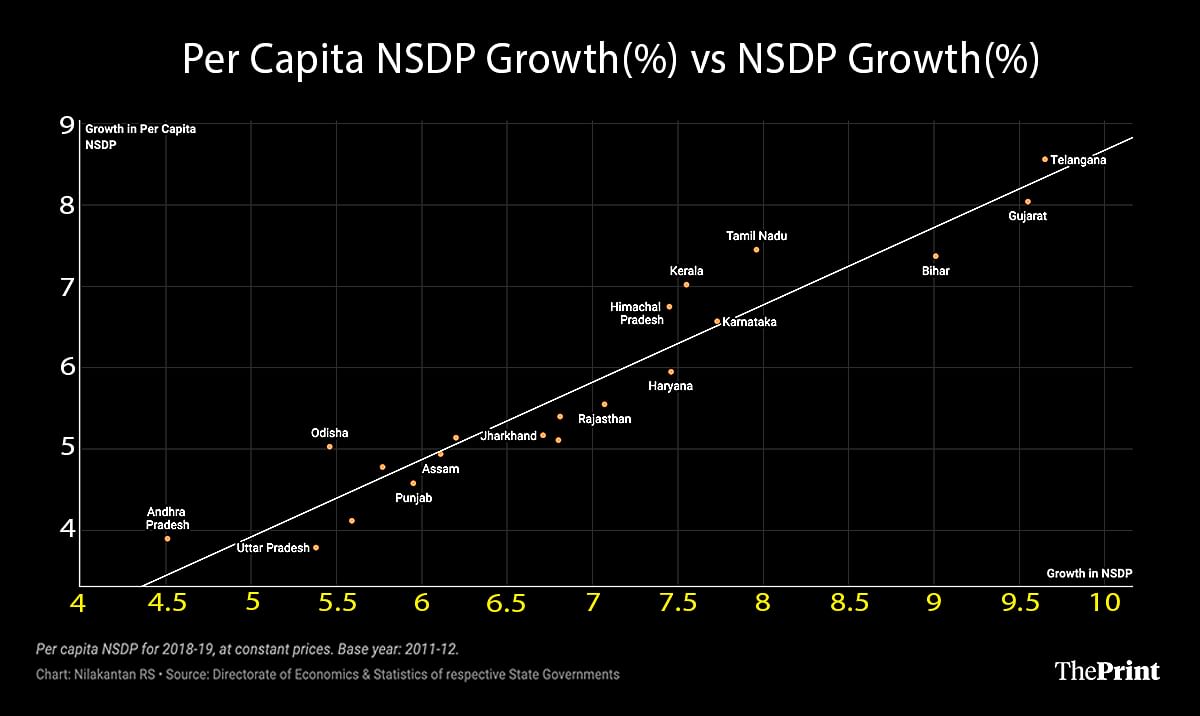

Consider the pre-pandemic year of 2018-19. If we take the growth in Net State Domestic Product—annual economic output–and the per capita growth of NSDP for each state, and plot a simple regression chart between the two, we see the starkness of India’s divergence.

Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state by population, had a NSDP growth of 5.38 per cent while its per capita NSDP grew by 3.79 per cent. That is, the state does not realise all its economic growth in its per capita growth; largely because its population is still growing at a significant clip.

Uttar Pradesh’s economy has the greatest negative distance from the regression line, also called the negative residual. In other words, the state would have the least growth in per capita income if absolute economic growth were constant across all states. A similar exercise can be done for all states.

At the other end of this spectrum is Tamil Nadu, the state with the highest positive residual. That is, the state realises most of the economic growth in NSDP as per capita income because its population has largely stabilised. Other states with a positive residual are Kerala, Odisha, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana. They do better than India as a whole in terms of realising their economic growth as per capita income. Meanwhile, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh and others with a negative residual have to grow even faster than India for their citizens to feel the growth.

Also read: India’s large villages at risk of losing out on development due to ‘rural’ tag: Experts

Rural population of Indo-Gangetic plains

The negative residual shows how a difficult problem is made worse for states such as Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar among others. In these states across the Indo-Gangetic plains, a vast majority of the population lives in rural hinterlands. And most of them depend on agriculture for a living. Their yields are so low that it makes achieving economic growth impossible without moving people out of rural places, away from agriculture into manufacturing and services. The population growth in such states makes agriculture even more unviable. By reducing land holding sizes, it places a burden on already strained social services and makes the population less ready for taking up higher value jobs. Above all, the little economic activity they do generate ends up having to cover for an exponentially increasing number of people. That is what shows up as a negative residual in the chart above.

The population growth of the states with a positive residual, one can see, have all mostly stabilised. They have had below replacement fertility rates for a while now. And their dependence on agriculture is far lower than the states in Indo-Gangetic plains. The citizens have moved out of rural hinterlands in larger numbers. Kerala and Tamil Nadu, for example, have a greater proportion of their population living in urban areas than in rural parts. Even their rural population isn’t as dependent on agriculture.

The purpose of economic growth is for people to make economic gains; not for countries to move up on global ranking lists that make no sense. If we are measuring mere absolute GDP growth that isn’t even realised entirely as per capita income—because population growth eats into it—gloating about being the fifth largest economy is pointless. What we should do instead is rank states on per capita incomes and compare them to other countries so that we get a better idea of their relative standing and the extreme divergence within the country.

Full picture behind data points

India pipped the United Kingdom to become the world’s fifth largest economy. But if someone were given a choice to be born between these two countries, just on material grounds, they would blindly pick the latter. India has a population that’s orders of magnitude larger than the European countries it eclipses in terms of economy. More importantly, India’s population is still growing at a fast rate while those smaller countries have stabilised populations for half a century. What’s even more significant is the fact that India is still very poor compared to the rich European countries.

The extent of news coverage on and the spin that incumbent politicians apply to take credit for what’s inevitable make one wonder what happened to a country that used to lay extreme emphasis on arithmetic in school. The real non-trivial part of the demographic story in India lies in the extreme divergence among states in terms of population growth and its impact on their prosperity.

Another data point that gets front page headlines is that the GST collections of each month is higher than the previous month. Inflation–even in zero real growth environments–will increase tax collection with each passing month. And we hopefully have some growth.

Politicians do something quite similar. They like to state how each year’s budget allocation is higher–in terms of absolute numbers–compared to the previous, even when the ratio of that allocation has gone down. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, during a visit to Tamil Nadu a few years ago, cited absolute numbers and claimed that the tax devolution to the state under his administration had gone up. What he didn’t say is that the allocation ratio of that tax devolution had gone down.

How does a country with its states as divergent as Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh make a national economic policy applicable for all? Should it even try? The answer seems obvious in that it shouldn’t. But can power ever realise its own limits? Sounds unlikely.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)