In December 2018, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lost three key elections in India’s Hindi belt, in the states of Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh (MP) and Rajasthan. Owing to frustrations over economic distress, particularly in rural areas, the BJP’s appeal had started to unravel, leading to shocking defeats in state elections. In two of these states, Chhattisgarh and MP, the BJP had ruled for over a decade under the charismatic leadership of Raman Singh and Shivraj Singh Chouhan, respectively. Going by historical trends, these election results seemed to be a harbinger of things to come for the BJP in the upcoming 2019 national election (Verniers 2019).

Yet, in the 2019 national election, not only did the BJP reverse the trend, it essentially replicated (if not bettered) the electoral sweep of the 2014 national election. In Chhattisgarh, MP, and Rajasthan, the BJP won 61 out of 65 seats for a strike rate of 94% (in 2014, it had won 62 out of these 65 seats). At the time, some observers of Indian politics attributed the BJP sweep, a reversal of a trend seen months earlier, to proximate causes—namely a purported military strike in Balakot, Pakistan.

But state elections subsequent to the national elections showed the same pattern. In Haryana, Jharkhand, Delhi, the BJP won 29 out of 31 seats (94% strike rate)1 in the 2019 national election, tallying more than 50% vote share in each state. However, BJP’s vote share dropped 18 percentage points or more in the state election in each of these states—all of which took place within one year of the national election. We now understand that this disjuncture between state and national election results for the BJP were not due to a momentary surge of nationalism but rather a larger structural shift in Indian electoral politics.

In this essay, I wish to offer conjectures on two questions. First, why have the BJP’s electoral fortunes in national and state elections diverged so significantly, and will this pattern continue to persist in future elections? Second, what might this pattern signal for politics within the BJP?

In order to grapple with these questions, I assess the electoral impacts at the state level of political and economic centralisation around Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In other work, I have argued that centralisation of economic benefits under Modi has weakened the electoral position of regional parties in national elections (Aiyar and Sircar 2020). Here, I look at the other side of the electoral arena—state elections.

I argue that this extraordinary centralisation of power, not just institutionally but also within the BJP, implies that the voter is increasingly likely to “attribute” (that is, give credit for) the delivery of economic benefits to Modi rather than the state-level leader. This contrasts with much of the 2000s, where, after a spate of fiscal decentralisation, a number of state-level leaders built their reputations on the ability to deliver benefits. Many of these leaders, like the aforementioned Raman Singh and Shivraj Singh Chouhan, were BJP leaders, and others, like Nitish Kumar in Bihar, were allied with the BJP.

This has affected state elections in three important ways. First, as economic delivery is increasingly attributed to Modi, many state-level leaders have lost their core public appeal. Second, although not necessarily maximizing electoral returns at the state level, this pattern of economic centralisation and attribution to the center empowers Modi and his coterie to centralise power within the BJP—as it adversely impacts the independent bases of support for strong regional leaders with the BJP. Third, with the attribution of economic delivery being centralised, regional leaders must increasingly distinguish themselves along dimensions other than economic welfare. For the time being, these incentives may benefit existing regional leaders, who often have formidable support bases in caste, linguistic, and identity-based terms.

Also read: India wants US-style govt system, but forgets America doesn’t have ‘one nation, one election’

