The Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance, armed with its electoral catchphrase, “Jungle Raj ka Yuvraj”, hit the opposition led by Tejashwi Yadav where it hurts the most. The Bihar election results hint that the narratives of the ‘Jungle Raj’ succeeded in forcing people to recall the politics and governance that ended 15 years ago and which, according to the detractors, carried crime in its DNA. The NDA’s poll strategies may have ensured Nitish Kumar’s return by evoking the ghost of the Jungle Raj, but crime data tells a different story.

A simple analysis of the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) annual data on cognisable IPC crimes in major Hindi-belt states shows that, in the last 45 years, crime count was lowest in Bihar.

But since the 1990s, Bihar has been reduced to dark narratives and pejoratives such as BIMARU and Jungle Raj – the second one being the most damaging for the state’s development.

Bihar’s journey to Jungle Raj

The entire Jungle Raj narrative emanates from imaginations of poor law and order situation and high crime rates in the 1990s. The narrative, largely built and reinvented around sensational crime stories with graphic details in media, stocks of anecdotes, and electoral political narratives, turned Bihar into a dreaded place in people’s imaginations. It made such a deep impact on the psyche that even Biharis living in other states would avoid visiting their hometowns or villages, forget about outsiders.

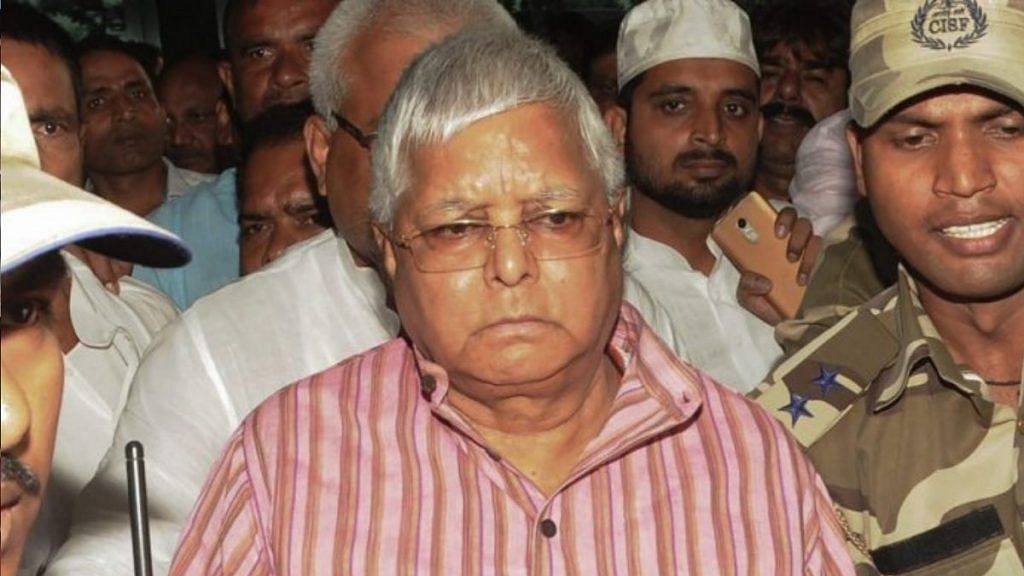

The narrative, however, is rejected by scholars such as Christophe Jaffrelot who refers to the period as a regime of social justice. It is said that with the advent of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s government in Bihar, the established political power hierarchies (well aligned with caste hierarchies) faced stiff challenges. The oppressed castes and minorities found a voice and raised it to a level uncomforting to certain sections of society holding key positions in each of the four pillars of democracy.

While as chief minister, Lalu Prasad, and a few of his kin and close aides, were found to be involved in crimes of varying degrees of intensity, it was, however, used as a peg to hang the entire government and administration. The Jungle Raj narrative, which had started around the criminal acts of ruling politicians, was solidified with the incrimination of Lalu Prasad in corruption cases. While the incidence of any crime is unjustifiable, it seems that the issue of crime in Bihar has been magnified with the lens of the Jungle Raj narrative. Lalu Prasad Yadav and the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) governments were held disproportionately more accountable for the same issues than any other ruling government in other states.

