Walong sector, there was only a small airstrip and the road head was Hayuliang – 40 miles to the southwest. But the Air Force did marvels and flew sorties after sorties and nearly completed the build-up before the second Chinese attack came.”

Also read: Not just Nehru, China’s 1962 war on India also a counter to Mao’s secrets

Helicopter fleet

The small IAF helicopter fleet did yeoman service transporting troops and ammunition right up to the frontlines – and getting shot. Sqn Ldr Vinod Sehgal, Commanding Officer 104 Helicopter Unit, became the first IAF casualty when he flew Major Ram Singh with a wireless set to Tsangdhar on 20 October to re-establish contact with that post. Little did he know that it had been overrun heralding the Chinese invasion. His helicopter, totally intact, was featured in Chinese propaganda photos and films but his name was not in the POW list – he and the Major were killed in cold blood. Sqn Ldr AS Williams, Commanding 105 Helicopter Unit, who went to look for his helicopter was also shot up and had to force land; luckily, he made it back, albeit with bullet injuries. Earlier, on 11 October, Sqn Ldr Williams had evacuated a casualty by night in a Bell helicopter – with the casualty lying behind and shining a torch on his instrument panel for Williams to monitor his critical instruments.

Such were the rescues done, day in and day out, by the brave helicopter pilots before, during and after the ceasefire. When the forward elements of the Army disintegrated and withdrew in an uncontrolled manner (including through Bhutan), helicopters flew non-stop in the hills picking up stragglers by the dozen. In one sortie, Wg Cdr KK Saini evacuated 37 personnel (in peacetime the limit was around 12), including casualties, in a Mi-4 from Walong.

In the Ladakh sector too, the story was similar. Helicopters of 107 Helicopter Unit flew through fire on many occasions to supply troops in the outlying posts, which were overlooked by Chinese picquets, especially in the DBO Sector. And when many posts had to be withdrawn, their casualties were evacuated under extremely trying conditions. In the Galwan sub-sector (the same area that was in news for the bloody clash in 2020) a record of sorts was created when “a whole battalion of 5 Jat was replaced by 1/8 Gurkha, right under Chinese noses” by 107 Helicopter Unit. The Hot Springs and Tsogtsalu area too was looked after through sustenance supplies and casualty evacuations by the Mi-4s.

Technical staff

It is axiomatic that such round-the-clock flying, with repair of battle-damaged aircraft throw-in, would not have been possible without the exceptional dedication of the technical staff. They worked without a break to make sure that sufficient aircraft were available on the frontline. Additionally, there were many instances of incredible recoveries of aircraft which had crashed on the frontlines.

Also read: ‘Great mistake’ or not? Why India decided against deploying Air Force in 1962 war with China

Fighter fleet

The fighter fleet was ready and raring to go. The IAF had Vampires, Toofanis, Mysteres and the newly inducted Hunters as the strike elements. The Canberra was the medium range bomber that also had a reconnaissance version. Extensive surveillance was done by the Canberras as events started hotting-up, as well as during the conflict. As Air Vice Marshal Arjan Singh revealed after the war, “It was planned that the Canberra would attack Chinese airfields by day while the Mystere and Hunters would be used for interdiction.” This author spoke to Air Chief Marshal AY Tipnis, who was a Fg Offr then. He said: “We were at cockpit readiness in Ambala. I was No 2 to my CO, strapped up awaiting orders to get airborne. The Hunters were armed with T-10 rockets and front gun ammo and our targets were tanks in the Chushul area. We spent an hour strapped up, with the Station Commander on the telephone to Air Hq, after which we were asked to stand down.”

Similarly, the positioning of squadrons indicated that the IAF was ready with its plans to strike. As Bharat Kumar has written, “Toofani and Vampire aircraft deployed in the east would have been used for interdiction and close air support. Gnats and Hunters …(for) air defence tasks as was evident from the orders given to various units for this purpose. Vampire night fighters were to look after the air defence of Delhi and Leh at night.” Airfields at Srinagar, Adampur Ambala. Halwara, Palam and Agra had fighter squadrons ready to go into action to look after Ladakh. Kalaikunda, Bagdogra, Tezpur and Chabua airfields were poised in the Eastern sector.

Why didn’t the orders come? While many reasons have been given by different people, four stand out. First, a fear that if the IAF was used, the Chinese Air Force would enter the conflict and bomb Indian cities since our air defence structure was weak. Second, even if orders were given to the IAF to attack, Indian aircraft could not reach Chinese cities which lay far beyond Tibet. Third, an assessment that close air support in the East would not be effective due to the thick vegetation that prevailed there. Fourth, if the conflict expanded due to the entry of the IAF, support in terms of US fighter aircraft (manned by American crew) to protect Indian cities would not be available.

In hindsight, this logic is incomprehensible. IAF headquarters would have known that the only Chinese bomber that could have reached Calcutta or Delhi was the piston engine IL-28. The Chinese aircraft would have been severely handicapped in their flying ranges and ammunition carrying capability by the high altitudes of their airfields in Tibet, which were very few in any case. IAF’s fighter interceptors were positioned on our airfields in the plains to take them on.

The issue, however, appears to be that the political leadership was not willing to accept any threat to the cities. Why? Because there was panic in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Madras (now Chennai) when the Japanese managed some bombing missions there in World War 2. This raises the question as to whether it was worth taking this risk as against not committing one’s potent offensive arm to stop the national humiliation that was ongoing. For the political leadership, this would have been an important point to consider, but it was India that was at war, and that includes the civil populace too. So, this is one ‘if’ that begs an answer, if ever there is one.

Were the chiefs of the armed forces so inconsequential in the higher defence management structure that they could not thump the table and convince the political leadership? Paradoxically, there are writings to the effect that Army and Air Headquarters themselves were not forceful enough to push this decision, and in a way were equally blameworthy.

To put it bluntly, we had a card up our sleeves that was wasted. To add the proverbial salt to the wounds, a Pentagon study carried out immediately after the ceasefire concluded that if India had used air power, “It would have made a significant difference to the war’s outcome.”

Postscript: I spoke to Air Marshal Trevor Osman, who was a young Flying Officer in Tezpur during the war. He said, “The helicopter pilots were overworked and tired with sleep deprivation. We, young fighter pilots, flew as their co-pilots and were handed over controls of the helicopter after take-off, while they grabbed some sleep, till just before landing when they were woken up to touch down.” Air Mshl Bharat Kumar, in his book, has a similar story to narrate, about he being handed over controls of a Dakota after take-off while the overworked pilots went to sleep till before landing.

That’s how involved the rank and file of the IAF was during that fateful 1962 war. One hopes that the young of today, both in uniform and on the civil streets, study the happenings of that fateful period so that India does not ever get a black on its proud history.

The author is a retired Air Vice Marshal who delves into matters of national security and air power issues. He tweets @BahadurManmohan. Views are personal.

This article is part of the Remembering 1962 series on the India-China war. You can read all the articles here.

(Edited by Prashant)