Differences between state and national elections

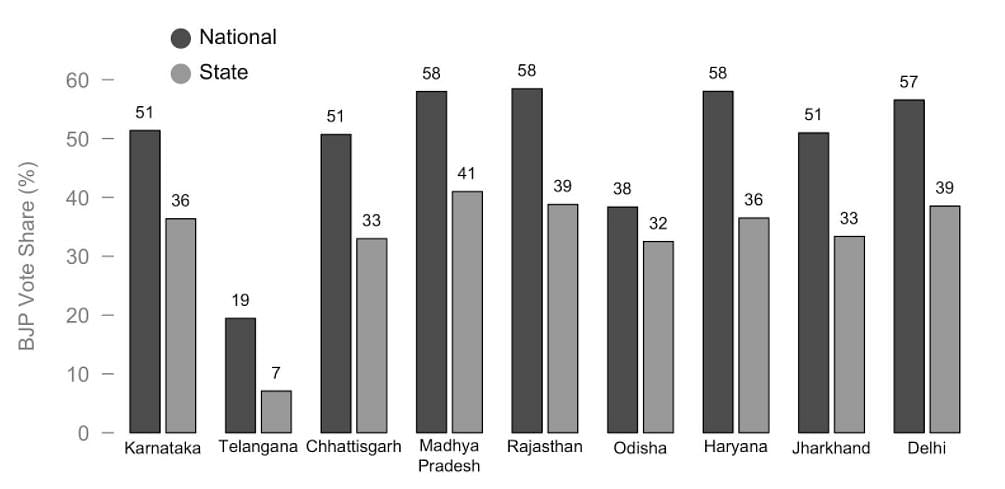

Recent state elections have shown a significant drop in vote share for the BJP as compared to its performance in the 2019 national election. Figure 1 compares the BJP’s vote share in the 2019 national election to the BJP’s vote share in recent state elections. In order to keep the comparison simple, Figure 1 compares states that went to the polls from December 2017 onward in which the BJP received significant vote share and was not a part of a major pre-electoral coalition—excluding smaller states in the North East. This is not to dismiss these other states, but only a recognition that the dynamics therein are different than the broader trends in the rest of the country.

With the exception of Odisha and Telangana, the gap in vote share between state and national elections is at least 15 percentage points. Telangana is a state in which the BJP was not highly competitive in either the state or national elections, and the Odisha election was a simultaneous election in which one may expect greater concordance between state and national electoral results. Even in Odisha, the five percentage point gap suggested a significant amount of “split ticket voting” in the population (Aiyar and Sircar 2020).

Most importantly, these states show wide variation in the BJP’s role in regional politics, from strongholds like Gujarat to states with established charismatic BJP chief ministers like MP and Chhattisgarh to states in which BJP’s chief ministerial face does not independently command his own base like Haryana or Jharkhand. This suggests that the electoral gap is a national phenomenon and not driven solely by regional factors.

Also read: Saving India needs saving Indian federalism

Centralising attribution

To unpack this phenomenon, let us start by chronicling the centralisation in welfare delivery that has occurred since Modi came to power in 2014 (Aiyar and Tillin 2020). The goal of this process was to create a direct connection between the voter and Modi through welfare benefits. It has been documented that after a political jibe in 2015 by rival Rahul Gandhi that Modi was running a suit boot ki sarkar (a government benefiting the rich), Modi went about refashioning himself as a garibon ka neta (a leader of the poor) (Jha 2017: 18). In this process, the government branded a number of welfare schemes that directly promoted Modi’s visage, for example, the Ujjwala scheme promising free liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) cylinders or Jan Dhan Yojana to promote greater banking access in the population. This is similar to a political strategy used by former prime minister Indira Gandhi, at a time with great regional factionalism, to build a direct connection between the voter and prime minister and circumvent the welfarist connection between voters and regional leaders (Wilkinson 2007: 116).

While there is no clear evidence the schemes under Modi have been more effective, there is little question that the BJP engaged its impressive party machinery in advertising these schemes and building the perception that Modi directly delivered benefits to the voter (Aiyar 2019). As I have argued elsewhere, this method of political campaigning is core to the politics of vishwas (trust/belief). In this model of politics, the party machine is directly engaged in building a visceral link between leader and voter and dictating the issues upon which political support is to be based (Sircar 2020). This is a direct reversal of an accountability-based model in which voters have a priori ideological or issue-based dispositions upon which they assess political leaders. The upshot of this process is the strong political attribution of the delivery of welfare benefits to Modi, not the regional leader, and that this attribution need not be grounded in empirical realities.

To understand why this might affect election outcomes, we need a “model” of how voters make decisions. For simplicity, we assume that the voter is choosing between the BJP and one other party (that is, there are two feasible choices). This is a standard assumption in understanding voting behaviour in “first past the post” electoral systems like that of India (Cox 1997). Voters assess the weight of the evidence along multiple axes, which can include economic delivery, caste/religious associations, social issues, and foreign policy — although, as discussed above, “the evidence” can be manufactured or perceived and not necessarily empirically accurate. Using this evidence, voters choose the candidate/party/leader that is most likely to serve their interests in the future, what political scientists call “prospective voting” (Lockerbie 1992).

