Efficient connectivity infrastructure is a prerequisite for regional economic integration. A 2018 World Bank study led by Sanjay Kathuria posits that trade between South Asian countries could be close to $67 billion, three times more than the actual figure of $23 billion. Various structural impediments, tariff and non-tariff barriers have limited the trade potential in the region, and in turn, affected regional integration.

Following economic liberalisation in the twentieth century, countries in South Asia have prioritised trade with distant European and Southeast Asian countries but have effectively maintained a closed border within the neighbourhood. For instance, it takes approximately two days for a container to be shipped from Kolkata port to Singapore (approximately 3,700 km), whereas it takes about the same amount of time for a truck at Petrapole Integrated Check Post (ICP) in West Bengal to cross the land border into neighbouring Bangladesh. Till the early 1960s, India, Nepal, and formerly East Pakistan (Bangladesh) were well connected through the waterways of Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers, and a large number of active rail services. Regional air connectivity in South Asia has also decreased significantly, with no flights between Nepal and Pakistan, or between smaller cities such as Port Blair (India) and Yangon (Myanmar).

As a result of this poor state of connectivity, which affected the region for decades, little attention had been given to improvements in border management infrastructure till the 1990s.

Evolution of India’s border management infrastructure

The push for improving land border management infrastructure began in India in 2000, in the aftermath of the Kargil War (1999). This led to the institutionalisation of border management through the establishment of the Department of Border Management in January 2004 under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA, 2004). During this time, a security-oriented approach to border management was dominant, and discussions were held by a Group of Ministers (GoM) on the setting-up of border management infrastructure to check illegal activities.

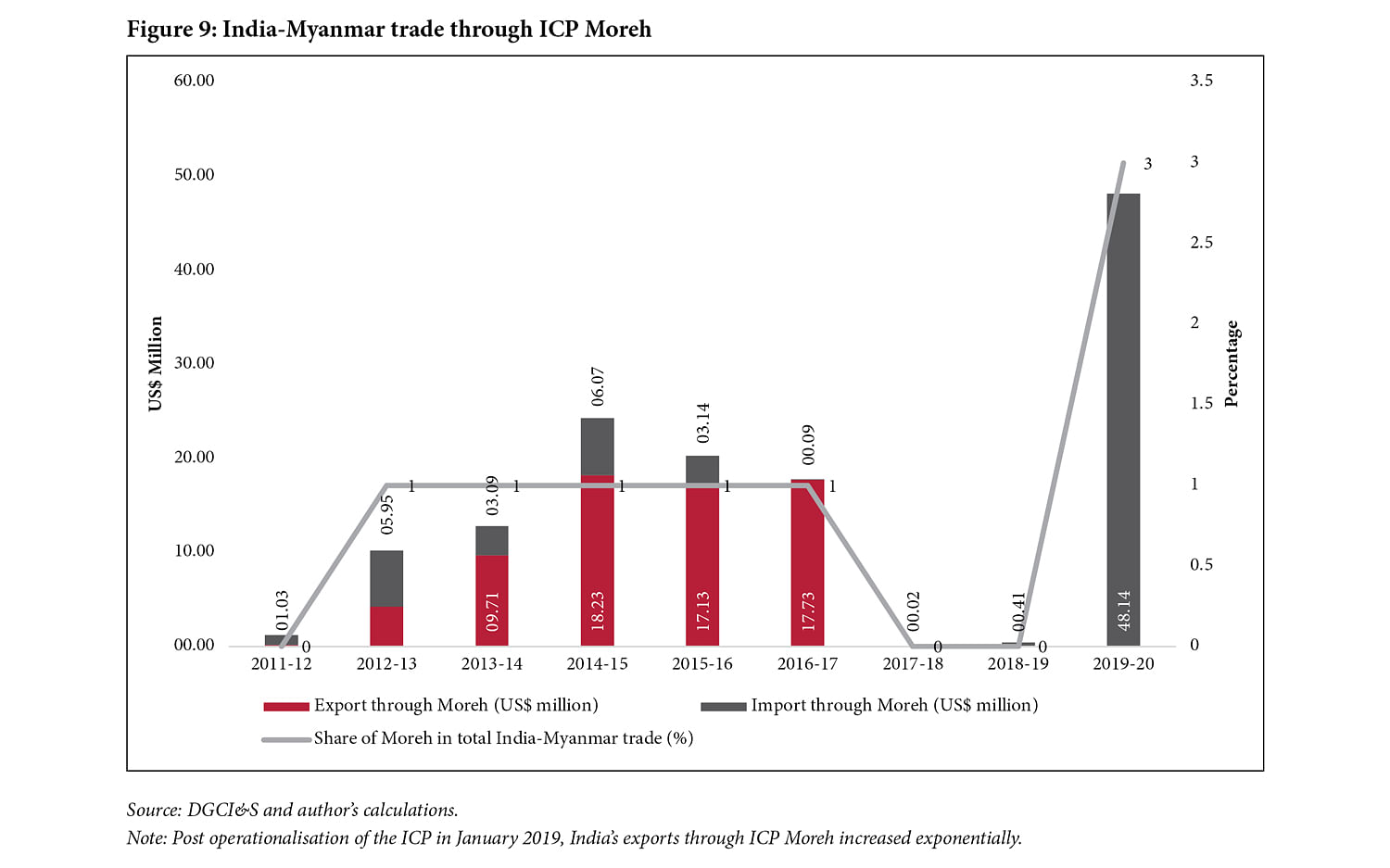

At the India–Nepal border, the GoM recommended setting up Immigration Check Posts (ImCPs) and Land Customs Stations (LCSs) at all transit points linked to Kolkata Customs, in order to check the illegal movement of people and goods; between India and Bangladesh, the GoM called for ‘renewed efforts’ to formalise cross-border trade and check smuggling; and for the India–Myanmar border, it recommended the establishment of ‘a composite checkpost’ at Moreh. It would comprise customs and immigration facilities and be manned by staff from the federal Narcotics Control Bureau and the state police.

In the last decade, several other factors have also led to further modernisation of border management infrastructure through the establishment of ICPs. First, the rising trade between India and its neighbouring countries, the increasing volume of literature on the potential of economic corridors in the region, and the shifting focus among governments on using the South Asian countries as transit corridors—have all spurred further growth.

