Addressing the global business elite at the 2018 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi placed India firmly in the camp of globalization and free trade. Echoing a speech delivered by Chinese President Xi Jinping at the same forum a year earlier, Modi suggested that India could be a standard-bearer for globalization and provide global leadership for trade liberalization. Touting the “radical liberalization” of the country’s foreign direct investment (FDI) regulations, Modi had boasted in 2016 that India was “the most open economy in the world for FDI.”

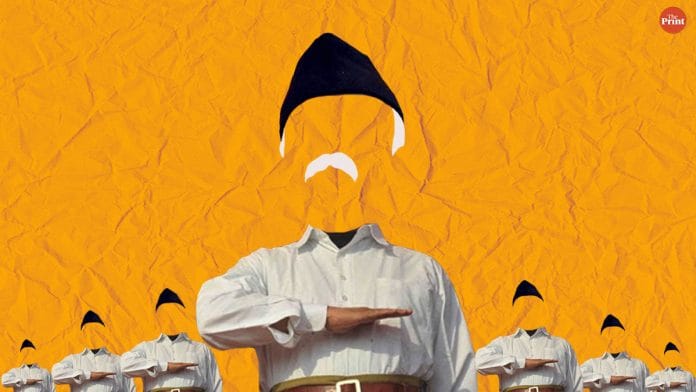

But not all members of the Sangh Parivar—the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its affiliate organizations, of which Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is one—shared the prime minister’s enthusiasm for foreign investment. The Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM), an economic affiliate of the historically protectionist RSS, vehemently opposed liberal FDI norms, arguing that “FDI has done more bad than good to the economy.”…

The Sangh’s protectionist reputation notwithstanding, the leadership of the RSS… has been content to let multiple points of view coexist, preferring to mediate the policy differences among the BJP and the RSS’s economic affiliates on a case-by-case basis.

The BJP started as a political party with autarkic instincts, supporting foreign investment only in high-tech sectors, a stance illustrated by the pithy slogan “computer chips but not potato chips.” Over time, particularly during the tenure of former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the party began to favor liberal economic polices—best exemplified by its decision to abandon a long-standing ideological totem to propose foreign investment in retail. The selection of the business-friendly Modi… suggested that the BJP was evolving into a more conventionally center-right political party, and that the party was moving away from the statist and autarkic proclivities of the Sangh.

The RSS’s own economic ideology, which has often been caricatured as “communism plus cow,” has also evolved. While the RSS has softened its once implacable opposition to globalization and economic liberalization, its current economic philosophy is best summed up as populism with Indian characteristics.

Also read: The so-called non-political RSS is setting the agenda for 2019 elections

But political exigencies… and pressure from the Sangh has helped push the BJP government’s economic policies in a more populist direction, especially in the last two years of its tenure. The increased convergence between the Sangh’s economic populism and the government’s own policies…led the BJP to dilute, deemphasize, or even abandon some of its more market-friendly campaign promises.

Still, the influence of the Sangh on the BJP is not unidirectional. In many cases, Sangh affiliates certainly do shape government policy. In other instances, the BJP government itself has influenced the thinking of its fellow travelers within the Sangh, bringing them closer to its point of view… Irrespective of the direction in which this causality appears to run, there has been a noticeable policy convergence between the BJP and the Sangh on many economic matters. This convergence is not only shaping the BJP’s 2019 election campaign, but it will also likely define a putative second term for the BJP if the party returns to power.

BJP’s Economic Evolution

The evolution of the RSS’s economic philosophy was mirrored by its political affiliate, the BJP. For much of the post-liberalization era, the BJP’s swadeshi wing was more prominent… Much like the RSS, the BJP also supported decentralized production and an economic policy that tilts the playing field toward family-owned small businesses.

The BJP’s swadeshi wing was gradually sidelined during the tenure of previous BJP prime minister Vajpayee… Much to the dismay of some within the Sangh Parivar, the Vajpayee government opened up sectors such as insurance and media to foreign investment and privatized state-owned enterprises. Expressing his ire, (Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh’s Dattopant) Thengadi called Yashwant Sinha, who was then serving as finance minister, a “criminal” and labeled his policies “anti-national.”

When serving in an opposition role, however, the BJP has opportunistically decried further economic liberalization—such as when it objected to the Congress Party’s proposed opening of the retail sector to foreign investment. The dynamic shifted once more with the BJP’s decision to choose the business-friendly Modi as its candidate for prime minister, which further marginalized the party’s swadeshi wing.

