The story of renaming begins with the namkaran of India itself after Independence.

The debate around the recent renaming of cities such as Allahabad, Faizabad, and Mughalsarai in Uttar Pradesh must go beyond the emotionally charged statements about collective memory, fears of Hindu Rashtra, Hindu pride, and national honour. It signifies a very specific political trajectory.

There are two important reasons why the existing narrative scaffold for this debate must change to illustrate the political nuances at play here.

First, there is a post-1947 history of renaming of cities, places and objects, which must be taken into consideration to have a meaningful discussion on the present moment of name changing. Second, renaming of cities and objects is not merely an ideological issue, it also has a deep political impulse.

Also read: UP government approves renaming of Faizabad as Ayodhya and Allahabad as Prayagraj

India as Bharat

The story of renaming began with the namkaran of this country itself. British India was popularly known as Hindustan. However, the members of the constituent assembly were not fully satisfied with this name.

On 15 November 1948, Shibban Lal Saksena moved an amendment in the Assembly arguing that future India must be called Bharat. This was seconded by Maulana Hasrat Mohani.

This led to a serious discussion on the merits and demerits of renaming of the republic.

It was strongly asserted that Bharat was an originally Indian name. Unlike India and/or Hindustan, it was a native expression to indicate a particular territory.

On the contrary, a section of constituent assembly members, including B.R. Ambedkar, argued that India was the internationally known name of the country, which did not relate to any particular religion. Hence, India should be preferred.

Finally, both India and Bharat were officially selected. That is why Article 1 of the Constitution says: “India, that is Bharat shall be a Union of the States!”

It was a middle-path between the emphasis on our roots and our global projection, or between the ancient civilisation and the new nation-state.

Norms of renaming

This serious and logical discussion paved the way for a few unwritten policy norms for naming-renaming in Independent India, especially in the 1950s.

Former PM Jawaharlal Nehru’s letters suggest he was against the naming of cities and roads after national heroes. In a public statement in relation to Mahatma Gandhi’s statues, he says:

“All over India, there is a tendency to name roads, squares, and public buildings after Gandhiji. This is a very cheap form of memorial…Almost, it seems to me that this is exploiting his name…even more undesirable is to change the famous and historical names which have had a distinction of their own. …Only confusion will result as well as a certain drab uniformity. Most of us will live in Gandhi Roads, Gandhi Nagars or Gandhigrams.”

(Official Statement, The Hindu, 26 February 1948)

To accommodate the historicity of old names with his project of national reconstruction, Nehru spelt out a policy on colonial memorials and statues, which as matter of fact, also underlined his position on naming and renaming of cities and objects.

In a letter to home minister Govind Vallabh Pant on 13 May 1957, Nehru wrote:

‘…Statues can be put in various groups:

1. Those that have some historical importance.

2. Those that have artistic importance.

3. Those which have neither historical nor artistic importance, and

4. Those, which are offensive to Indian sentiments.

In course of last few years, we had, in fact, removed a number of old statues …but we were anxious to do this without any fuss and without creating any international ill will…I suggest that we might give consideration to this last group of statue… In particular, this matter might be looked at from the point of view of the rising of 1857.’

(SWJN, Vol.38)

These carefully articulated responses introduce us to two unwritten norms of Nehru’s policy on renaming.

First, the renaming should not be person-centric; instead, it should reflect a process/event/everydayness of life. Second, the historically evolved names and objects must be given adequate consideration before arriving at any particular conclusion about them.

Nehru tried to adhere to these norms. Perhaps that was the reason why he could not find any problem in naming his dream city Chandigarh — a name with a strong religious undertone.

Also read: Narendra Modi is a name-changer, not a game-changer: Shashi Tharoor

Politics of renaming

The post-Nehru political class started disregarding these norms almost immediately after Nehru’s deaths. Many Gandhinagars and Nehrunagars came into existence in the country and renaming became a tool to carve out space in collective official memory of the nation.

Three aspects of this politics can be underlined.

First, political parties use naming and renaming of places to mark their distinct political identity. This is not entirely a symbolic exercise. The naming and renaming is used to provide a standardised identity to communities that constitute the core constituency of voters. Mayawati’s move to rename districts after Dalit icons is no different from Adityanath on Faizabad and Allahabad.

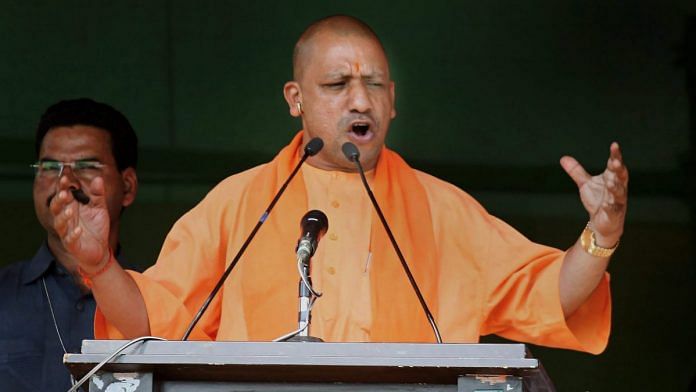

Second, the renaming of the places and objects has become an expression of majoritarianism. Such decisions are taken by the executive elite without any legislative deliberations or public discussions. Adityanath argues:

“We did what we felt was good. We renamed Mughalsarai as Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhayay Nagar, Allahabad as Prayagraj and Faizabad as Ayodhya. Where there is a need, the government will take the steps required.”

Political imagination of history

The placing of history in the naming-renaming business is the third aspect of this politics. The political elite construct favourable and convenient imaginations of the past, which do not necessarily correspond to the actual historical accounts of events and places. Although it has become an established norm of Indian politics, the BJP’s politics of the past is extremely unique and influential.

In this case, the past is not seen as an evidence of historical events or persons; rather, it is invoked to justify a few politically constructed propositions, which are posed as assertions of faith. The Babri Masjid becomes the birthplace of Lord Ram and Allahabad becomes Prayagraj —primarily because Hindu believe in it.

Also read: It makes good politics for Amit Shah to defy Supreme Court on Sabarimala, Ayodhya and NRC

This “faith-based past” has helped the BJP to defeat the “evidence-based secular history” in the Ayodhya case.

It is, therefore, absolutely useless to expect that Adityanath would read the secular history of Allahabad before renaming it. He has his own meanings of the place, which stem from BJP’s political mythology.

Hilal Ahmed is an associate professor, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies.

You must not compare Mayawati renaming with Yogi Adityanath’s. Prayagraj and Ayodhya are historical names and are given for due credit.

I agree.

The article is quite insightful.