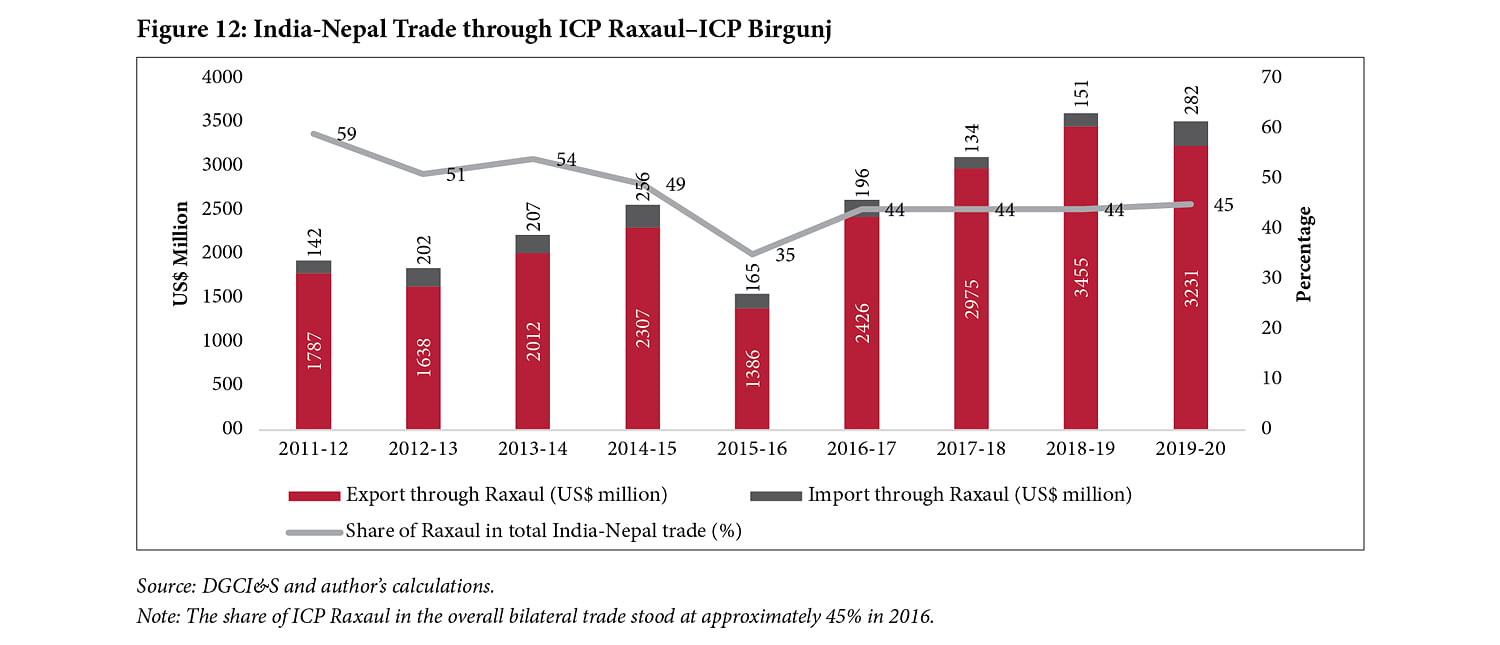

For most Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in South Asia, trade is at the heart of economic development. India is the market for approximately 70% and 90% of Nepal and Bhutan’s exports, respectively. Since the 2000s, India’s trade with Nepal has increased from US$ 0.3 million in 2000–2001 to US$7.9 billion in 2019–20. Furthermore, approximately 75% of Nepal’s and 100% of Bhutan’s global trade transits through India. These rising trade volumes necessitate improvement in border trade infrastructure.

Secondly, this is also driven by China’s growing investments in infrastructure in South Asia. India has been taking steps to correct decades of regional insularity with a focus on increasing connectivity with its neighbours, both at the regional and bilateral level. In this regard, the need to improve border management infrastructure was identified in the 2000s. This approach further accelerated under the ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy initiated in 2014, wherein improving regional connectivity infrastructure became a policy priority.

The development of the ICPs in India and its immediate neighbours is one of the key focus areas to improve connectivity. The ICPs in Northeast India are also important for the nation’s Act East policy, which is an extension of its 1991 Look East policy and is focused on integrating the Indian economy with the supply chains of Southeast Asia (MEA, 2021). Both policies have also led to the setting-up of mechanisms for monitoring infrastructure projects with neighbouring countries. For instance, after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Nepal in 2016, a Nepal-India Oversight Mechanism was put in place to oversee the implementation of bilateral projects.

Finally, improving cross-border trade infrastructure is also driven by India’s international obligations. In April 2016, India ratified the World Trade Organisation’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). India has also formulated a National Trade Facilitation Action Plan 2020–2023, to reduce the time it takes to release cargo from ports. The National Committee on Trade Facilitation (NCTF, 2020) set the target for clearance of goods from an LCS within 48 hours for imports and 24 hours for exports, by enabling paperless transactions and infrastructure augmentation. Additionally, in 2017, India also ratified the Transports Internationaux Routiers or International Road Transports (TIR) Convention. However, among India’s neighbours, only Pakistan and Afghanistan are signatories to it.