Also read: The ‘Bahujan unity’ model is the only way to counter the BJP-RSS at national level

More recently, as the 2019 general election has approached, political expediency as well as pressure from the Sangh have shifted the government’s policies in a more populist direction in some cases.

Over the past year, the RSS has leveraged India’s changing political context to nudge the BJP government in a more economically populist direction, although these efforts have not been unambiguously successful. In many cases, government policy bears the RSS’s imprint, but these positions have not always been incorporated into the final drafts of legislation or fully implemented. Furthermore, this pattern of influence on economic thinking runs both ways: just as the RSS and Sangh affiliates have helped shape government policy, the BJP too has exerted influence on its Sangh colleagues. While the causal connections are messy—and circular—there is no doubt that the RSS has found a seat at the policy high table for the last five years.

A prominent recent instance of this pattern is the nomination of the SJM’s S. Gurumurthy as a director on the central board of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The RBI board has a limited role in policy decisions and has traditionally served as an advisory body. However, Gurumurthy lobbied the RBI to change regulations that he perceived were choking the flow of credit to small and medium enterprises.

The SJM and other RSS economic affiliates have also supported the repatriation of RBI “excess reserves” to the government, resources that could presumably be used to fund populist welfare measures in the run-up to the 2019 election. The SJM noted in its newsletter that “only [the] central government owns the right over these reserves and profits of the RBI.” The ensuing controversy led RBI governor Urjit Patel to quit his position months before the end of his term, further damaging the government’s reformist credentials. Among the first decisions of the new governor, Shaktikanta Das, was to allow regulatory forbearance on the restructuring of the overdue loans of small and medium enterprises—a marked reversal of the previous RBI governor’s policy against the restructuring of loans.

The Indian government has pursued more populist economic policies on other fronts as well. A month after Modi’s celebrated 2018 Davos speech, Union Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced in his budget speech a “calibrated departure from the underling policy [of reducing customs duty of the] last two decades.” In response to the depreciation of the Indian rupee, caused largely by a bout of financial market volatility that has increased investors’ risk aversion toward emerging markets, the government further selectively increased import duties, ostensibly to reduce the trade deficit…

Also read: Happy that budget has taken our concerns into account: RSS affiliates

More recently, the proposed tightening of norms—a policy that was met with approbation from the SJM—for e-commerce retailers, which hampers the operations of Amazon and Flipkart, flies in the face of the prime minister’s promise of a “red carpet” for foreign investors. The increased assertiveness of the Sangh Parivar also caused the government to abandon the prime minister’s campaign claim that “the government has no business being in business,” instantiated most recently by the scrapped plans to privatize perennially loss-making Air India.

Notwithstanding the Indian finance minister’s repeated commitments to fiscal prudence, and in the face of flagging revenues from the newly introduced GST, the Modi government has also proposed an expensive expansion of the welfare state. Ayushman Bharat (better known as Modicare) seeks to provide health insurance of 500,000 rupees (approximately $7,000 or more than three-and-a-half times India’s per capita GDP) to the poorest half of Indian citizens. Similarly, in a decision that reflects skepticism over the efficacy of farm loan waivers from quarters within the Sangh, the Modi government announced an income support scheme for farmers in the 2019 budget to ameliorate the sagging fortunes of the agriculture sector…

Much to the chagrin of the party’s libertarian-minded supporters, the BJP’s 2019 manifesto and campaign platform will likely center on an expansion of public spending and a deemphasis on business-friendly appeals. The BJP’s 2014 campaign was centered on the promise to bring acche din (better days) to the Indian economy; the next campaign is poised to be more preoccupied with promises of expanding the welfare state and improving the efficacy of welfare delivery.

The RSS, for its part, appears content with the policy direction the Modi government has taken, and this shift could not have come at a better time: the RSS cadres are an important source of help for powering the BJP’s formidable election machine. A satisfied, energized cadre will provide a much-needed lift to the ruling party’s reelection prospects.

Gautam Mehta is a recent graduate of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). He helped write a book on the Sangh Parivar, co-authored by Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle, called The RSS: A View to the Inside (Penguin Random House India, 2018).

This is an edited excerpt from the essay ‘Hindu Nationalism and the BJP’s Economic Record’ first published by Carnegie Endowment For International Peace as part of its report titled ‘The BJP in Power: Indian Democracy and Religious Nationalism’.

If the RSS would like the BJP to rule India for the next fifty years, it should get the economic cocktail right. Mrs Gandhi’s nimbu pani will not cut the mustard, to mangle the metaphors.