If certain regional leaders have built their reputation on economic delivery, and greater attribution is now being given to Modi on this front, then these regional leaders should lose electoral ground to their chief competitors — who may appeal to voters along other dimensions. We thus expect that chief ministers from the BJP and those allied with the BJP, like Shivraj Singh Chouhan (MP), Raman Singh (Chhattisgarh), and Nitish Kumar (Bihar) who have built their reputations as “welfarists,” to be the most adversely impacted by the centralisation around Modi. Beyond adversely impacting their electoral chances, a number of welfarist BJP chief ministers are those who have or had been ruling chief ministers for many years, plausibly being re-elected due to their economic performance (Vaishav 2015). This means that the centralisation of political attribution for welfare benefits is most likely to weaken the position of the longest serving and most reputable regional leaders within and aligned to the BJP.

One may naturally ask why the same phenomenon should not hold for those regional leaders unaligned with the BJP. One simple answer lies in the fact that the BJP machinery is more trained to advertise the work of the Prime Minister and less of individual chief ministers. A more sophisticated plausible answer lies in the relative appeal of leaders representing other parties. Many regional parties like the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) in Bihar or Janata Dal (Secular) (JD[S]) explicitly appeal in identity-based terms to particular caste groups beyond any appeal in welfarism. But even the Congress, the BJP’s chief competitor in many states, has a history of being a “catch-all” party that has stitched together multiple caste, religious and class identities (Heath and Yadav 1999; Chandra 2000).

This is very different than a BJP that has traditionally been associated with upper caste Hindus and has built a larger support base through Hindu polarisation and broad-based appeals. The implication is that as the political attribution for welfare benefits is given to the center, the identity-based linkages of BJP’s regional competitors become more salient in determining state-level electoral outcomes. It is worth pointing out here that the one regional BJP leader whose clout has noticeably grown in the Modi era is Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath, whose appeal based on his Thakur identity, Hindu mobilisation and aggressive policing, not welfarism (India Today-Karvy Insights 2020).

Also read: BJP’s undiluted power at the Centre has weakened the bargaining position of regional parties

A look at Madhya Pradesh

The state of MP provides an interesting case study for the argument I have made above. In 2005, BJP’s Shivraj Singh Chouhan became the chief minister after crafting a campaign around the welfarist demands of bijli, sadak, pani (electricity, roads and water). He would rule MP until his ouster in 2018 (and come back to power in 2020 after Kamal Nath’s Congress government fell due to Jyotiraditya Scindia’s exit from the party). In the 2008 and 2013 state elections, the BJP won 143 and 165 seats (out of a total of 230), respectively, easily forming the government.

The 2018 state election was the first election in the Modi era, and the vote share of the BJP’s seat share would tumble to 109 seats on 41% vote share, with Shivraj Singh Chouhan and the BJP losing control of government.2 But less than six months later, in the 2019 national election, the BJP would secure 58% of the vote in MP—a 17 percentage point increase in vote share. The state of MP merits closer inspection, as it is a state that had a highly popular, and long serving, welfarist chief minister from the BJP who suffered a significant decline in popularity, with a significant gap in state and national electoral results for the BJP.

There is some circumstantial evidence for the popularity of Prime Minister Modi’s schemes vis-а-vis those of Shivraj Singh Chouhan. In the 2018 Madhya Pradesh state election, post poll conducted by Lokniti (2018) surveying over 5,800 people, 92% of respondents reported having heard of the Ujjwala scheme, with 55% having directly benefited from it. Both percentages of those having heard and benefitted are higher than the corresponding percentages for any of the 10 state-level schemes asked about in the post poll. In general, the survey results report significantly higher percentages of voters having benefited from schemes associated with Modi as compared to those associated with Shivraj Singh Chouhan. This is somewhat surprising given Shivraj Singh Chouhan’s long tenure and reputation as a welfarist chief minister.