Also read: Land comes in the way of Modi govt’s Neighbourhood First and Act East, study shows

Integrated Check Posts: Their roles

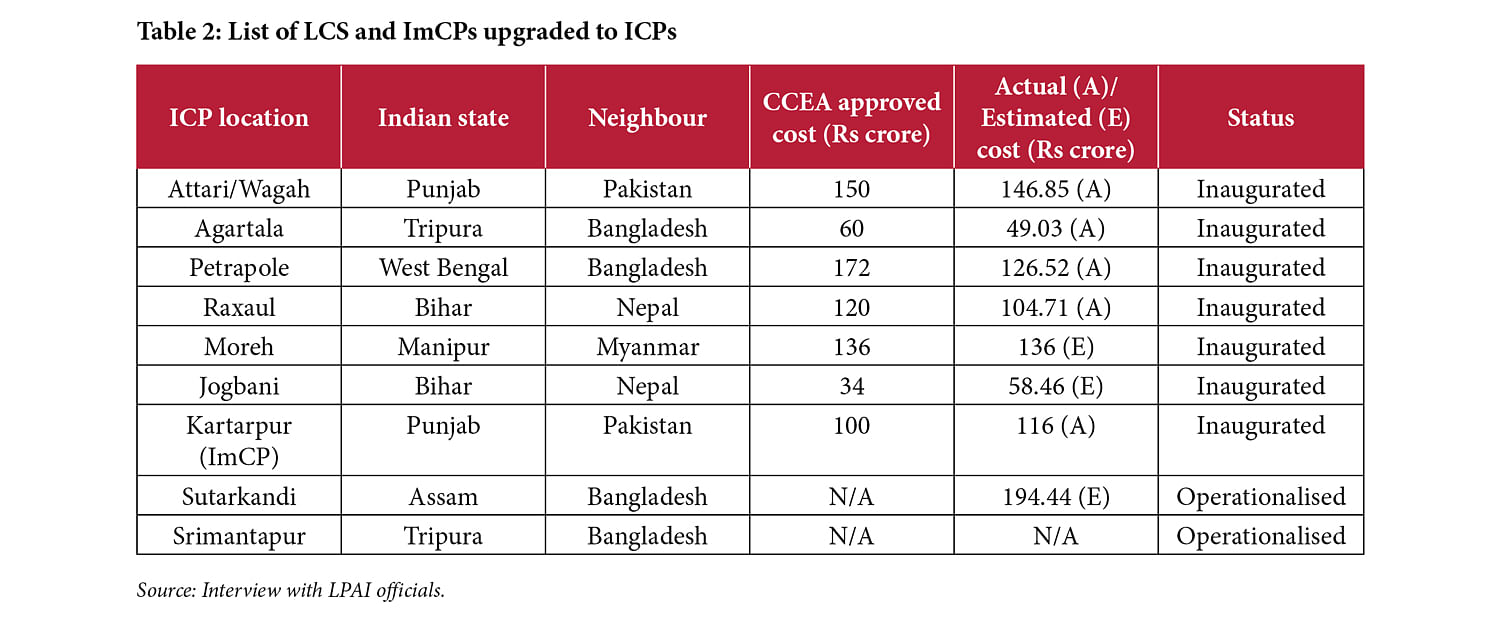

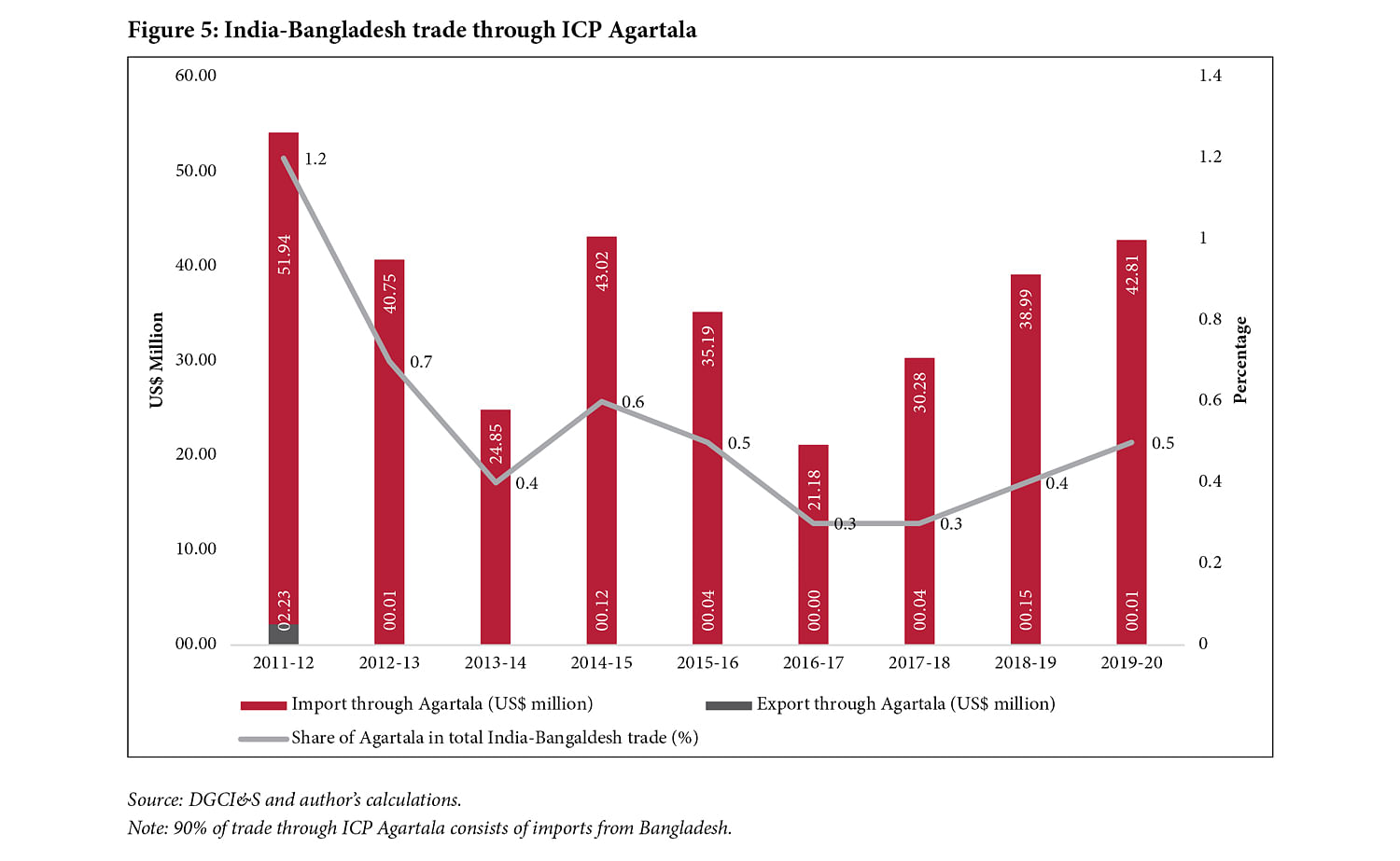

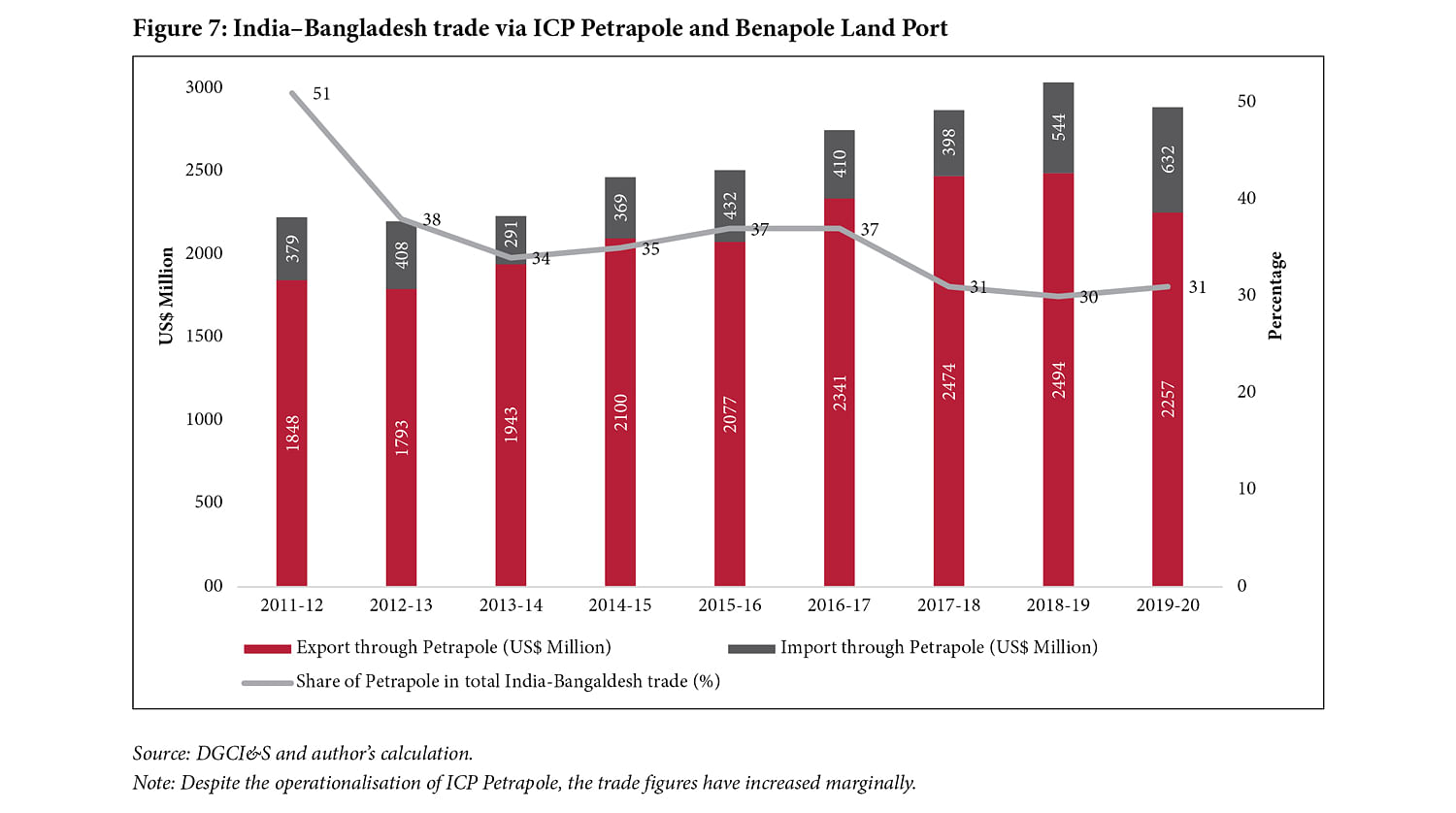

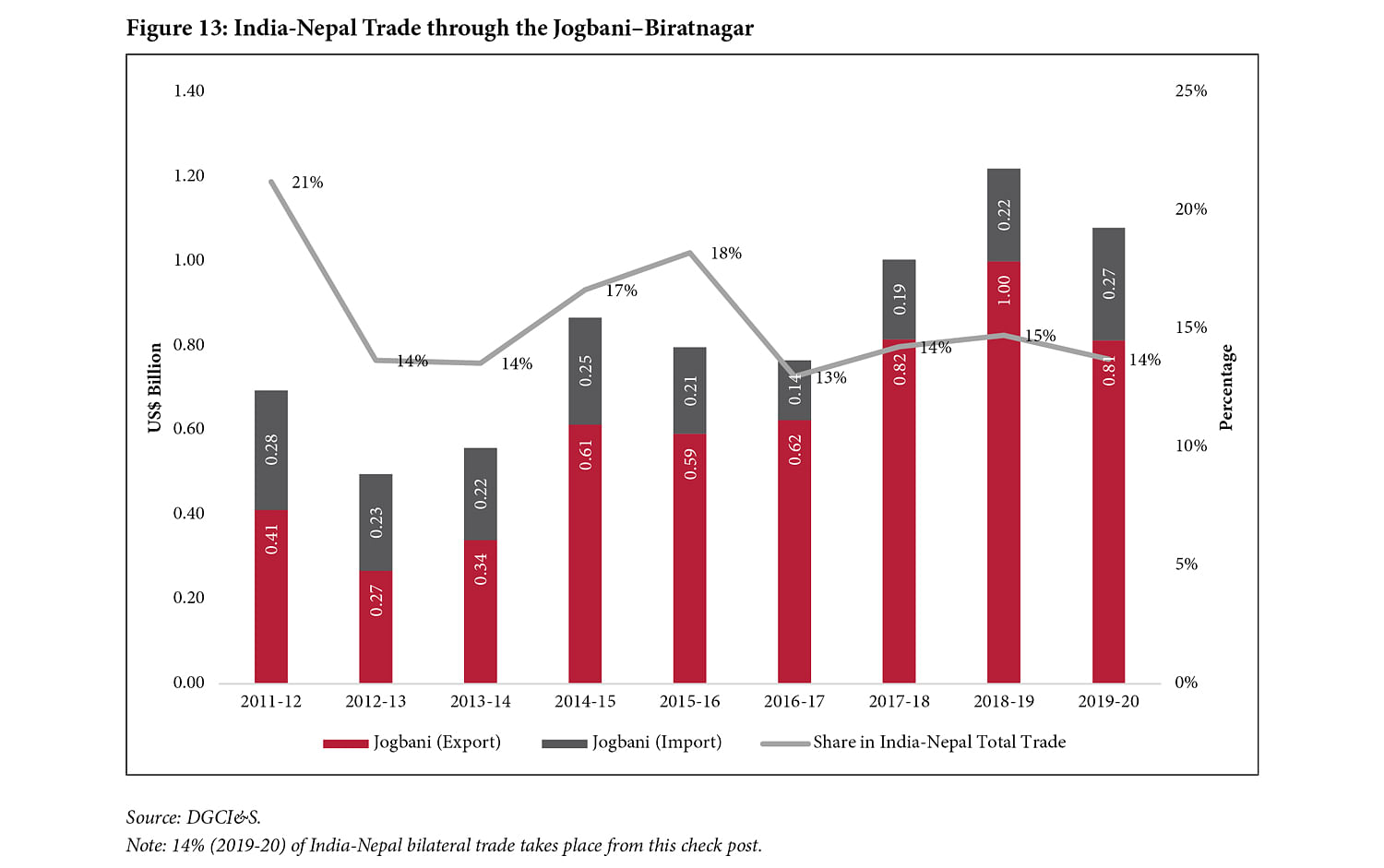

Since 2012, India has inaugurated seven ICPs at Attari, Kartarpur, Agartala, Petrapole, Raxaul, Jogbani, and Moreh. Out of these, Kartarpur is currently limited to passenger movement. India has also been constructing ICPs at Rupaidiha (Uttar Pradesh), Dawki (Meghalaya) and Sabroom (Tripura).

The ICPs are central to India’s connectivity plans in the region. They not only consist of border infrastructure for facilitation of trade and people, but also act as important