Facing the grim stare of a judge in the bowels of a government office in the flyblown town of Dera Ismail Khan, the actress Musarrat Shaheen prepared for the most important performance of her life. The star of hundreds of low-budget Pashto films—among them the wilfully-misspelt 1990 cult classic Haseena Atim Bum—Shaheen had devoted her later life to contesting elections against the fundamentalist politician Maulana Fazlur Rehman. Now, her war against clerical hypocrisy depended on her delivery.

The cleric’s supporters had turned to a then-obscure clause in Pakistan’s constitution, mandating that candidates in elections prove their credentials as pious Muslim, sadiq (truthful) and ameen (faithful). The judge demanded that she demonstrate her knowledge of Islam.

Flawlessly, Musarrat delivered the Sura Akhlas and the Dua-e-Qanoot and then offered to recite any other passages of the Quran the judge might wish to hear. Then, she majestically swept out onto the streets of National Assembly Constituency 124.

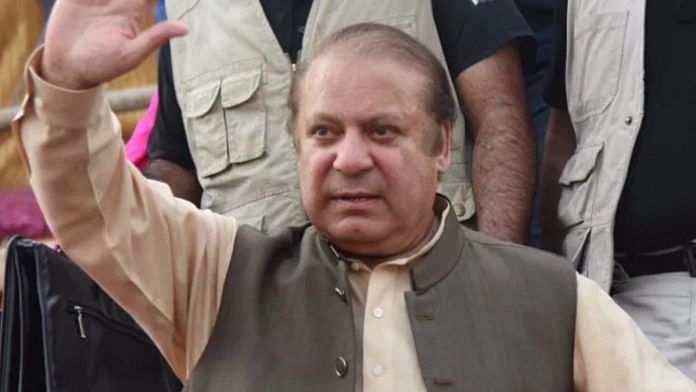

Nawaz’s sadiq and ameen problem

This week, ahead of elections scheduled for 6 November, former Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif announced that his brother, ex-PM Nawaz Sharif—the most high-profile victim of sadiq and ameen requirement of Article 62 (1)(f) of Pakistan’s constitution—would return from self-exile in London next month. The Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) desperately needs its star politician to shore up its popularity, which has been hard hit by economic distress and soaring energy prices.

Later this month, Sharif’s bête noire, Pakistan Supreme Court Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial, author of the 2018 judgment that disqualified Nawaz from membership of parliament for life, will retire from office. Nawaz and other PML-N leaders hope the new chief justice will prove willing to reverse that order, either by amending the length of disqualification or clearing him of corruption-linked allegations.

There is no way of telling how the courts will deal with the issue, but the requirement of piety goes to the heart of Pakistan’s dysfunctions. The use of Islam to legitimise the power of military and civilian elites wounded the country’s democracy, perhaps beyond healing.

Even though the PML-N is eager to help Nawaz escape disqualification, it is showing little interest in addressing the larger problem, and its own complicity in creating it. Indeed, lawmakers are doubling down on brutal blasphemy laws in a bid to seize the religious high ground from increasingly powerful jihadists.

Also read: Imran Khan’s prosecution won’t do much. The military is at the heart of Pakistan’s corruption

The Islamic State and democracy

Ever since its Independence, Pakistan grappled with the role Islam ought to have in its constitution and laws. Even though the constitutions of 1956 and 1962 conceded sovereignty law with god, not the people, the practical impact of this principle was limited. The eligibility of lawmakers rested on questions like citizenship, mental health and financial solvency, not piety. PM Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s 1973 constitution advanced the Islamisation project, but again in ideological terms.

The nuts-and-bolts changes to the electoral qualifications law began under the military regime of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, lawyer Saad Rasool has recorded in a thoroughgoing analysis. In 1985, new clauses were inserted, demanding members of parliament be of “good character,” have “knowledge of Islamic teachings,” and, of course, meet the benchmarks of sadiq and ameen.

Zia’s election laws were part of a larger set of Islam-inspired legislation, including the setting up of shari’a courts, the imposition of religious taxes, and even the rules of evidence. The laws, political scientist Vali Nasr has noted, gave substance to the Right-wing Jamaat-e-Islami’s promise “to attain a utopian Islamic state that would embody and implement the core values of Islam, and thus solve sociopolitical problems.”

Law scholar Amber Darr has pointed out that post-Zia governments continued these efforts. Former interim PM Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi’s government enabled the payment of blood money. The governments of Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz enforced religious laws in Pakistan’s north-western tribal areas and expanded the scope of blasphemy laws.

Even though another military dictator, General Pervez Musharraf, would seek to expand these requirements further, the courts pushed back. The requirements of piety had little practical impact on Pakistani politics or politicians.

However, from 2009, former chief justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry began using the disqualification clauses of Articles 62 and 63 to remove lawmakers accused of having obtained fake degrees, concealing assets, and hiding dual nationalities. Even though his successor, Chief Justice Asif Khosa, described the terms sadiq and ameen as “obscure and impracticable,” his colleagues largely disagreed.

The 2013 general elections saw returning officers engage in the policing of candidates—especially women. Tayyaba Sohail Cheema, a candidate in Lahore, was ordered to display her face to the public on the grounds that the provincial election commissioner did not believe she looked her stated age. Another candidate, Sadia Sohail, was hectored about purported conflicts between her duties as a mother and politician, journalists Khalid Qayyum and Rana Yasif reported.

Karachi politician Zahid Ahmad, a leader of the far-Right Sunni Tehreek, was asked by Judge Farzana Iqbal what the abbreviation L.L.B. stood for, and how to spell ‘graduation’ and ‘superintendent’. He failed all three questions. The journalist Ayaz Amir—who without doubt would have passed the same tests—was disqualified for his political writing.

Faced with the disqualification of Nawaz for charges related to overseas bank accounts and properties, the government considered amending the constitution—but it was too late. The former PM would be arrested and then allowed to leave Pakistan for treatment of medical conditions. He never returned.

Also read: Power game in Pakistan remains unfinished. Imran’s arrest shows army playing with a weak hand

The long coup

The fate of Nawaz was linked to the wider ascendancy of the military, which cast itself as a morally superior alternative to corrupt politicians. Even the pretence of accepting subordination to the civilian government, the political scientist Aqil Shah has noted, had disappeared by 2015. Following the 2014 massacre of 132 school students by Tehreek-e-Taliban terrorists at the Army Public School in Peshawar, the military arrogated the right to prosecute the alleged perpetrators in secret courts.

Imran Khan’s rise as PM brought to power a politician who claimed to embody the moral values the military represented. Like his predecessors, though, Imran’s anti-corruption credentials would be called into question as the military became concerned with his growing power.

As Nawaz prepares to return home, Pakistani democracy is degenerating into a kind of de-facto military rule. The Pakistan Army’s chief, General Asim Munir, is engaged in polemical extravagance normally associated with politicians. At one recent meeting with business leaders in Karachi, he promised to bring in $100 billion in foreign investments, twice as much as the country drew in all the years from 1970 to 2022.

Even if Nawaz succeeds in having himself declared both sadiq and ameen, and Imran replaces him in military demonology, he will, at best, inherit a half-formed democracy. Like the incredibly courageous Mussarat, politicians like Nawaz need to summon the resolve to challenge military authority, and the religious fundamentalism that sustains its power.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)