Ask any small Indian firm how long it takes to get paid by larger companies, what kind of a runaround they’re given, what devilish excuses they encounter on the way, and you’ll wonder how they remain in business.

The answer is simple: They raise cash by borrowing against the value of property.

Such advances are tailor-made for the entrepreneur. A term loan for business expansion sometimes comes bundled with a working capital limit, all of it backed by the entrepreneur’s residential or commercial property, preferably self-occupied and in a big city.

Conceptually, there’s nothing wrong here. Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto’s key insight was that poor countries become rich when their toiling masses have clean, marketable titles to property they can mortgage to start businesses.

Also read: Modi govt’s MUDRA is feeding dreams of your local beautician, grocer… and bad loans

The problem with the Indian loan against property is more to do with the lenders than the borrowers. Like with most credit creation in India in the past few years, banks have ceded space even here to nonbank, or shadow, lenders.

Shadow lenders got cheap funds from wholesale markets, including mutual funds. They gave credit to small businessmen who then refinanced their loans even more cheaply by going to another shadow lender. (I noted in January 2017 that yields on loans against property had fallen by 300 basis points in just 12 to 18 months.)

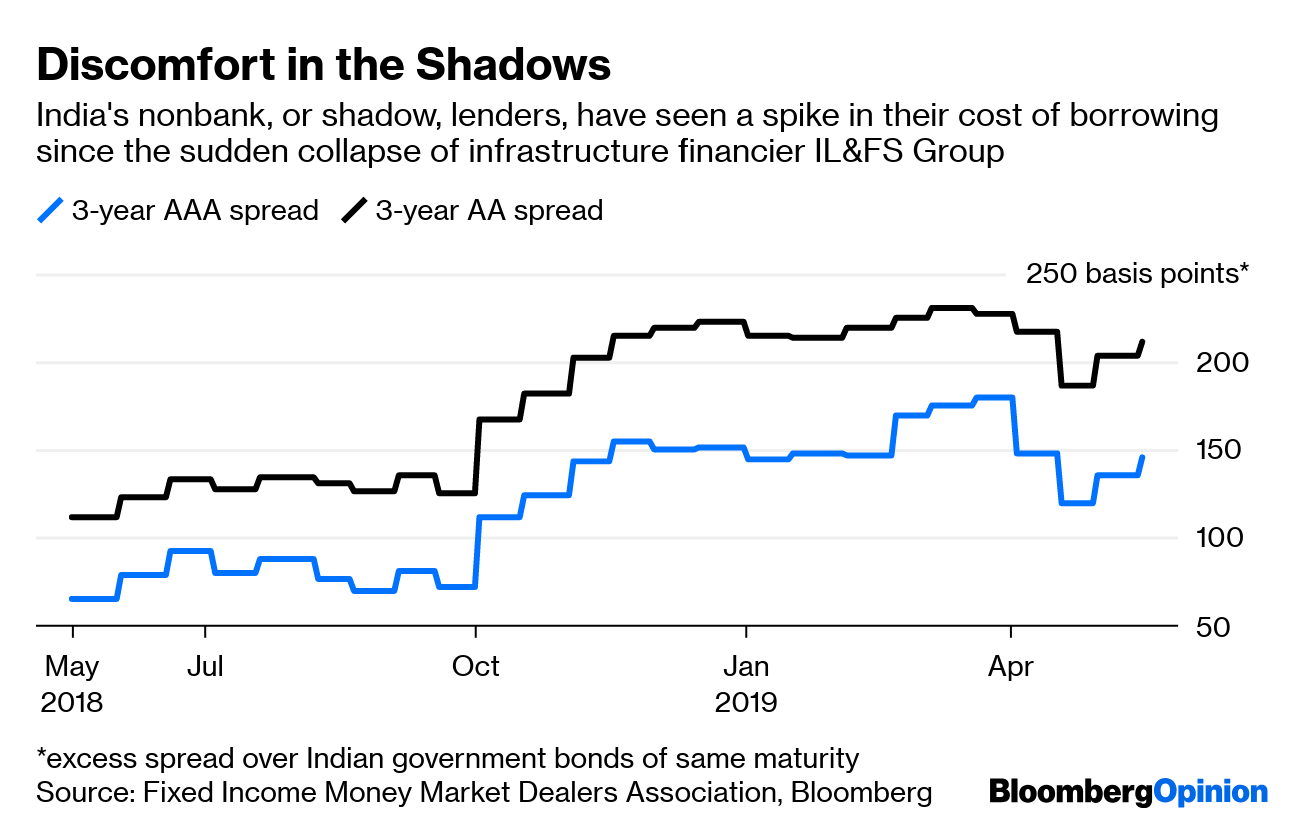

Trouble started when the sudden bankruptcy last year of infrastructure financier-operator IL&FS Group triggered a crisis of confidence and raised funding costs for India’s shadow lenders. Since then, the ultimate borrower has been hit by a triple whammy of higher interest rates, fewer refinancing options, and a souring of sentiment among lenders about the collateral. Real-estate valuations are under stress because developers, which themselves need large dollops of refinancing, aren’t getting any.

Trouble started when the sudden bankruptcy last year of infrastructure financier-operator IL&FS Group triggered a crisis of confidence and raised funding costs for India’s shadow lenders. Since then, the ultimate borrower has been hit by a triple whammy of higher interest rates, fewer refinancing options, and a souring of sentiment among lenders about the collateral. Real-estate valuations are under stress because developers, which themselves need large dollops of refinancing, aren’t getting any.

