Madhya Pradesh is India’s worst-performing state in basic areas of governance such as health and education. Even within the context of North India, it performs poorly. Comparing Madhya Pradesh with Kerala, India’s best state in terms of health and education, misses a crucial point: it does significantly worse than Bihar, one of India’s poorest states.

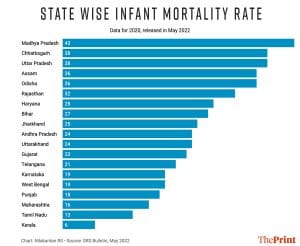

Madhya Pradesh had an Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) of 43 per 1,000 in 2020, the highest in the country. On the other hand, Bihar did much better with an IMR of 27 per 1,000 for the same year. Why does Madhya Pradesh do so badly? And why is Haryana, a rich state, in the same boat?

The IMR is a basic measure of governance for a developing society. It’s a robust indicator of basic governance as it is the outcome of several input metrics that measure how well a government did its job in the recent past. It is also a predictor of how well society will turn out in the future.

How well a state does in terms of its IMR is correlated with how rich it is, how well it manages to send its girls to school, how many hospitals and hospital beds it has per million of the population, how efficiently pregnant women are cared for, how children are taken care of in terms of nutrition after birth, how many villages have functioning primary healthcare centres (PHCs), how many of those have doctors, and so on.

Also read:

Madhya Pradesh and Haryana fare worse than Bihar

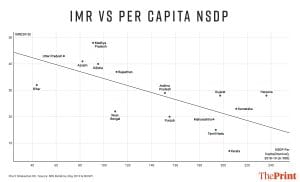

There are a few exceptions here, though. Haryana, a prosperous state by Indian standards, has an IMR significantly worse than its economic indicators predict. Its story is, in many ways, a grotesque one, given how many infants die in the state despite it being rich enough to prevent those deaths. We can measure how badly Haryana does in this regard by looking at its positive residual from the regression line in the chart above.

A simple regression chart between the IMR in each state and the per capita Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) reveals how badly Haryana and Madhya Pradesh do. Bihar, a poorer, less educated and less urbanised state, does much better than Madhya Pradesh. And stunningly, Bihar does almost as well as Maharashtra, India’s wealthiest state.

So, why does Madhya Pradesh have such bad outcomes compared to Bihar?

In terms of basic health infrastructure, Madhya Pradesh boasts better metrics than Bihar. For instance, compared to Bihar, it reaches more pregnant women for antenatal care, and has more hospital beds per capita. It also has more Aanganwadis in ‘pucca’ buildings and has fewer stunted children suggesting slightly better nutrition rates. While all of this is true in terms of hard infrastructure, the one data point where Bihar does better than Madhya Pradesh is the number of registered doctors. Bihar had 637 doctors per million of the population, while Madhya Pradesh had 473. And unsurprisingly, the other state with such a large residual on the chart above, Haryana, also has an abysmally low number of doctors per million of the population, at 71.

Unfortunately, wherever there is a shortage of doctors, the IMR also appears tragically higher.

Also read:

Admit more doctors

What should states like Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh etc., do to improve their status then? The answer is relatively straightforward: they need more doctors. And they need these doctors to serve in the rural hinterland, where the IMR is relatively higher.

One way to increase the supply of doctors is to broaden entry criteria and build greater capacity instead of worrying about “merit” at the time of admission. The successful states in India did this a generation ago, and the results are there to be seen. After all, a society struggling with an IMR that’s as high as sub-Saharan Africa does not have the luxury of restricting access at entry point. But to get a greater stream of people to join medicine, these states must first fix their high school enrolment rates.

More importantly, they must look at health outcomes at the state level and apply fixes there. That Bihar and Madhya Pradesh would need different solutions to fix the same problem given where they are is counter-intuitive. Bihar needs more material, while Madhya Pradesh needs more personnel. The data shows that this country’s central and northern plains aren’t a monolith, either. More urgently, maybe Haryana needs to pay doctors from other states to relocate and serve in its rural parts, given it can afford to do so.

Why a state does better than others is a function of factors specific to that state. Their policy response, thus, has to be equally specific. The problem is that the central government seems to consider national policy response as the only apt solution to such issues. A classic example is the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) – an insurance programme – as a policy response to India’s healthcare accessibility problem. Using the financial engineering approach to fix healthcare in places where there aren’t enough doctors is akin to searching for one’s lost keys in the light, and not on the dark spot where one actually lost them.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)