centres to advance other multi-modal intra- and inter-regional connectivity initiatives, such as improving rail connectivity; implementing the Bangladesh–Bhutan–India–Nepal Motor Vehicles Agreement (BBIN-MVA); the use of Chattogram and Mongla ports in Bangladesh to transport cargo to India’s Northeast region; and the Kaladan Multi-modal Transit Transport Project to connect Southeast Asia to South Asia, among others.

Land-border crossings

Land-border crossings between India and its neighbouring countries are under two categories—LCSs and ImCPs. The ICPs consolidate both facilities within a single facilitation zone.

All LCSs fall under the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs. The LCSs are border crossings where trade in goods occurs between India and its neighbours.

The ImCPs are nodal points for facilitation of passenger movement across India’s land, sea, and air borders. India has 86 ImCPs, of which 37 are manned by the Bureau of Immigration (BoI), under the MHA and the remainder by state governments.

Integrated Check Posts

The Land Ports Authority of India (LPAI) is the nodal agency for construction, operation, and management of the ICPs. A customs station at an ICP performs the same functions as it does at an LCS, albeit with better infrastructure. At each ICP, the LPAI provides facilities such as a passenger terminal building, currency exchange, a building to process cargo, cargo inspection sheds, warehouse/cold storage facilities, a quarantine laboratory, banks, and scanners.

