Muslim views and opinions on religious discrimination have emerged as one of the most controversial findings of the recent Pew report on religion. A section of commentators argue that this survey does capture the everyday form of Hindutva communalism and its impact on Muslim psyche. The Pew report is juxtaposed with a few experience-based accounts of Muslim individuals to draw a pessimistic conclusion that nothing is left for Muslims in India.

This strange comparison between experience-based individual anecdotes of religious discrimination and the survey findings based on structured questionnaire is extremely misleading. The survey findings offer us a big picture of Muslim presence, while the individual stories and anecdotes introduce us to the complex, everyday Muslim encounters with communalism. Both are valid. It is, thus, necessary to read the macro analysis of Muslim imagination in relation to individual micro level episodes of religious discrimination.

The findings

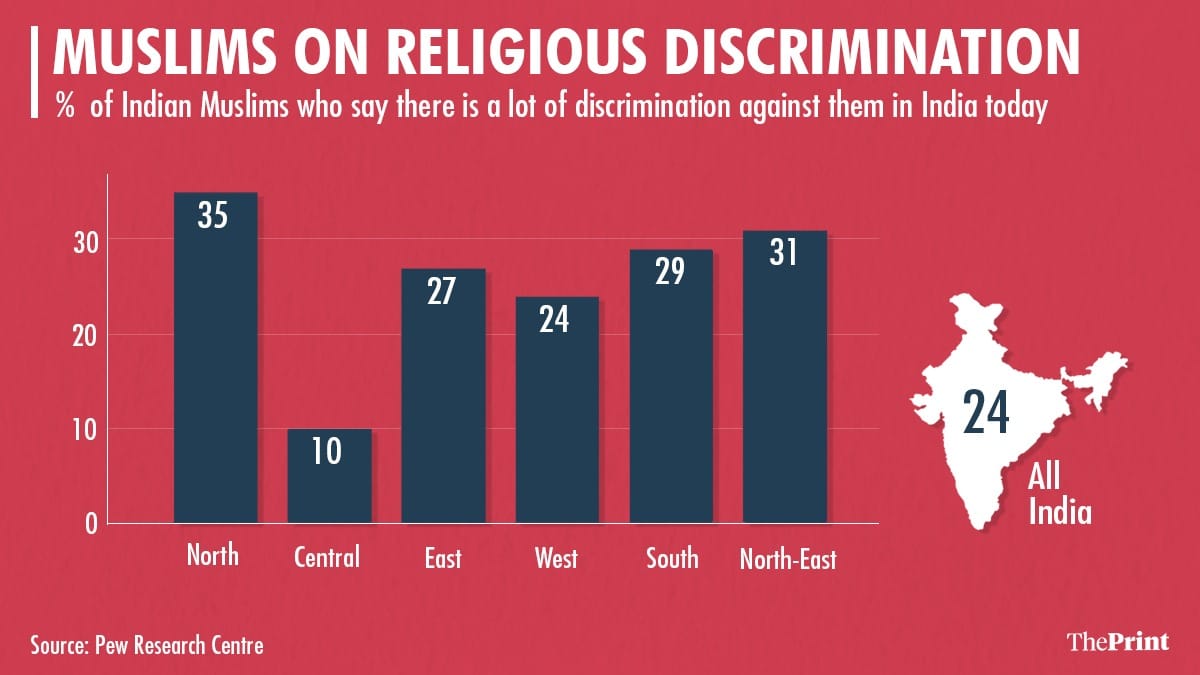

It is important to emphasise that the Pew report offers us a comprehensive and diversified overview of Muslim perceptions. It reveals that 24 per cent Muslims think that there is a lot of discrimination against them in India.

This figure obviously destabilises the commonsensical view. Aggressive Hindutva politics supported by anti-Muslim discourse, run by a certain section of media, has led to many violent episodes. In fact, lynching of innocent Muslim individuals in the name of cow worship has been normalised. It is legitimate for any curious observer of Indian public life to suspect this figure.

The report, however, does not present this finding as a conclusive answer. It unpacks this aggregate Muslim response in relation to regional diversity. This region-wise assessment offers us a very different picture.