We can also frame a more direct test. In the wake of India’s 2016 demonetisation exercise, serious economic distress was reported in rural MP (Sircar and Kishore 2019). In the aftermath, Shivraj Singh Chouhan’s government announced the Bhavantar Bhugtan Yojana (price difference payment scheme) in which the government would pay the difference between the selling price of any crops and the minimum support price (MSP). This was effectively a large subsidy to rural MP. In February 2019, as India was getting ready to go to polls for the national election, Modi announced the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (Prime Minister’s Farmer Tribute Fund) in which all small and marginal farmers in the country would receive income support of Rs 6,000 per annum.

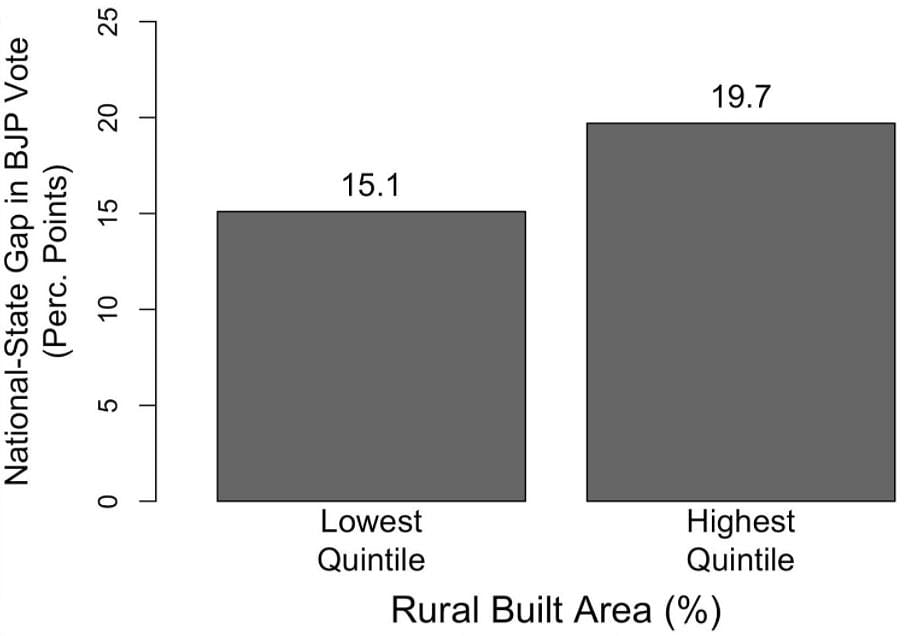

These different welfarist policies at the state and national levels frame a natural empirical test. We wish to see whether the gap between national and state vote share for the BJP is greater or narrower in the most rural areas. A greater gap would suggest greater appeal of Modi’s policy and a narrower gap would suggest the opposite. Because rural classification in the Indian Census 2011 data is both out of date and subject to administrative peculiarities, I use satellite maps provided by the European Space Agency to calculate the percentage of land in an assembly constituency that can be classified as “rural” in terms of its built area.3

Figure 2 shows the average assembly constituency-wise differences (in percentage points) between the 2019 national and 2018 state election in MP for those constituencies with the least rural land in percentage terms (lowest quintile) and those with the greatest amount of rural land (highest quintile). As can be observed, the most rural areas display a national-state gap that is 5 percentage points higher than the least rural areas. This lends credence to the idea that Modi’s welfarist policies generated greater appeal among voters than those of Shivraj Singh Chouhan.

Also read: How BJP’s one-party dominance differs from Congress: it co-opts local elites and opponents

Concluding thoughts

For the moment, the sheer centralisation in welfare delivery, and the advertising around it, seem to have generated great distinctions between state and national elections. But these differences are partially due to removing the “old guard” of BJP-aligned chief ministers that built their political appeal upon welfare delivery. Nowhere was this more apparent than the recently concluded 2020 Bihar state election. Nitish Kumar has continuously served as chief minister of Bihar since 2005 and built his reputation on welfare delivery. In the 2020 Bihar election, Kumar’s JD(U) had a dismal strike rate of 37% as compared to the strike rate of 67% of its ally BJP—which was running completely on the visage of Modi. Not surprisingly, Nitish Kumar said that this was the last election. The political and economic centralisation around Modi has all but cleared out welfarist chief ministers before the Modi era. I suspect the next generation of BJP regional leaders, much like Yogi Adityanath, will likely look to establish their credentials not in welfare delivery but in Hindu mobilisation.