Also read: Tejashwi’s arrival, Nitish’s tenacity, Shah’s masterstroke — 5 takeaways from Bihar results

Crimes, facts, and fiction – what data tells

The NCRB data on cognisable IPC crimes for the last 45 years shows that crime counts (both in terms of absolute figures and in proportion to the population, as seen in Figures 1 and 2) was the lowest in Bihar among all Hindi-belt states. The analyses certainly include RJD’s ‘misrule’ phase, on which the entire Jungle Raj narrative had been premised. Even in comparison to Gujarat (taken as ideal in terms of investment climate, post-reform economic growth, and development), Bihar performed better and consistently registered lower crime counts.

Bihar’s position in interstate crime statistics is counterintuitive and does not add up to the Jungle Raj stories. It, nevertheless, does not absolve the RJD from the popular opinion that it was the worst in terms of law and order and witnessed huge spikes in crime with every passing year.

A close look at data (crimes per 100,000 population), however, clears the air and gives us a diametrically opposite understanding (Figures 3 and 4). It shows that the phase of so-called misrule and Jungle Raj (1990-95) was, in fact, marked with the lowest crime rates in the last 45 years in Bihar. Moreover, a significant dip in crimes can be seen during the RJD’s rule in comparison to the preceding 15 years, whereas a sharp consistent rise in the same is seen with the arrival of the Janata Dal (United) or JD(U).

The biggest irony is that the quinquennial crime growth rate – that is, the rate every five years – registered a fall of -18.32 per cent in the first term of Lalu Prasad (a perceived culprit in Bihar’s history) as against a rise of 17.34 per cent during the first term of Nitish Kumar (known for sushasan and development), which further went up to 33.25 per cent in his second term.

Also read: Modi brings up ‘Jungle Raj’ as BJP and JD(U) fall back on old line of attack on RJD

Economic impacts of the Jungle Raj story

The contradictions between data and Jungle Raj narratives are stark and seem to have served their political purpose well. However, they have been remarkably damaging for Bihar and its people.

While the JD(U)-led governments failed to make any significant change, Nitish Kumar could also barely dispel the spectres of the Jungle Raj. This along with other structural variables in effect kept innovators, investors, industrialists, and capital away from the state and subdued Nitish Kumar’s development agenda. A review of the FDI (foreign direct investment) inflows in Bihar gives important insights on the issue (Figure 5). While FDIs depend on a host of factors, they are very sensitive to the prevalent socio-political environment at investment locations. Bihar received only a paltry amount as FDI when other Hindi-belt states (even with higher crime rates) kept receiving investments in varying amounts in the post-reform period.

In a transforming post-reform Indian economy, the market forces were expected to play a significant role in economic growth and generation of employment and other positive externalities. Bihar, however, overcast by the Jungle Raj story, failed to exude any positive vibes for market forces and therefore missed out on opportunities. It failed to attract investments, witnessed dismal levels of job creation, per capita production, and income. This led to economic inertia and caused a significant increase in the rate of out-migration from Bihar (Figure 6).

In a period of two decades (1991-2011), Bihar’s net-migration rate has doubled. In only the last decade, more than 30 lakh people migrated from Bihar, which consisted primarily of the young population, also known as ‘demographic dividend’ in development debates.

In the post-reform period, when many states were making development strides, Bihar largely remained in a unique fix. Its complex political metamorphosis in the ’90s trapped it into something called ‘simultaneity’ in statistics (wherein X causes Y, and Y in return causes X, and so on). The narratives manufactured to replace the RJD-led ‘social transformation regime’ with a ‘pro-development political regime’ did irreparable damages to the image of the state. They turned Bihar into a no-no for market forces and development agents. And the JD(U), after its failures on sushasan and development agenda, kept refreshing and reinstating the Jungle Raj narrative for electoral gains. So, any positive sentiment and interest towards the state, germinating on the time-healed public memory, were diffused and Bihar remained stuck in the unique fix between Jungle Raj and underdevelopment.

Also read: Despite the sweet victory, Modi-Shah BJP has a Nitish Kumar-sized problem in Bihar

Time to get over Jungle Raj

For long, we have been witnessing Bihar and its people stuck under imposed identities. While the people seem desperate to shake off manufactured narratives from the past and make a fresh start, a large section of the state’s political leadership keeps harping on the past. However, as seen in the 2020 election campaigns, people want to hear about their real concerns – education, health, unemployment, development, and migration. So, this may be the best time to mainstream people’s questions in political narratives. If Bihar succeeds, it could be the beginning of a paradigm shift.

The author is Assistant Professor, Centre for Health Policy, Planning and Management, Tata Institute of Social Science. Views are personal.