Narsinhbhai Patel’s life is a fascinating account of a social reformer ahead of his time, an early advocate of women’s rights, and a staunch atheist with a phenomenal Gujarati book on atheism to his credit. The Criminal Investigation Department of the erstwhile Bombay Presidency considered him the most dangerous man in the headstrong Patidar community.

Patel started as a revolutionary and a follower of the bomb cult of Bengal. Indian philosopher Aurobindo Ghosh and his more radical brother Barindra Kumar Ghosh were inspirations for him during his college days at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. After graduation, Patel took a job as a school teacher in Baroda State. He was posted at Mehsana in Gujarat, where he started a printing press and published a monthly Shikshak (The Teacher).

He also wrote, translated, and compiled books on European revolutionaries like James A. Garfield, Giuseppe Garibaldi, and Giuseppe Mazzini in Gujarati. His most notorious book was a DIY guide on making bombs, innocuously named Vanaspatini Davao (Herbal Medicines). It was a translation of Barindra Ghosh’s Mukti Kon Pathe (which way to liberation). Patel’s publications earned him the wrath of the British government.

Also read: Remembering Shaheed Udham Singh, the revolutionary who avenged Jallianwala Bagh

Revolutionary at heart

The British banned the book of bomb-making and started hounding Patel. He was jailed for a brief period in 1912. Gaekwad state also banished Patel for five years and imposed a fine of Rs 300. His inability to pay the fine would add an additional year of exile. Patel went to Pondicherry, a French colony at that time, but the British followed him and pressurised his employer there. Patel left for Africa to escape the heat.

He went to Mombasa, East Africa, and stayed for a longer period at Mwanza, a German colony. He learned German there. His wife and two daughters joined him in Africa. After the British captured Mwanza in the First World War, Patel shifted his base to Jinja in present-day Uganda. The stay in Africa provided ample time and opportunity for Patel to read and think. Going through Leo Tolstoy’s A Murderer’s Remorse changed his views drastically and converted him to a practitioner of non-violence. He came in contact with CF Andrews who was a Christian missionary and a friend of MK Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore. He suggested Patel join Shantiniketan ashram after returning to India.

Following Andrews’ advice, Patel went to Shantiniketan and taught German there. He stayed for approximately three years (1920-1923) with his family and the luminaries of Shantiniketan. A revolutionary at heart, Patel was never shy of speaking his mind to anyone—not even to Tagore or Gandhi whom he held in high regard. He confronted Tagore during one of the informal night gatherings when Tagore was praising the Japanese and their sense of art. “Who has enslaved Korea and inflicted atrocities on the Koreans?” Patel asked point blank. When Tagore tried to present the Japanese side and said that they were popular among Koreans, Patel retorted, “By that standard Nero playing fiddle from his terrace while Rome burnt must be popular as well.” Tagore, unlike some of his disciples, took Patel’s comments in stride and appreciated him for speaking his mind.

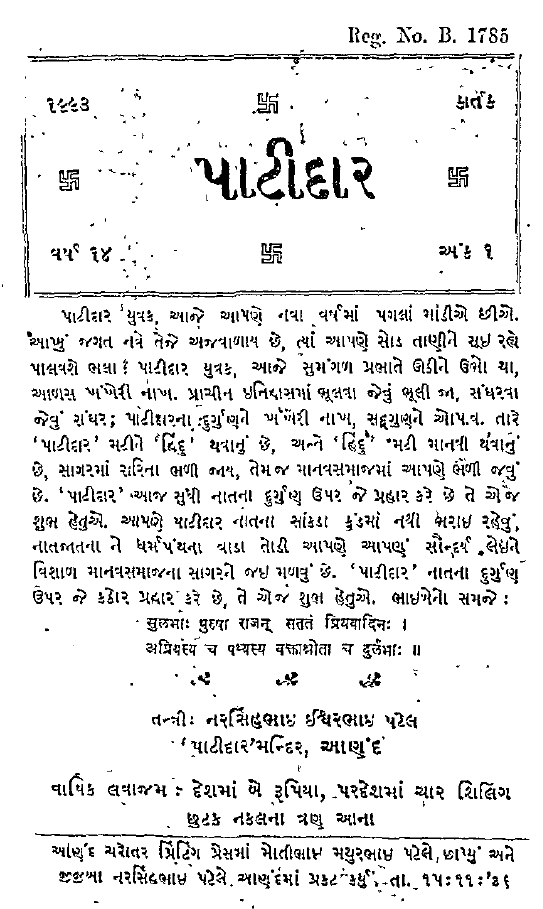

After leaving Shantiniketan, Patel settled in Anand, a town in the Charotar region in central Gujarat later known as the milk capital of India. It was near his native village Sojitra. Appalled by the social ills of his community, Patel started a monthly named Patidar in 1924. The magazine aspired to reform the evil practices within the caste group, lead fellow Patidars to break the shackles of caste-creed. His writing style was direct, hard-hitting, and fearless.

He took an active part in India’s freedom movement, received Gandhi at Anand during the famous Dandi March, and served jail terms. But when Gandhi scolded his wife Kasturba for going to Jagannath temple in Puri, where Dalits were not allowed, Patel wrote in Patidar that it is not the business of Gandhi to decide what his wife should do and where she should go. He remarked that even a Mahatma like Gandhi is not completely free from the age-old practices of patriarchy.