It used to be that entrepreneurs would take out loans for 10 years to 15 years against property and refinance them in three to five. Now they can’t, so defaults are rising. India Ratings and Research Pvt, a unit of Fitch Ratings Inc., saw delinquencies beyond 90 days increase to 1.77% in January 2019 from 1.05% in January 2018. If these numbers appear low that’s only because the loans that get turned into securities (and are seen by rating firms) are of higher quality. Riskier borrowers, who pawn their homes to more adventurous lenders, are faring far worse.

Also read: SC ruling on bad loans is a bounty for 70 tycoons with $55 billion outstanding debt

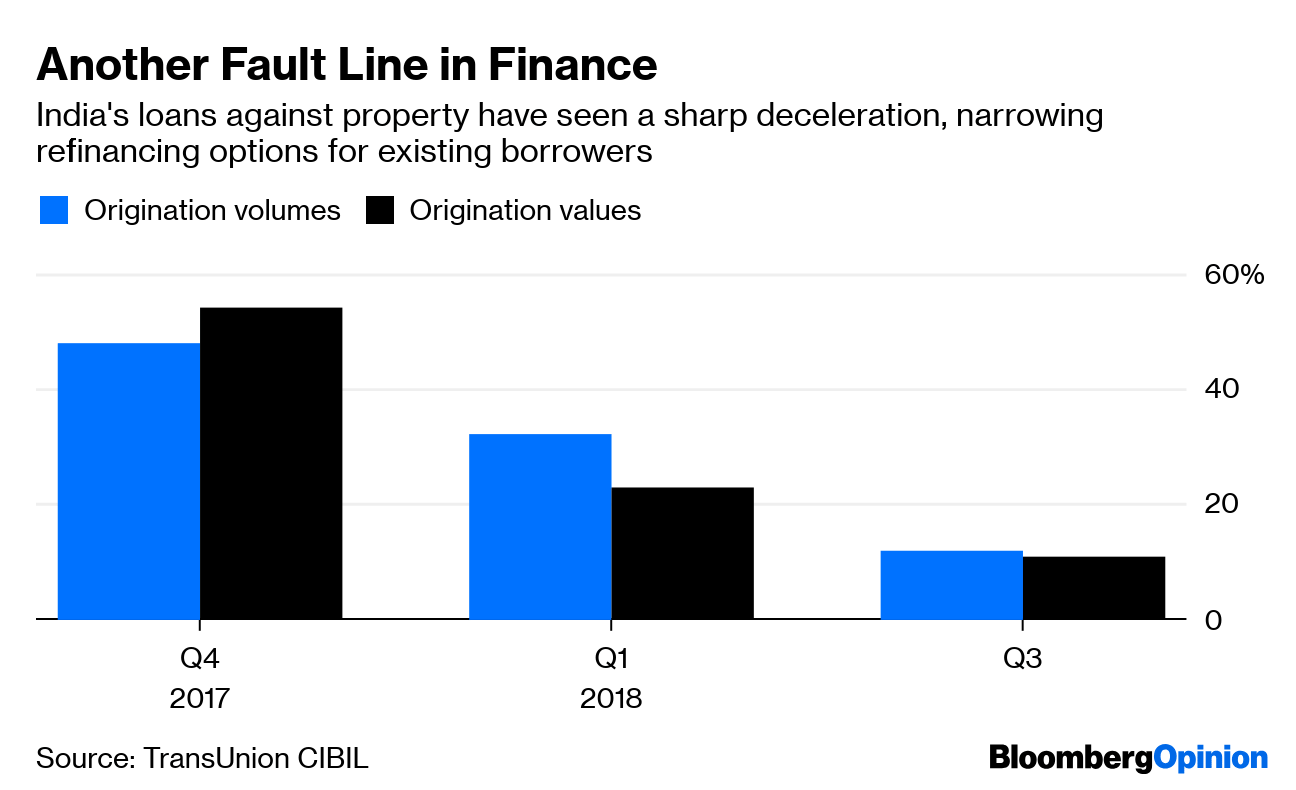

TransUnion CIBIL, a credit registry, put the size of India’s loans-against-property market at the end of last year at 3.84 trillion rupees ($55 billion). However, growth in origination of new loans, in money terms, crashed from 54% in the final quarter of 2017 to to 11% in the three months through September, when IL&FS blew up. It may have fallen further since then. Slower origination means even more defaults in future because stressed borrowers won’t get refinancing so easily.

And borrowers are stressed. Car and SUV sales in India had their worst slump in almost eight years in April. Even soap and biscuit makers are struggling to eke out volumes. These are big, publicly traded companies, whose first response in tough times is to shorten their own working capital cycle by lengthening it for their suppliers – the smaller firms. The response of a government that’s desperate to boost its tax kitty will also be to delay refunds to firms in the supply chain.

A $55 billion source of working capital slipping out of the reach of small firms will trigger a chain reaction. Investors aren’t prepared for it. As India watchers wait for May 23 to see who gets elected as the next prime minister, probably the bigger question is what comes next for finance. Someone will have to fix this broken engine, and quickly.

One facet of a broken economy. It will be difficult to find sectoral solutions in isolation. If soap is not selling as much as it should, HUL is struggling, providing more working capital to its small suppliers is not good enough. Many columns, perhaps a few books as well, will soon be written on how so much sand got chucked into the gearbox of a recovering economy.