India’s agricultural yields are abysmal. The country farms far too much land area and produces far too little grain output, with way too many people dependent on this inefficient operation. It’s a trap of poverty that destroys the environment as collateral damage. And if one takes BR Ambedkar’s social critique into consideration, it does all this while breeding a culture of casteism, in turn making the village a cesspool.

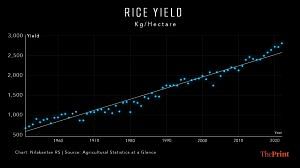

Consider rice. Despite the narrative of a green revolution in the 1970s that all of us were raised on, the data hardly reveals one. India has had very poor yields in its most widely raised crop. On the face of it, rice yield per kg hectare has risen from 688 in 1950-51 to 2809 in 2021-22, but the world’s average yield is almost twice that. Forget the best; India’s yields aren’t even close to the global average. This average includes much of Africa, where yields are considered very poor. And this is after a generation of ‘Green Revolution’ in this country.

More spending, less returns

Governments in India – both Union and state – have a problem on their hands. They spend a significant amount on agriculture and allied activities with very little returns. For example, the Indian government’s projected expenditure on agriculture and farmer welfare in 2023-24 stands at Rs 1.25 Lakh Crore, with an additional Rs 1.75 Lakh Crore allocation for fertilisers, and more than Rs 10,000 crore on food processing, animal husbandry, fisheries etc. More funds have been allocated to the water resources department under the Jal Shakti ministry, which is, of course, also linked to irrigation and agriculture. Together, this sum is greater than the Union government spends on health and education and many social development sectors combined.

Agriculture, over and above being a significant source of spending in the Union budget, is a state subject as well. State governments, put together, likely spend more than the Union. Which makes one ask: with an estimated Rs 7 Lakh Crore spending in one year between the states and Union, what are we getting? Why are the yields so poor that we don’t even match the global average?

The answer, when one looks at the line items of spending, becomes clear: there is hardly any spending on agriculture itself, which would ideally mean spending on research and other ways of improving future yields. Instead, it’s largely spending on farmers to keep them where they are. An example of that is the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-Kisan), which is essentially a version of basic income, except it’s targeted at farmers. The question that ordinary people who aren’t farmers are entitled to ask at this point is: why not make this generic instead of targeting farmers? Maybe the return on that investment will be higher?

If the linear trend line and the average absolute yield for rice are used as an indicator, which is fair given most other crops have a similar trend, it’s clear that the spending on agriculture is not yielding the desired return. Those people who aren’t farmers and seeking equality will have a point if we compare this return on investment in other areas, such as education.

Also read: India could have sailed August rain deficit but MGNREGS failing in water conservation

PM Kisan-type solutions are ineffective

India’s agriculture expenditure being a subsidy for farmers also means it is a subsidy for land-owning farmers for the most part. That again worsens the existing inequality in society. Why a landowner should get the PM-Kisan subsidy at the expense of the landless labourer is another fair question to ask. The government has tried to address that in recent times, but that hasn’t made a dent. This is why a direct benefit transfer programme, which is social spending in reality but somehow seen through the prism of agriculture, is problematic.

A simpler, just and more effective solution will be for states to decide the social aspects of policy while the Union focuses on research and longer-term solutions that will result in higher yields over time. A single PM Kisan-type solution across different states is unfair and ineffective by design. Whereas even a single rice variety that is likely resistant to climate change volatility will truly help stabilise yields in the future. There is value in centralising some aspects of policy.

Research is a prime example. There is absolutely no value in paying a relatively rich farmer in Punjab, who already owns land with high yields, an additional Rs 2,000 each quarter.

Until the time India meets and exceeds at least the global average in terms of yields, this spending on agriculture is far worse than any freebie that fiscal conservatives like to critique. At least free public transport has some social value. A subsidy on agriculture that incentivises the existing methods of farming has none.

Nilakantan RS is a data scientist and the author of South vs North: India’s Great Divide. He tweets @puram_politics. Views are personal.