In times of job crises, top members of the Narendra Modi government always agree on one thing – the data is a problem. Specifically, data on the informal sector, which dominates the Indian workforce.

“Indian informal sector employment has not been appropriately or exhaustively documented. When we are referring to data from government organisations like NSSO, it talks only about the formal sector and not about the informal. In India, the nature of our economy was that it is in the informal sector where majority of our employment is,” said Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman earlier this week in Chennai, while responding to fears of an economic slowdown.

In February this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a combative speech to Parliament before the 2019 elections insisted that jobs were being created, contrary to a then-leaked report that said unemployment was at a 45-year high (data that his government subsequently officially released the day after coming back to office). These jobs were just not being properly counted, he said. There was “no correct system of collecting job data” at the moment, he said, and his government was trying to put one in place.

Also read: Modi govt didn’t address jobs crisis in the first term. India’s progress depends on it now

This is news to anyone who uses the government’s own labour data on a regular basis, because India’s official employment statistics are, on the contrary, almost entirely about the informal sector. If anything, we know very little about white-collar workers with job benefits or entrepreneurs who pay GST because they form such a small share of the official statistics that they have so far remained undifferentiated.

The simple reason for this is that India’s employment and unemployment data comes from the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), the redoubtable government agency that has been conducting large-scale sample surveys since 1950 to a degree of excellence certified by the world’s leading data agencies. The NSSO’s employment reports are household surveys, where enumerators visit a sample of respondents, statistically sampled to be representative of the country, and seek details of their participation in the workforce.

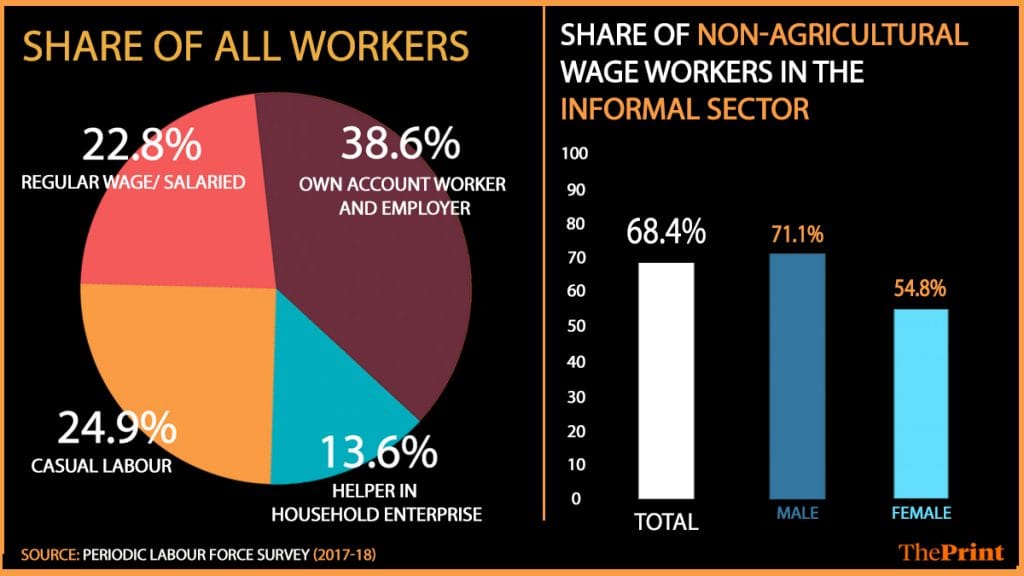

Here’s what we know. The Periodic Labour Force Survey (2017-18) that the first Modi government withheld until it won re-election showed that over half of all those in the workforce are self-employed, another quarter work as casual labour, and the remaining are wage workers or salaried workers.

Also read: New data explains the unwavering support for Narendra Modi despite sagging economy

If self-employed sounds like a Bengaluru entrepreneur who you would imagine belongs to the formal economy, there’s this from a 2009-10 employment report by the NSSO: “Among self-employed in non-agricultural sector, about 92 per cent in the rural areas and 95 per cent in the urban areas worked in the informal sector”. If formal jobs are understood as those with contracts, benefits, leave and regular hours of work, it becomes clear that the majority of jobs in the agricultural sector are informal.

From the same 2009-10 report: “Among casual labourers engaged in works other than public works in the non-agriculture sector, nearly 73 per cent in both the rural and urban areas worked in the informal sector.”

Meanwhile, from the 2017-18 PLFS, over two out of every three salaried jobs in the non-agricultural sector – including all salaried, professional white-collar workers – are in the informal sector.

Also read: Better data can improve public education in India – draft National Education Policy says it too

None of this is to say that the NSSO couldn’t do a better job of collecting data in the informal sector (just as it should do a better job of categorising the professions of the super-rich). The NSSO has itself constituted numerous committees, which come out with dense reports on ways to improve its informal sector data. The PLFS, which the government has largely ignored thanks to its unflattering numbers, was supposed to be one step in this direction.

But attributing every flaw in the labour market – high unemployment, the fear of job losses, a freeze on hiring and bonuses as the economy stands spooked – to a lack of data has to be called out for what it is: a predictable and false diversion.

The author is a Chennai-based data journalist. Views are personal.

If 38% is on own account worker and employer, I have a Taj Mahal for sale for you. Even stretching Pakodanomics so much is silly.

Who would have the best understanding of what is going on in the informal economy or people who do not hold regular jobs in the organised sector ? An MP, MLA, member of an urban or rural body like the Panchayat – someone who does not chopper into Mathura like Hema Malini does once in five years – meets these folk on a continuing basis. Understands their problems. Helps them out in small things. If large swathes of the Indian economy look like they have been hit by a meteorite, how can those who claim to have a finger on the pulse of the people not know what is going on. Jaan ke sab kuchh, kuchh bhi na jaane, Hain kitne anjaane log …