End Notes:

- I count the one seat contested by the All Jharkhand Students Union (AJSU) allied with the BJP in this total.

- I have refrained from providing winning vote shares across years as they are confounded by vote splitting with the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and independent candidates.

- These data have been graciously provided to me by Shamindra Nath Roy at the Centre for Policy Research.

Neelanjan Sircar is a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR). He also teaches at Ashoka University. Views are personal.

This article first appeared in the journal Economic & Political Weekly (EPW).

For all your analysis/paralysis, Modi didn’t alter any Center-State balance in terms of their respective welfare reach to the poor. All he did was to launch the old schemes firmly & just ensuring that they get delivered to the destination properly, the delivery part making all the difference between him & his predecessors. You must only credit him for choosing the right initiatives that impinge on the daily lives of common people such that they feel immensely served. States were doing their welfare schemes as before. Any scheme done without focus & attention tend to go astray with a lot of vested interests coming in the middle of deliverance – typical case being MNRGA under the administration of UPA. Going by your logic, states ruled by non BJP parties are able to retain their power only by being castiest or other such means & not based on how they serve their people for their livelihood. And you say Yogi is an exception & is popular because he is pursuing hardline hindutva, forgetting the fact that UP elections were won much before Yogi became CM & he is yet to face a general election for the state. UP was a case where BJP improved on their Loksabha performance without a CM face!

In all this, your mind deliberately wants to ignore the one most important aspect that propels Modi as a unique leader seen by people at large as worthy of their trust – that is he isn’t corrupt. Despite mammoth attempts to paint him as corrupt in Rafale deal with half knowledge & full maliciousness, Raul Gandhi had to bite dust when SC ruled clearly that the deal concluded by Modi Govt is less expensive on a comparable basis. Even though Raul was trying to go to town with allegations of Ambani being favored, the knowledgeable crowd always knew the nature & extent of off set contracts awarded. Even media could know easily but they chose to remain on surface to promote more fun & excitement dishonestly. Truth has a way of coming out & it came out to establish that Modi is blemishless. Tell me is it so easy to find a leader today who won’t do below the table deals? Couldn’t people be so happy & satisfied that they found one at last? Nothing kills people’s lives & livelihood more penetratingly than corruption at top levels & country had in the past seen corruption reaching sickening proportions. Do you even know why the inflation had been so low in the past 7 years despite oil prices not being slashed in line with international prices, putting more value in common man’s pocket for the income he earns? That’s exactly the result of absence of corruption. People are seeing for the first time a leader who stands for their livelihood & country’s interests. Isn’t it remarkable in itself that such trust must find a reflection at polls particularly when the alternatives remain so dangerous yet. Think beyond your bubble.

Like bone which is thrown to a dog so that it can keep it chewing in pursuit of juice, Modi’s presence and moving from strength to strength is itself a bone to chew for Nilanjan Sarkar kind. Modi gets repeatedly elected because people trust him. People trust him because he is seen to be honest to the core unlike the corrupt Gandhi family and moat importantly Modi delivers to the last man (antyodaya). Toilets, DBTs, Electricity, Gas cylinders, good roads, and now he is working on ambitious project of water through pipeline in every home. All this requires hard work, requires brain to think and work on ideas. A duffer who makes wild charges everyday and whose family kept the poor of this country poor for 60 years is not expected to be of any use to the aam admi of this country. Yes and Modi is also seen as someone who has aroused the dormant nationalism spirit in many. Plus removal of 370, his patience on Ram Mandir, getting a legitimate decision through the highest court of the land all have contributed to his no non sense image. The Nilanjan Sarkar’s may keep continuing chewing the bone for a long time. Modi will come back with a bigger mandate in 2024. And after him will be Yogi for next 25 years. Enjoy the heartburn Lutyenswallahs.

