What is remarkable about the 2019 Lok Sabha election is that the very nature of the contest is under contest.

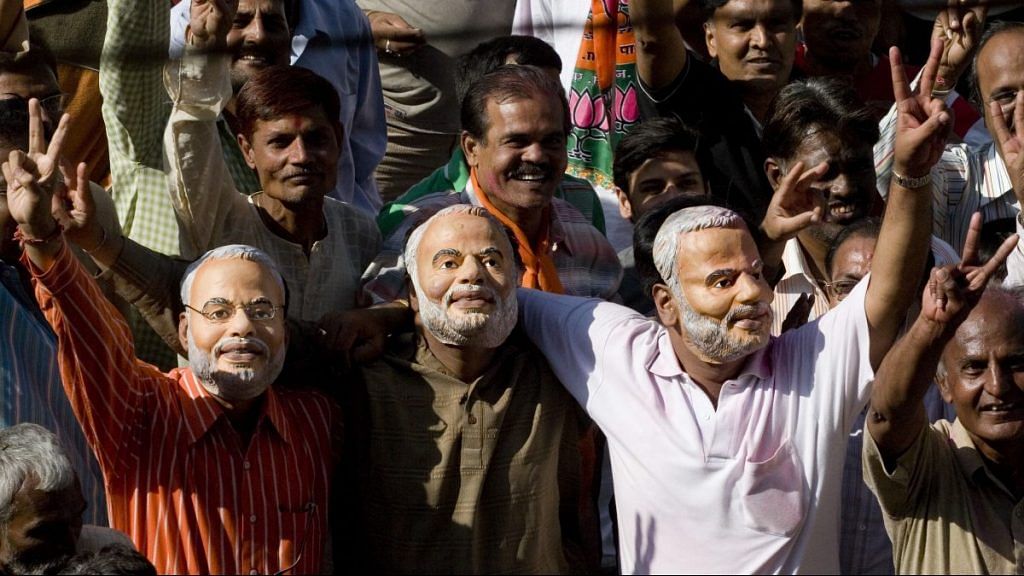

On the face of it, the BJP is asking people to give Narendra Modi a second term as prime minister, while the Congress and other opposition parties are campaigning to topple him. Yet below the surface, the BJP is essentially running a presidential campaign in a parliamentary election, as if the Lok Sabha were an electoral college that will place Narendra Modi in the chief executive’s seat. This is not surprising. Having run a nearly presidential government for the past five years, Modi quite likely wants to continue in the same fashion.

If the BJP wins again India is quite likely to have a government that is parliamentary in form, but presidential in substance. This would be quite a radical departure from the constitutional scheme that sees the prime minister as the first among equals.

Also read: The Presidential Prime Minister Narendra Modi

Unlike what many people have come to believe, members of the council of ministers (the cabinet) have complete authority over the ministries they head. The prime minister is the head of the council of ministers and chooses his or her cabinet colleagues, but the council as a whole is collectively responsible to the Lok Sabha. While some prime ministers, like Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Narendra Modi, have dominated their cabinets, the Constitution does not envisage an all-powerful PMO that directs individual ministries on policy matters.

The relationship between the prime minister and his or her cabinet colleagues is not one where the latter are subordinates. Modi changed this in practice once he became the prime minister in 2014. The BJP’s election campaign promises the voter more of this should the party return to power.

It is, therefore, just as well that the Congress and other parties opposed to the BJP are not offering their own presidential candidate. Partly by design and partly due to circumstances, the fact that the opposition is not putting forth a strong, unequivocal prime ministerial candidate ensures that the election remains parliamentary, as it is meant to be.

While the election rhetoric might suggest that this is a referendum on Modi as the BJP would have it, or a manifesto for a new welfare state that the Congress promises, the deeper choice is one between majoritarianism and redistribution. You can’t compare apples and oranges, but as voters, we’ll still have to choose between them. How will either of them tackle the smog of resentment, grievance and anxiety that has settled on the country over the past few years? How will either of them generate economic growth? Majoritarianism without growth will devour its own, while redistribution without growth will drive us to ruin. Days before the elections, we have no idea what the BJP, Congress and the others will do to restore economic growth.

Also read: Narendra Modi and jobs: It’s all about data, and how it’s calculated

India’s biggest short, medium and long-term challenge concerns jobs. The real scandal is not the lack of jobs data, but the lack of jobs. The required run rate is 20 million jobs per year; our best and current run rate is 2 million per year. In other words, we need a ten-fold jump in job creation. That is the only way we can address rural distress (by getting surplus rural labour out of agriculture), urban underemployment and provide meaningful occupations to the millions of people entering adulthood every year.

This is a challenge that is unprecedented in scale and scope and missing from the electoral debates. We are offered more nationalism and more redistribution: neither of which is a way to generate massive employment. We are like a patient who needs to select a surgeon to carry out a complicated operation, being asked to choose between a good-looking doctor and a guitar-playing one.

Also read: Why voters don’t turn up in larger numbers in Lok Sabha elections – all politics is local

It is both lazy and irresponsible to conclude that all options are equally bad, so let’s just vote ‘none of the above’. That would be a cop-out. It could also put in place a government worse than we might have willfully chosen.

There is a local dimension to our political choices: In fact, it is on this that we actually exercise our franchise. Sending the best person, or the least worst person, on the ballot to the Lok Sabha is an important and useful thing to do, in itself.

Ultimately, there is also a moral dimension to our political choices, and it has an important role to play at these times.

The article was written before the Congress published its manifesto.

The author is the director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy.