Marathas are a large agrarian Shudra community in Maharashtra, constituting nearly 30 per cent of the state’s population. Maharashtra’s economic development, to a large extent, depends on the well-being of this community, along with other Shudra agrarian communities. The five-judge bench of the Supreme Court while striking down the 16 per cent reservation given by the state government has said that the latter had not cited any extraordinary conditions before allowing this reservation over and above the 50 per cent quota stipulated in the Mandal judgment of 1992. The court did not take into account the caste-varna system, which still functions against the idea of equality even in the case of a major agrarian community such as the Marathas.

The Marathas seem to have realised that despite the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), whose ideological parent is the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), being in power since 2014, the community is still confined to the varna inequities. They could not compete with the Dwijas (the non-Shudra upper castes) in all-India services or in state services, one of the avenues available to them for their socio-economic upliftment.

Many agrarian Shudra communities in India, like Marathas, Jats, Gujjars, Patels, Reddys, Kamms, Nairs among others, did not opt to be included in the Backward Class list in 1992. But some of them now realise that they cannot compete with the Dwijas (Brahmins, Banias, Kayasthas, Khatris and Ksatriyas) who had the historical resource of education in Sanskrit, Persian and English for a long time.

Also read: New backward class lists to be drawn, 50% ceiling stays — what SC Maratha quota verdict means

The leadership vacuum

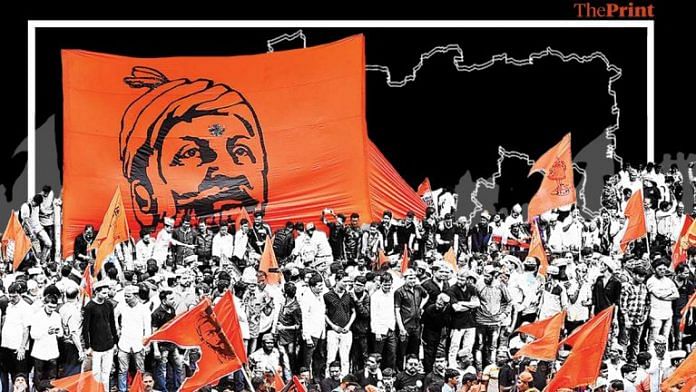

Having played a mass-mobilisation role in the Hindutva movement in Maharashtra, the Marathas aspired to get their share in Delhi’s power pie if the RSS/BJP combine formed the government. But that clearly did not happen — the Marathas seem to have realised that they are nowhere in Delhi and their power influence is limited to Maharashtra. Not just the Marathas but many other agrarian Shudra communities who remained outside the Mandal list have a similar realisation.

From the same state of Bombay, before its division into Maharashtra and Gujarat, Brahmins and Baniyas emerged as national leaders, top bureaucrats, scientists and intellectuals. But the Marathas did not get to share the Delhi power. Though among the Shudras, Sardar Patel did emerge as a national leader from the Patidar community, no Maratha could. The Marathas now feel that such a top man/woman was not allowed to emerge during the freedom struggle and even later, till now by the Dwijas. The RSS structure has shown them that control. Though many Brahmin Maharashtrians headed the RSS, not a single Maratha was allowed to reach at the top. They were confined to agrarian production, agribusiness and local power with a new definition of unified Hindu. Marathas were used mostly as muscle power against the minorities by the RSS.

After the exception of Mahatma Phule, who emerged as an early intellectual from the Kumbi Maratha community, India saw a stream of Brahmin leaders and intellectuals in the subsequent years from the Bombay province. While Mahadev Govind Ranade, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi (of Bania background) emerged from one stream, V.D. Savarkar, K.B. Hedgewar, M.S. Golwalkar and now Mohan Bhagwat came from the Hindutva stream — all Maharashtrian Brahmins and powerful national leaders.

The Marathas have not produced English-educated top national leaders and high intellectuals. This proves they were/are educationally backward. The Shudras, historically, were not supposed to learn, read or write Sanskrit. This historical limitation got carried to Persian learning as well during the Muslim rule. Even the modern English medium education eluded the Marathas — true of all the regional Shudra communities, except the Nairs of Kerala.

Also read: MVA-BJP blame game begins after SC Maratha quota order, Uddhav nudges PM for ‘speedy decision’

The historical gap

The Supreme Court must consider the history of caste while formulating the idea of equality. How else could one explain the inability of the Shudra upper layer castes, who outnumber the Dwijas, in competing in the all India services. This is a limitation that history has placed on all Shudra communities — they are rural and have agrarian and artisanal backgrounds. How does the highest court not take this historical factor into account?

One must know that the Marathas were spread over vast rural productive land. It was the Brahmins, Baniyas and Kayasthas (who had limited presence in the province), who became early urban settlers in the Bombay province. This was also true of Calcutta and Madras provinces. English medium education was an urban phenomenon. The Dwija castes benefited from that urbanised English education life. Even the early Christian institutional English medium education benefitted only the Dwijas. This is very clear from their overwhelming presence in all national and international English-speaking platforms, and from the near absence of the Shudras.

The judiciary should not commit the same mistake that the Indian Communist theoreticians did. They looked only at the land ownership and not the power of the written word. The Shudras of India owned some land and labour but not the power of the written word. Apart from the power of written word, the Brahmins of Maharashtra, particularly Desais and Sirdesais, had control over land resources. In parts of British India, Brahmin zamindars and jagirdars controlled the whole life — spiritual, social, economic and political — of the Shudra masses.

The idea of reservation is to distribute the power of the written word. All Shudra castes, including the Marathas, lack in this area, particularly English and the English-medium education. In all central services, judicial services and media, the power of written word placed Dwijas in advantageous position.

This is why it is important to relook at the 50 per cent ceiling of reservation in central and state services, and education. The debate on this limit should continue until caste and varna differences are abolished. Their abolition is now into the hands of the RSS-BJP, who claim to represent all Indian Hindus, and not just the Dwijas. Granting spiritual and social justice to all Shudras and Dalits is their duty. But they are not working towards that goal. This is the biggest worry of the Shudras.

The Supreme Court gives many legally enforceable judgments but does not ask for caste census. Why? The caste census gives a clear direction about every caste’s representation in every institution.

The court’s power is also located in the written word. And that power must also be distributed among all communities. Else both social and natural justice will suffer.

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd is a political theorist and social activist. His latest book is The Shudras — Vision For a New Path, co-edited with Karthik Raja Karuppusamy. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)