Well said!! The tukde gang needs a proper laundry wash to discard their brown British & Pakistani Indian attributes!! They should be happy that Indians & the BJP are giving them this chance unlike Congress & gang which killed opposition leaders & voters to sustain power and please their petty Islamic & Vatican vote banks!!

Who can forget Jan sang’s leader S.P Mookerjee’s murder by congress installed Islamic terrorist government in Kashmir?? Nehru even refused to do an inquiry and thus proved that he was directly responsible for this murder!! There are so many others instances where they did the same to patriotic leaders & carried out genocide of people; especially Hindus!!

Centralized benefits helped last mile delivery achieve 100%. Instead of intermediates eating away or going preference to their electorate. It’s a equitable delivery irrespective of caste, religion. Instead of celebrating the author is complaining. BTaw I am not a big fan of these dole outs. I wish BJP use this money to develop economy.

“While there is no clear evidence the schemes under Modi have been more effective, there is little question that the BJP engaged its impressive party machinery in advertising these schemes and building the perception that Modi directly delivered benefits to the voter (Aiyar 2019). “. This is the crux of this excessively long write -up. Voters are fools who despite receiving no benefits have given such a high approval rating to Modi. No need to read after this.

@Vish: Correct!! Only the commie/Jihadi Khan market gang knows it all!! Indian public; especially Hindus are stupid!!

1. Welfarist politics is here to stay inspite of whatever bhakts and other sundry supporters of the BJP have to say. For all of Modi’s pitch on market based economic policies, he is as committed to welfare as any PM before. The only time he actually speaks of market economics is when he has to sell an idea which may benefit his own billionaire benefactors. Small businesses have been thrown to the wolves as much as landowning farmers.

2. The last line is very revealing. Look at Shivraj Chauhan/ Yediyurappa trying to ape Yogi. This is the way the wind is blowing in the BJP for sure. Muscular religion based politics will be all the BJP has to offer. No wonder the economy is in doldrums. Worse days may follow if we continue on this path.

3. Two extremely damaging trends have been set forth by Modi himself.

a. His “Harvard vs hard work” remark has condemned education and expertise in public life. Talented, educated people with exposure to the wider world and ideas will hardly be interested in contributing to public good if politicians and leaders don’t value them.

b. His misuse our great Hindu religion for helping himself first to consolidate the CM chair in Gujarat and then acquire the PM chair in Delhi has put all of us in peril. Hindus will also be in danger of being labelled like Muslims as religious fanatics if we continue to let Modi use his illiberal divide and rule brand of politics to damage our country’s and our religion’s reputation in the wider world.

Hinduism is not a religion.

Hinduism is dharma based way of life unlike Islam & Christianity which are rather violent political ideologies marketed as religion!!

Ha!! Ha!! Muscular religion based politics will be all the BJP has to offer?? Really??

Ofcourse those were Hindus or perhaps Christians who created Pakistan for Islam & yet stayed in India to drink Gaumutra!

The genocide of Hindus by Jihadis through out history as lately in Kashmir or Pakistan/Bangladesh today & congress’s record of Hindu genocide is not proof enough that they have been worse than jungle pigs!!!

Of course Muslims never vote en bloc like cattle & brainless zombies!!

Interesting.

Now if the Congress can send the Gandhis packing, BJP would be in substantial trouble.

So much for India becoming an autocracy. The current political environment is just undergoing it’s natural cycles. Nothing is permanent.

yes it is cycles – like the way mentioned in the book “Fourth Turning”

If congress can stay in power for 6 decades despite their genocide of Hindus, BJP or another right wing party can stay in power for a century or more!! Creation of terrorist Islamic Pakistan & keeping most of those terrorist voters in India is a crime for which they haven’t yet paid a price!! If BJP was like congress & those Jihadis who have been killing Hindus since eons, Rahul Vinci Khan’s family would have been in graves eating poop!!

Dream on!! Congress was a British Christian, white supremacist creation!! It was as good as dead in 1947 had MK Gandhi not hacked democracy by bringing that UN-elected, incompetent Pakistani Nehru to power!!

Centralisation of welfare schemes worked fabulously. Look how bank accounts, toilets, gas connection, electricity connection penetration increased to 100 % in the last six years.