Also read: Batukeshwar Dutt — India’s revolutionary forgotten under shadow of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru

Denying God

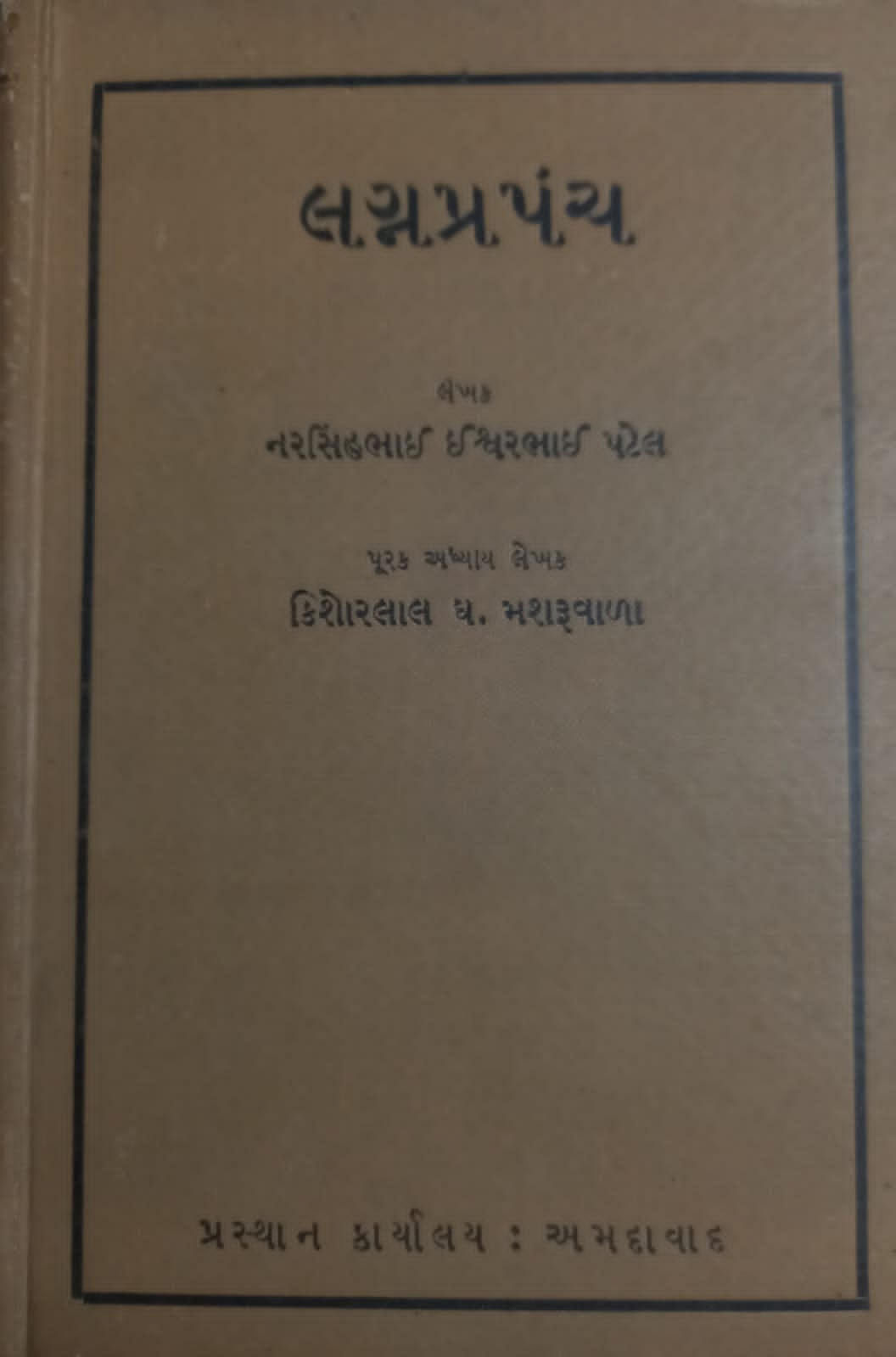

His book with an acerbic title Lagnaprapanch (the fraud of marriage) in 1937 earned him the identity as the best advocate of women. The preface of this 650-pager was written by Gandhi’s close associate and thinker Kishorelal Mashruwala. Patel’s central argument in the book was that the institution of marriage was created to suffocate and crush women. His 1932 book Ishwarno Inkaar (denying God) was equally radical. The seeds of atheism were sown in Patel’s mind very early. Born in a family of Swaminarayan followers, Patel was impressed by some of the tenets of Arya Samaj. But he could not accept that the Vedas directly came from God.

Though his home in Anand was named Patidar Mandir, Patel appealed to the readers—especially the youngsters—in Ishwarno Inkaar to read, think and brush the religions away. He had no hesitation in saying that even if he is the only one to believe in his thoughts, he would not hesitate in proclaiming what he finds as truth. Gandhi read some of Patel’s books during his imprisonment with interest, especially Africana Patro (Letters from Africa), and praised his candidness and frankness.

The demise of his wife Diwaliben and an attack of paralysis broke Patel’s body but his spirit was intact. When former prime minister Morarji Desai asked him in the last phase of his life if he would ultimately believe in God, he did not yield. His daughters Shantaben and Vimlaben were active in carrying his legacy during his imprisonment and illness. They took the reins of Patidar and proved to be worthy daughters of an illustrious father. His son Ramanbhai was in Africa from a young age, but Ramanbhai’s son Shantibhai joined his grandfather and took part in the freedom movement.

Narsinhbhai Patel did not live to see the country attain Independence. But he was a perfect example of what a citizen of an independent, democratic country should be like.

Urvish Kothari is a senior columnist and writer based in Ahmedabad. Views are personal. This article is part of a on-going series, Gujarat Giants.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)