Around 35 per cent Muslims in north India claim that they have faced religious discrimination in the last one year. One finds a very similar response in the northeast. Thirty-one per cent Muslims in this region confirm that there is a lot of discrimination against them.

The Muslim response in central and western parts of the country is rather unexpected. These regions have also experienced a lot of communal violence in the past. The situation has only deteriorated in the last few years. Yet, we do not find any overwhelmingly critical Muslim response in these states. Why?

Also read: BJP version of Hindutva is rising but there is one aspect where it failed to convince Hindus

Four aspects of religious discrimination

These findings, I suggest, underline four serious aspects of religious discrimination in contemporary India.

First, the violent anti-Muslim Hindutva politics is a north-centric phenomenon. Although various reflections of this politics can be found in other parts of the country, the Babri Masjid dispute, Shah Bano episode, love-jihad campaign, and the aggressive cow protection movement provide a contextual specificity to violent Hindutva in the north.

This might be the reason why a sizeable number of Muslims in north India feel that they face serious religious discrimination. Journalist Mohammad Ali’s recently published essay confirms this finding. This may also be true about the east and the northeast regions. The rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Assam and West Bengal and the CAA protests seem to influence Muslim opinion in the northeast.

Second, this regional variation also demonstrates a very serious fact of our public life. The anti-Muslim discourse has now been normalised. We must remember that lynching of innocent Muslims or attacks on mosques and other Muslim religious places of worship, even during the time of pandemic, are the violent outcomes of a sustained multidimensional anti-Muslim narrative.

This narrative has become a part of our everyday life. Making communal remarks on Muslim individuals in public and spreading hate on social media are no longer seen as unusual or abnormal. This wide-spread normalisation of Muslim bashing also influences Muslim opinions and perceptions.

This explains the nature of Muslim response on religious discrimination in central and western India. It seems that Muslims, especially in these regions, do not think that communal slurs like katwa (circumcised), mulla/mulli, miya, Jihadi, Pakistani can also be seen as ‘religious discrimination’.

Third, the overall Muslim reaction to various facets of religious discrimination also point towards a failure of violent Hindu essentialism. The act of lynching and its wider dissemination through popular media (WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube) is guided by two related impulses.

It aims to mobilise a community of anti-Muslim ‘warriors’ (the lumpen elements) in the name of Hindutva. At the same time, there is a wider objective to create terror and fear in the minds of Muslims. The Pew survey shows that violent Hindu politics has not yet succeeded in terrorising the Muslim mind.

This brings us to the fourth aspect of religious discrimination. Poor, marginalised, unemployed Muslims, it appears, have realised that anti-Muslim Hindutva has emerged as the dominant narrative of Indian public life. This realisation encourages them to work out various survival strategies.

They do not have any opportunity to take refuge in New York, Washington, London, Vienna or Berlin for the protection of what is called ‘human rights’. Nor do they survive with the stigmatised identity of a victim community. They are bound to live in their immediate surroundings without giving up their Muslim identity.

ThePrint’s reporter Fatima Khan’s engaging report on Muslim aspirations is relevant to underline this point. Based on her extensive fieldwork, she argues that there is strong inclination among Muslims in different parts of the country to constructively engage with the political system.

The Pew findings, in fact, reiterate this Muslim resolve.

(The Pew study is a comprehensive in-depth exploration of India’s contemporary religious life. The report is based on interview of 29,999 Indian adults (including 22,975 who identify as Hindu, 3,336 who identify as Muslim, 1,782 who identify as Sikh, 1,011 who identify as Christian, 719 who identify as Buddhist, 109 who identify as Jain and 67 who identify as belonging to another religion or as religiously unaffiliated). Interviews for this nationally representative survey were conducted face-to-face from November 2019, to March 23, 2020. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into 16 languages, independently verified by professional linguists with native proficiency in regional dialects. For full report, click here)

This article is part of a series on the latest Pew Survey on religion in India. Read all articles here.

Hilal Ahmed is Associate Professor at CSDS. He was one of the expert advisors for this study. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)