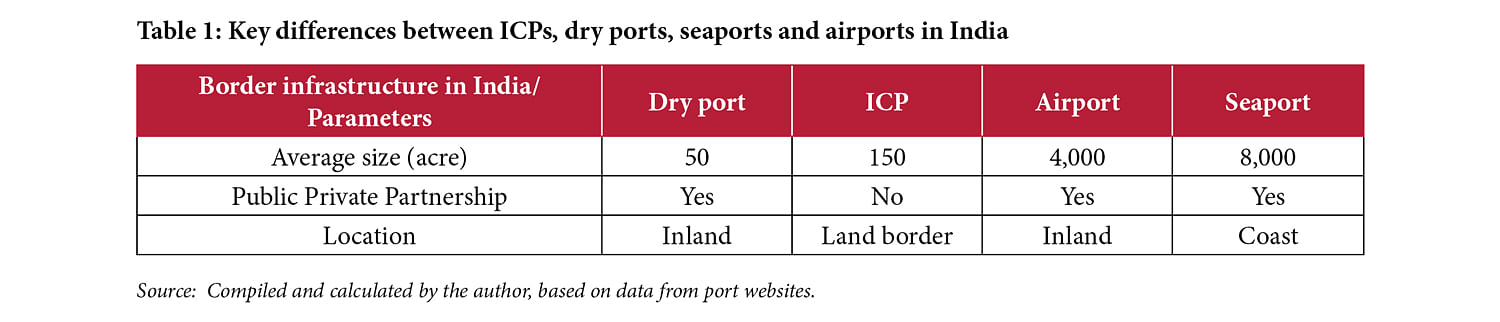

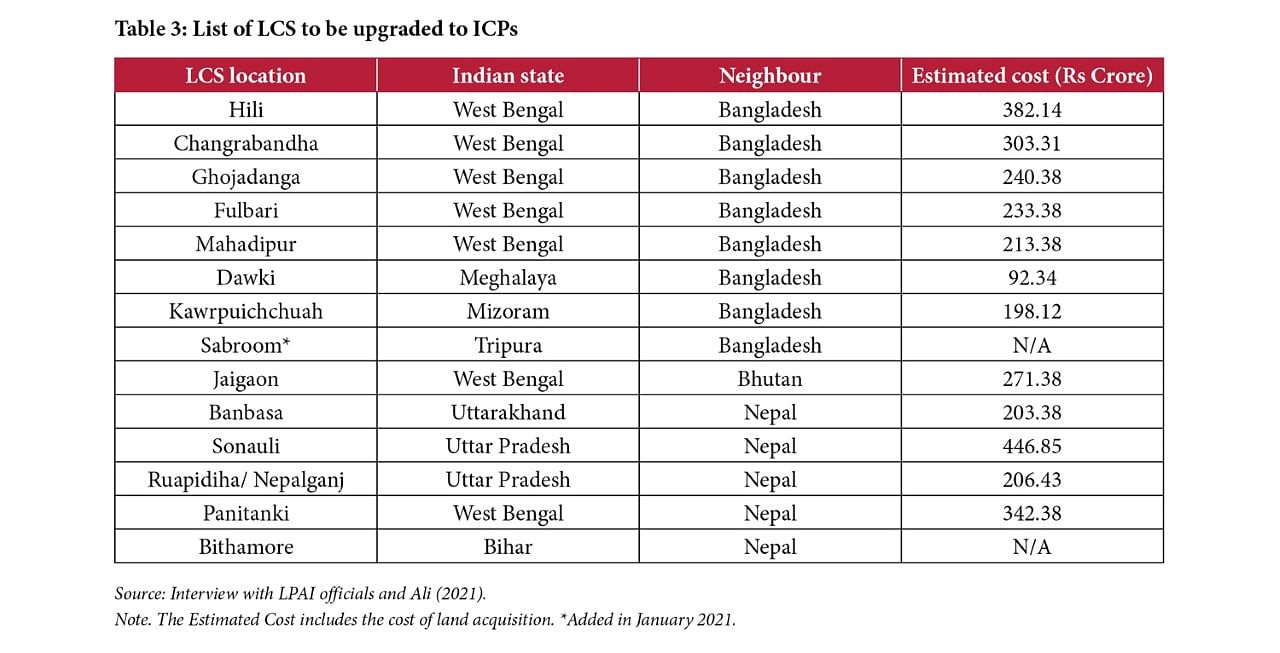

Compared to seaports and airports, the ICPs are relatively smaller ports built at a cost up to Rs 200 crore (approx. US$ 29 million). Table 1 compares the size, management, and location of different types of ports in India. In June 2006, the Additional Secretary (Commerce) had identified 13 LCS to be upgraded to ICPs at an inter-ministerial meeting based on the volume of trade. Of these, six have been completed and inaugurated (Table 2; Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Home Affairs [PSCHA], 2010).

In 2018–19, the government decided to do away with the phase-wise development of ICPs and instead prioritised development based on freight and passenger volume. According to an official at the LPAI, the goal is to have 23 ICPs on India’s land borders by 2025.

Given that less than 2% of India’s global trade takes place through the ICPs (thereby generating lesser revenue), limited emphasis has been laid on its expansion and further development till recently. In comparison, 70% of India’s trade-by value and 90%-by volume, takes place through seaports built over much larger areas than the ICPs (see Table 1). Trade of mostly high-value-low-volume commodities, such as gold, passes through airports. Compared to India’s global trade, India’s trade with neighbouring countries is in low-value goods.

Also read: To view developments in the neighbourhood simply as ‘pro-China’ or ‘pro-India’ is myopic

The future role of ICPs in South Asia

This infrastructure development along India’s land borders begs two key questions: (i) are ICPs really facilitating freight and passenger movement between India and its neighbours? and (ii) with various regional connectivity infrastructure projects in the pipeline, what role will the ICPs play?

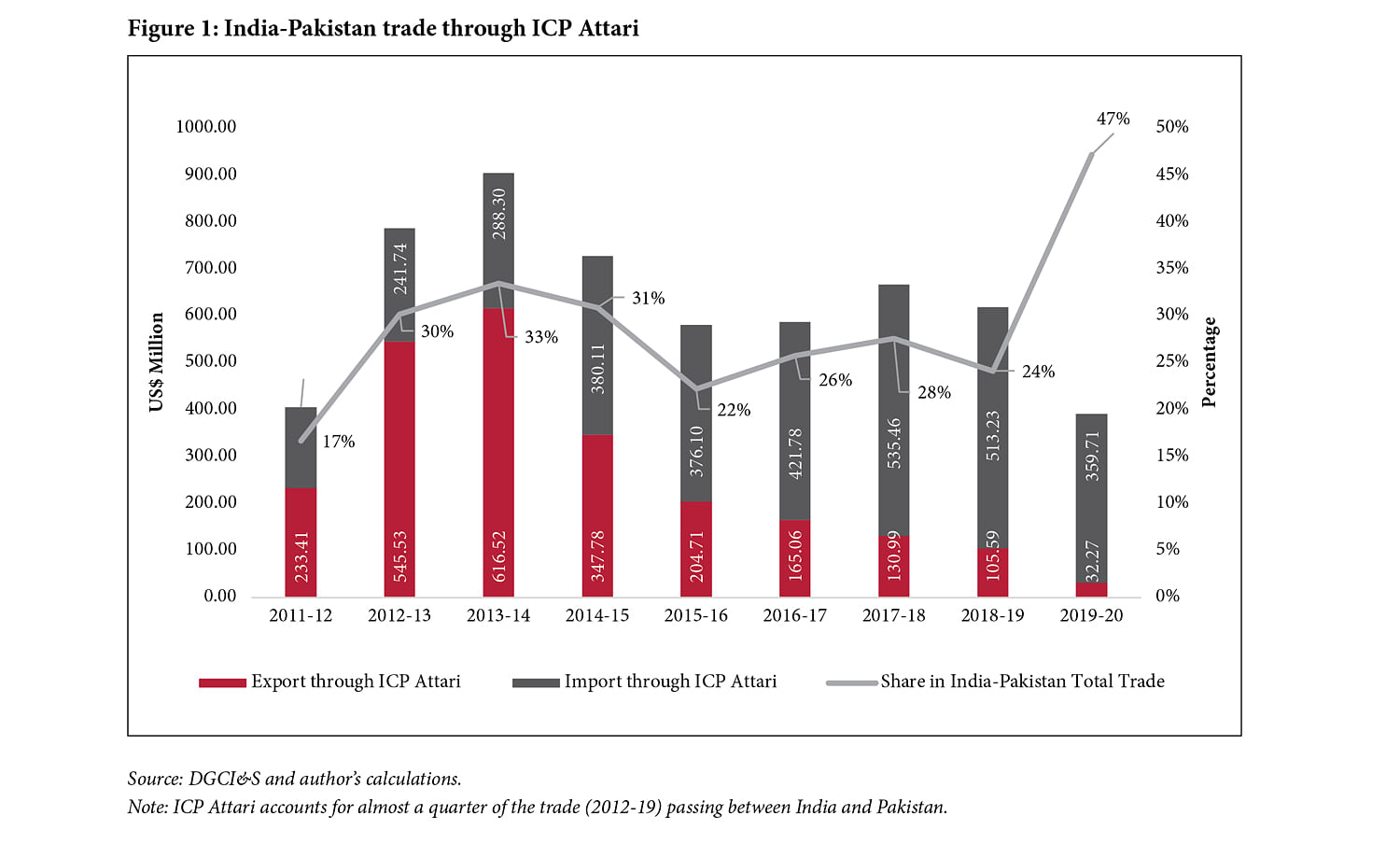

First, an empirical analysis of the various operational ICPs in the region shows an increase in trade and movement of people post the operationalisation of the ICPs. For instance, India’s exports to Nepal increased by 75% post initiation of ICP Raxaul in 2016; the share of ICP Attari in India’s total trade with Pakistan increased from 17% in 2011–12 to 33% in 2013–14, signifying re-routing of trade from sea; and the passenger movement through ICP Moreh increased by approximately 530% in 2018–19.

Most of the current operational ICPs, including Raxaul and Petrapole, are operating at over 100% capacity. Any further increase in volume leads to congestion on the approach roads and within the ICPs. The volume of freight and passenger traffic is soon likely to increase with various connectivity infrastructure initiatives linked to the ICPs coming to fruition. Therefore, it is important that a pre-emptive growth estimation be done for traffic through the ICPs, so that adequate facilities can be provided for different types of cargo while maintaining the export clearance time as 24 hours.

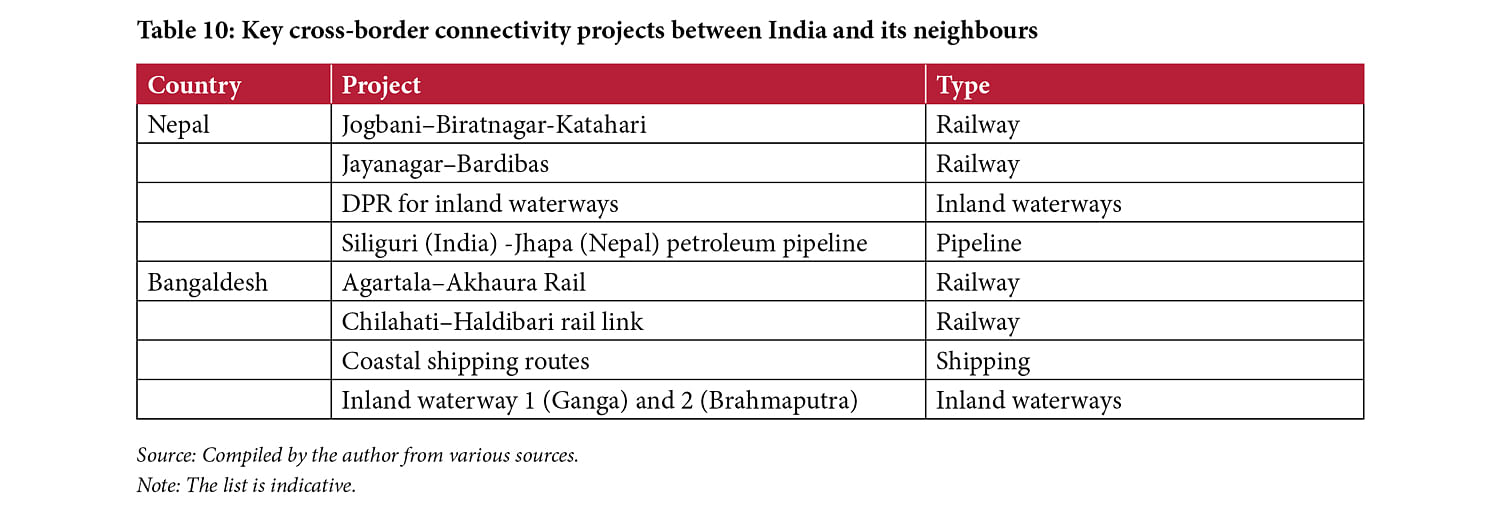

Second, as part of India’s ‘Act East’ and ‘Neighbourhood First’ policies, several regional connectivity initiatives have been taken in South Asia that warrant a reassessment of the role that ICPs would play in trade facilitation and movement of people. These regional connectivity initiatives will increase the mandate of the ICPs. Table 10 below provides a list of key infrastructure projects between India and the neighbouring countries.

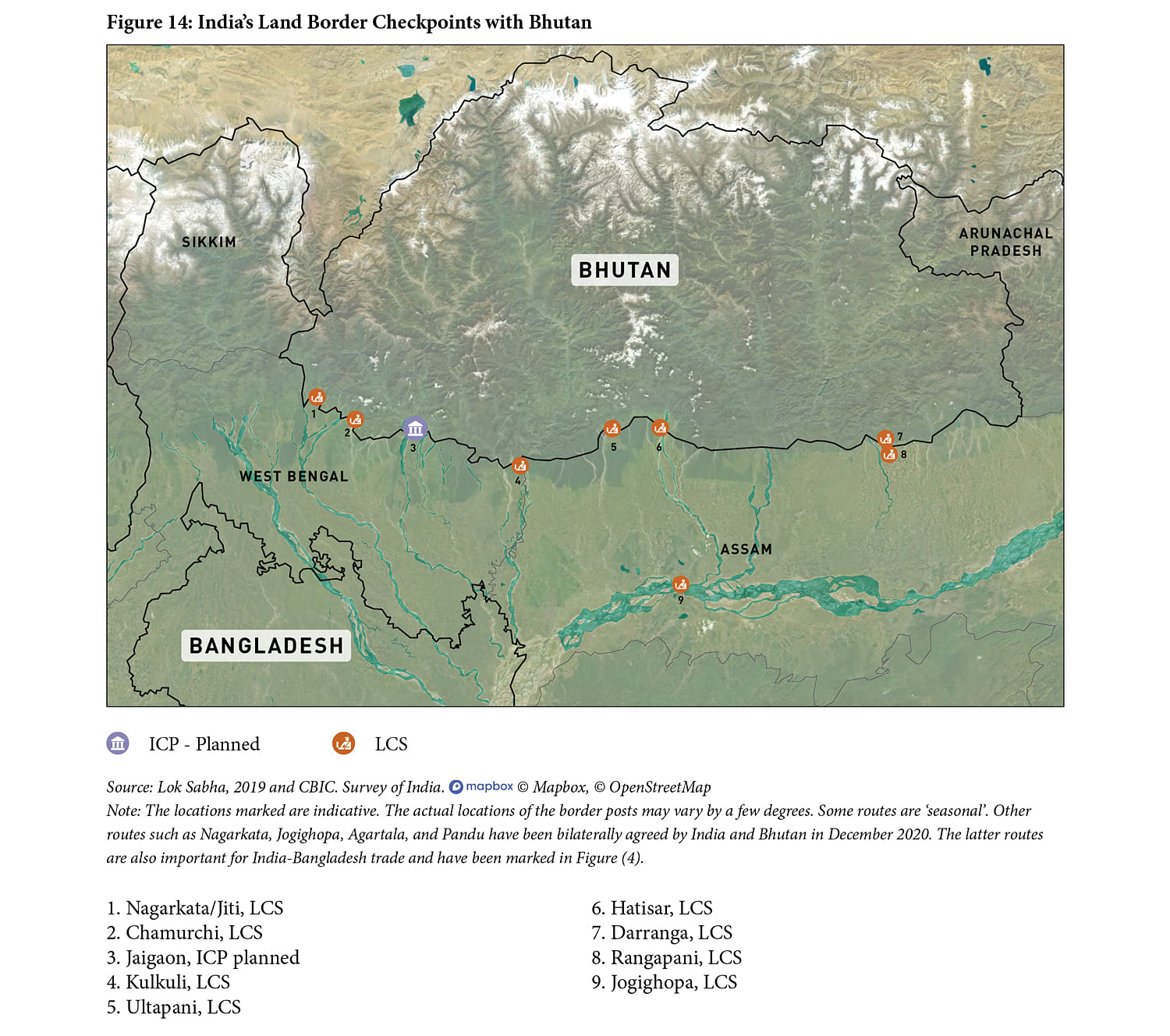

With Nepal, rail connectivity projects such as the Jogbani–Biratnagar and the Jayanagar–Bijalpura–Bardibas railway link are nearing completion. Apart from this, India has also offered assistance in developing inland waterway transport with Nepal. With Bhutan, India inaugurated a new route between Jaigaon (West Bengal) and Ahllay, Pasakha (Bhutan) to decongest vehicular traffic along Jaigaon-Phuentsholing route (Figure 14). In 2020, India opened four more trade routes with Bhutan at Nagarkata, Agartala, Jogighopa, and Pandu. The latter two are riverine ports.

With Bangladesh, four rail lines are now operational. The 12-km-long Agartala–Akhaura railway link is under execution; this route is expected to cut travel time between Tripura and Kolkata via Dhaka and facilitate freight movement from India’s Northeastern states to Kolkata. Inland waterways is another mode that has seen development in recent years. In September 2020, during the pilot test of the Chittagong–Tripura inland waterway route, 50 MT of cement was transported on river Gomti from Daudkandi (Bangladesh) to Sonamura (India) via a 90 km waterway.

Also read: China’s trade with India’s neighbours has grown stronger since 2005. Delhi must catch up

More work remains to be done

According to a former MEA official, the planning for key projects such as roads and ICPs is done on a ‘past-experience’ basis and not a ‘forward-looking’ approach. For instance, he notes that roads are built based on the current traffic volume and not on future projections; and consultants and planners work on old statistics. Given the huge potential of these routes in facilitating multi-modal transportation, it is important that infrastructure be developed at the ICPs keeping future potential in mind, and not on existing trade and transit figures. There is also a need to ensure alignment of the existing border infrastructure, including the ICPs, with the above-mentioned regional connectivity initiatives to accrue maximum benefit for trade facilitation and to ensure the seamless movement of people across sub-regions. Such developments warrant infrastructure upgradation and investment in technology upgradation in the border areas.

Furthermore, at an inter-regional level, ICPs are envisaged to connect the transport of Indian goods to the Northeast region transiting via Bangladesh, and further link them with supply chains in South-East Asia. Several other connectivity initiatives are also at various stages of development connecting South Asia with Southeast Asia, such as the India—Myanmar—Thailand (IMT) Trilateral Highway, Asian Highways 1 and 2, the Trans-Asian railway network, among others. Some of these routes intersect at the ICPs. For instance, the IMT route passes through ICP Moreh. The infrastructure is expected to play a key role in multi-modal transportation in the region and pave way for easing transportation from South Asia to Southeast Asia.

While the need for ICPs arose out of border security concerns, increasing the volume of trade with neighbouring countries as well as connectivity through important infrastructure projects should be the driving factor behind selection of the LCSs for upgradation to ICPs. The construction of ICPs has shown significant improvements at certain places, however, not much improvement has taken place at other border points due to lack of a mirror infrastructure in the neighbouring countries. For instance, the case of ICP Petrapole shows that the increase in freight traffic has been limited due to various infrastructural deficits, such as the lack of adequate parking and warehousing space at the corresponding land port in Benapole, Bangladesh.

Apart from this, several common challenges exist across the ICPs, including harmonisation of working hours with neighbouring countries, limitations in truck movement, absence of partner government agencies such as plant and animal quarantine, and paucity of warehousing space. These challenges will need to be addressed for further construction of the ICPs, in order to promote seamless regional trade and logistics.

Riya Sinha is a Research Associate at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, New Delhi. She tweets @_RiyaSinha. Views are personal.

This is an edited excerpt from the author’s working paper ‘Linking Land Borders: India’s Integrated Check Posts‘, first published by the Centre for Social and Economic Progress.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)